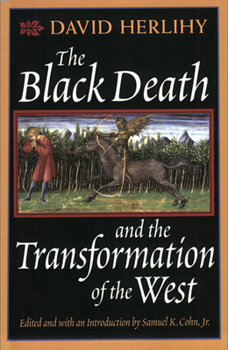

The Black Death and the Transformation of the West

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The Black Death in Europe, from its arrival in 1347-52 through successive waves into the early modern period, has been seriously misunderstood. It is clear from the compelling evidence presented in... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0674076133

ISBN13:9780674076136

Release Date:September 1997

Publisher:Harvard University Press

Length:128 Pages

Weight:0.40 lbs.

Dimensions:0.4" x 5.7" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Short but provacative

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

David Herlihy's revisionist work, The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, would have inevitably been cached away and forgotten; a fate that most miscellaneous intellectual writings face when their authors pass away. Luckily for historians, Herlihy's work, consisting of three unpublished essays about the Black Death, has survived intact and in many ways has been improved upon by Professor Samuel K. Cohn's authoritative analysis. As Cohn's extremely helpful, albeit critical introduction explains, Herlihy's perception of the Black Death and its direct effect on the development of Western civilization was shaped by the ever-shifting environment of modern intellectual thought and his own personal observations. In this, Herlihy's The Black Death and the Transformation of the West, reflects the historiographical truth that was captured by a fellow medievalist: "the knowledge of the present bears even more immediately upon the understanding of the past." (Bloch, 45) During the 1960's, Herlihy's conclusions regarding the Black Death implemented a "modified Malthusian framework," that mirrored Marxist interpretations of the Middle Ages (Herlihy, 2). However, 20 years later, his own observations of modern diseases and, more specifically, modern society's attitude towards the sick, changed his historical perspective on the Black Death. The growth of the AIDS pandemic during the 1980's, a disease that defied socio-economic boundaries, and also, like the Black Death, defied an exact origin, shaped Herlihy's historical interpretation of medieval epidemics. The fact that the "mysterious" origin of AIDS could not be accurately "pinned" to class structure, or a broad Malthusian model, forced Herlihy to question the accepted biological and historical interpretations of the Black Plague (Herlihy, 5) As Cohn argues, AIDS proved to Herlihy that a disease can mysteriously develop and spread uncontrollably throughout the world. Herlihy's first essay provides a fascinating analysis of the historiography of the disease, and even goes as far as to suggest that the Black Death was not caused by the bubonic or pneumatic plague. Herlihy flirts with the controversial theory developed by British Zoologists, Graham Twigg, which states that the plagues that devastated Western Europe were the caused by anthrax. He however, cautions that perhaps "different diseases" worked "synergistically to produce staggering mortalities" (Herlihy, 30). Herlihy opened the door for new ideas. There still remains a heated debate among scholars about what disease or diseases characterize the Black Death. In the latter two essays, Herlihy modifies his initial theory that stated the Black Death was the manifestation of classical Malthusian crises. He instead argues that the miraculous development of the Black Death merely broke what he termed the "Malthusian deadlock", which "paralyzed social movement and improvement" (Herlihy, 38). The short-term economic effect of the

A Few Probelms But Overall A Great Work

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Before his untimely death in 1991 David Herlihy presented three lectures examining the Black Death and in doing so redefined the entire historical outlook on the great plague. These speeches may have been lost, if it were not for Samuel K. Cohn, Jr., who collected Herlihy's lectures and notes and presented them in a concise tome. According to Herlihy although the Black Death had a devastating affected on everything in European society, it kept European culture from getting stale. While historians originally viewed the "great plague" as a disaster that hit Europe and set European society back 100s of years, Herlihy sees the "death" as a liberating force, pushing European society forward, destroying it, but at the same time transforming it, spurring new growth and possibilities. There is a reason according to Herlihy, "that the...characteristics of the population collapse of the late Middle Ages [were] Europe's deepest and also its last." Herlihy's thesis is a simple, yet revolutionary one: that the Black Death created the demand for labor saving devices as the population dwindled, and this in turn pushed European society forward. While most historians approached the subject from a political and military aspect, Herlihy looks at the social effects of the plague on women, art, and society in general, and comes to the conclusion that the plague was, in the long run, a good thing for Europe. The book itself is divided into three major parts reflecting the lectures that Herlihy had delivered at the University of Maine in 1985. Cohn adds an introduction and an extensive section of End Notes, but overly keeps Herlihy's text intact. The first chapter explores the idea that the plague itself may not have been bubonic plague, which is the standard historical theory to this day. "Medical writers of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages," writes Herlihy, "recognized only one type of epidemic disease marked by only one kind of symptom, inflammations, boils, or buboes in the area of the groin, [which] the authority of the ancients may have blinded later witnesses to other symptoms, indicating the presence of other types of epidemic disease." To back up his argument Herlihy knocks down the age-old notion that the plague was spread by infected rats, moving throughout Europe. If, according to Herlihy, the "death" was bubonic, then there should be evidence of an epizootic within the rat population. "To my knowledge," Herlihy states, "not a single Western chronicler notes the occurrence of [such] an epizootic, the massive mortalities of rats, which ought to have preceded and accompanied the human plague." For Herlihy, the disease that ravaged Europe was most likely anthrax. "Anthrax can produce the characteristic swellings which might be mistaken for buboes." The second and third chapters of the book delve into the economic impact of the plague on European society, and how that society rebounded from it. For years historians have look at

