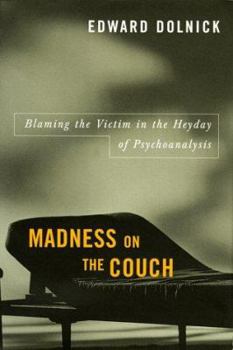

Madness on the Couch: Blaming the Victim in the Heyday of Psychoanalysis

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Details the failure of psychiatry to cure mental illness.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0684824973

ISBN13:9780684824970

Release Date:October 1998

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:368 Pages

Weight:1.44 lbs.

Dimensions:9.6" x 1.1" x 6.4"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

Stinging Indictment of psychoanalysis

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This book is an easy-to-read and thoroughly entertaining critique of psychoanalysis attempt to treat schizophrenia and autism through talk therapy. Though largely anedotal, Dolnick presents a strong case that psychoanalysis is speculation cloaked in scientific garb. Instead of utilizing a rigorous method of testing their hypotheses, psychoanalysts seek confirmation and try to fit observable phenomenon into their pre-existing schemata. The audacious arrogance of Freud and his followers made them immune to contrary evidence and resistant to other methods. Moreover, Dolnick suggests that psychoanalysis feeds into the self-aggrandizement of the psychoanalyst: they are the all-knowing interpreter of their patients; they are in the privileged position. With this sort of foundation, it is no wonder psychoanalysts were able to reck havoc on parents of schizophrenic and autistic children. Without any basis in fact but only through the deductions of their own schemata, psychoanalysts condemned parents for causing schizophrenia and autism. Some through willful fraud, others through self-delusionment distorted their own success rate. To admit mistakes, would render their enterprise vulnerable and knock them off the pedestal they place themselves upon. I don't understand some of the criticism of Dolnick's tone as "sarcastic" and "depressing". Maybe Dolnick does have a bit of an axe to grind but what better service to grind an axe with than in these incidents. These psychoanalysts caused more problems than they solved. They condemned parents for something they weren't responsible for and gave these same parents a false sense of hope that they could help their children.

Fascinating demolition of psychoanalysis

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The madness in the title more properly should be assigned to the chair behind the couch. That is Dolnick's point: the shrinks themselves were mad. In their madness they blamed the parents for the illness of their children, particularly the mother. How did the schizophrenic get that way? He had a "schizophrenogenic" mother, typically a loveless woman who rejected the child while dominating it psychologically. How about autism? The victim of a "refrigerator mother" who withheld love from the child. The obsessive-compulsive disorder? Ditto, although here the patient was also singled out since the patient knew what he was doing, but just would not change. Dolnick does a great job of chronicling the delusive mind set of the shrinks who fought tooth and nail against any sort of biological explanation of mental illness even though the evidence was clear. They clung like barnacles to their delusions that these diseases were psychological because, should they admit that they were physical illnesses, caused by something physically wrong in the brain, their fraudulent "talk therapy" would be seen as it really was, useless, and their entire professional lives would be exposed as a waste.Dolnick begins with a studied demolition of Freud and psychoanalytic psychology. He exposes Freud's delusions about the causation of mental disease, about the nature of dreams, his obsessive belief in "symptoms as symbols," and especially his arrogant lack of scientific method. Dolnick shows how the "great" man bamboozled the psychiatric profession with his almost magical way with words, turning yes's into no's and vice versa as the situation required. The Freudian canon that sex was at the heart of every neurosis was so broad and varied that almost any convenient explanation could be found within. Soldiers suffering from shell shock would seem to be an exception, but no. Dolnick quotes Freud as arguing that "Mechanical agitation...[the hellish roar and rumble of trench warfare] must be recognized as one of the sources of sexual excitation." (p. 37)Freud's ability to delude both himself and his colleagues is exemplified in the notorious case of Emma Eckstein who was operated on by Freud's friend, Wilhelm Fliess. She was suffering from "stomach ailments and menstrual pain" and "had problems walking." Fliess performed a nose operation but it did not go well. For one thing Fliess left some surgical gauze in Eckstein's nose. As she continued to hemorrhage Freud observed, "she became restless during the night because of an unconscious wish to entice me to go there; since I did not come during the night, she renewed the bleedings, as an unfailing means of rearousing my affection." (p. 47)The crux of Dolnick's book, though, is not about Freud but about his followers, especially the psychoanalytic psychiatrists from what he sees as the heyday of psychoanalysis, roughly the middle third of the twentieth century. He expresses the central delusion of the therapists

Extremely well written and researched; a learning experience

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 27 years ago

This book was more than I expected. Although it deals with a limited field of psychiatry, namely psychoses of schizophrenia, autism and OCD, as they relate to misuse of psychoanalysis in their treatment, the author gripped me from the start. I enjoyed the historical review of psychiatrists in the heyday of Freud, Jung, Adler, and was interested to learn of American counterparts in the mid 1900s. The description of case-histories was interesting, specifically the author's personal interviewing of these patients and patients families. In the ever evolving field of medicine, will we return to some of Freud's original theories? It will be interesting to follow. A new theory as to a possible treatment for autism using growth hormone, I believe, invites new debate. What does the author know and think about this newest treatment?

Brilliant, illuminating addition to history of medicine

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 27 years ago

"Madness on the Couch" is not only a riveting read -- I consumed half of it at a single sitting -- but an important contribution to the history of medicine. In chilling detail, Edward Dolnick documents those mid-20th century decades in which psychoanalysts used "talk therapy" to treat disorders like schizophrenia, autism, and obsessive-compulsive disorder and, in their unscientific quest for a cause, concluded that these conditions -- still largely unexplained but known to be the result of neural imbalances in the brain -- must have been the result of bad parenting. Most often, making a distressing family situation intolerable, they blamed the patient's mother.Hindsight is a tricky tool in writing medical history. It is easy to marvel now, for example, how blithely many leading 19th century surgeons rejected germ theory to the bitter end, resisting for decades mounting evidence that their own bacteria-laden fingers and instruments were killing patients. Dolnick, to his credit, is sympathetic to context as he traces the psychoanalysts' path of reasoning, showing that -- within the elaborate framework of Freudian belief -- their wrongheaded conclusions often seemed entirely logical. Those were the days soon after World War II when the study of genetics, discredited by Nazi experimentation, was seldom pursued. And those were the days when the only therapeutic alternative for schizophrenia was lobotomy. ("What is going through your mind now?" asked one surgeon as he sliced through the lobes of the brain. "A knife," the patient replied.)On the other hand, Dolnick argues, by the 1960s the testing of evidence for medical conditions by means of controlled experiments was well established. Yet many questions that should have raised red flags went disregarded by the psychoanalysts. If schizophrenia and autism are caused by bad mothers, for example, how come many mothers of schitzophrenics and autistics also have normal children? Brushing such questions aside, the pyschoanalysts relied on anecdotal stories. One eminent American psychiatrist constructed a whole career of influential teaching and writing ("We now know that the patient's family of origin is always severely disturbed") on an uncontrolled study of only 17 cases. Other pschoanalysts were scarcely more rigorous. "Ignorant of science and disdainful of it, they failed to follow up on leads they should have checked out," Dolnick says.The history of effective medicine -- the era in which consulting a physician offers more chances of being successfully treated than not -- is barely more than a century old. "Madness on the Couch" illuminates a medical saga, played out within our own times, of how the best intentions can have the most disastrous effects. It is a brilliant and compelling book.