Original & thoughtful, but also some unanswered questions...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Herlihy makes the excellent point that the Black Death strengthened Europe in the long run (meaning over many centuries). For centuries, Europe had lagged behind China in technology and standard of living. By the 16th century, Europe was ahead, and has remained so ever since. What made the difference? Actually Phil Rushton had suggested something similar as the explanation, but Herlihy expanded on it in this book (though he probably never heard of Rushton).The Black Death killed off something like half of Europe's population within a decade in the mid-14th century. The short-term destructive effect was incalculable. But Herlihy argues that those who were left unkilled were suddenly provided with huge resources, both natural and human, and much technical innovation became possible, which in turn launched Europe onto the road to the Industrial Revolution. As an example - the most dramatic one - he called the Gutenberg printing press a direct result of the Black Death. (p. 50) Not only was this a major technical innovation, the printing press had a greater influence than, say, a more efficient way to grow food: printing helped disseminate knowledge, even though, at first, most of this knowledge concerned religion and then only later science and technology.Samuel Cohn used the Introduction to criticize Herlihy, which I think is not only odd but in poor taste, because Herlihy was already dead when Cohn wrote it. Cohn doubted the printing press (and by analogy, Herlihy's other examples) made much difference: far more book were printed many years after Gutenberg, he says, when population growth was surging again. I think Cohn misses the point: the INVENTION of the Gutenberg printing press was made possible by the Black Death, which made labor costs sky high by killing off many scribes. That many more books were printed with a fast-increasing population is not surprising: the demand for books increased with headcount. But Herlihy argues that without the Black Death, Gutenberg might not have had to invent his printing press. Herlihy's other examples include firearms.Cohn points out that gunpowder and cannons were already known before Black Death. True enough. But he cannot convincingly prove that the Black Death didn't create a need for the widespread use of firearms in war. Cohn raises many other questions. A tough one is: why didn't the Middle East experience a cultural resurgence after the Black Death, which struck Europe just as hard? Herlihy has no answer to this. Cohn also fails the mention the puzzling case of China. The 14th century was hard on China also - many millions died from epidemics almost identical with the Black Death. But China started falling behind Europe soon afterwards. Why did Europe and not China benefit from the Black Death? (My guess is China suffered less human loss than Europe did, and as a result could not free up more resources to break what Herlihy calls the Malthusian deadlock - the constant growth i

Excellent expository essay in three parts

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

This book is not a broad survey or a complete history. It is quite short and assumes a good bit of knowledge of the plague and of general European history.He addresses three issues. First, he points out that historians really can't be sure of the composition of the plague itself. Was it actually all just bubonic plague, or some combination of various other diseases? Second, what were the economic effects of the plague? Did the relative scarcitity of labor following the plague break Europe out of a 'Malthusian deadlock' into a growing economy? Finally, what was the effect of the plague on the social order? Did it help to Christianize Europe?The book is written in a fairly academic style, but it is very readable. My biggest complaint is that is so short. I wish he had written more.

Great read for those interested in the Black Death.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I picked this book as an assignment for my Western Civ. class in college. It turned out to be a very interesting look at the Plague and its effects on Medieval society. I especially enjoyed Dr. Herlihy's theories about the spread of Christianity as a result of the Plague. It was also very interesting to learn more about the medical aspects of the Plague, as well as its implications on European society and commerce. A great read for anyone interested in the Black Death!!