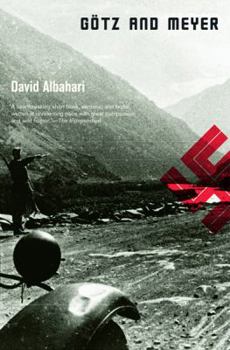

Gotz And Meyer

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A Jewish schoolteacher tells the story of Wilhelm G'tz and Erwin Meyer in the process of researching the deaths of his relatives during World War II. These two SS officers were assigned to drive a... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0151011419

ISBN13:9780151011414

Release Date:January 2005

Publisher:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Length:168 Pages

Weight:0.72 lbs.

Dimensions:8.0" x 0.8" x 5.5"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

"Once you become part of the mechanism,you assume the same responsibility as every other part."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This is an exceptional and different book about the Holocaust.It is written ,not by a survivor,but by someone born in Serbia a number of years later, in 1948. Having lost a large number of his family to Hitler's Final Solution,he does a large amount of research to find out what happened to them,what it was like at the time,and what went through the minds of the perpetrators as well as the victims. Gotz and Meyer,were two SS Non-Commisioned Officers, who the author had found to be charged with the responsibility of transporting about 5,000 women and children from Belgrade's Fairground concentration camp to Jajinci for extermination.They drove the truck,which held about 50 prisoners. The victims were led to believe they were being taken to a better place and would receive decent treatment. A short time after the truck left,it stopped,and the drivers would connect a hose from the exhaust to an attachment that would direct the exhaust fumes into the enclosed truck,thus killing all the prisoners as it continued on its way. Upon arrival,other prisoners removed the corpses and dumped them into trenches already dug by other prisoners. Gotz and Meyer really met face to face to the victims. They seemed to think they were just truck drivers;despite the fact that they really were the murderers when they connected up the exhaust pipes. The author tries to get into the minds of the SS and the victims, trying to determine how they rationalized their actions.Try as he might,there are no way this evilness can be understood and he finds it is madness all around;and he almost loses his mind in attempting to make sense out of it all. I guess the only thing that comes out of all the author's effort is that there is no understanding madness.

The seeds of remembering

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Describing the Holocaust, Hannah Arendt wrote of "the banality of evil." In this attempt to understand the unspeakable, Albahari's unnamed narrator, a Jewish schoolteacher in Belgrade, begins not in anger but with empathy. Götz and Meyer are two noncommissioned SS officers, whose names he has turned up in the records, while researching the fate of his own forebears. He sees them as ordinary Germans, family men perhaps, fond of children, and taking pride in the efficient accomplishment of their job. That this job is to drive the sealed truck that asphyxiates 100 Jews with engine exhaust on each trip from the holding camp to the burial fields does not lessen his interest in inviting them into his mind, and talking with them in his imagination. Eventually, just as his obsession with the ordinary begins to verge on madness, he embarks on a symbolic reenactment with his own pupils, thus "sowing the seeds of remembering" for future generations. This short book, which flows in a single unbroken paragraph of lucid prose, is impossible to put down, and the almost genial understatement of its opening in no way diminishes its cumulative power.

"I am a protagonist from books that have not been written."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

The speaker of this long monologue by Serbian author David Albahari is a teacher of Serbo-Croatian language and literature, a 50-year-old Jewish man who has been trying to fill in the spaces in his family tree after World War II in Yugoslavia. The extermination of Jews started early in Yugoslavia, with most of the Jewish men of Serbia shot to death by the fall of 1941, and "the Jewish Question in Serbia almost completely solved" by April, 1942, when virtually all Jewish men, women, and children were dead. Imagining the lives of Gotz and Meyer, two SS guards who were responsible for over 5000 Jewish deaths, the speaker examines the events for which Gotz and Meyer were responsible between November, 1941, and April, 1942--the executions of one thousand Jews per month in the Belgrade Saurer truck they drove daily. The truck, with its hermetically sealed rear compartment, had a hole in the floor into which the exhaust was pumped as prisoners were being taken from the Belgrade Fairgrounds camp, where they were housed, to "better" accommodations elsewhere, "a concern of the German government for the good of the prisoners" that the speaker finds "touching." Albahari exhibits a mordant humor as his speaker imagines the inner lives of Gotz and Meyer. Often juxtaposing horrifying atrocity against simple, folksy observation, the speaker fantasizes about "Gotz, or was it Meyer," a phrase which echoes throughout the narrative. As he puts himself into their minds, he wonders if they had nicknames, if their wives had pet names for them, and if they ever regretted what they were doing, since they were so good at their jobs. "Killing, too, is an art," the speaker says, "and it has its own rules." As Albahari includes the terrible statistics, he also exhibits the dark ironies of the circumstances, setting the facts into sharp relief and increasing the shock. He imagines reports on the load distribution of the bodies in the truck and how they might have contributed to a broken rear axle, contemplates the comforting effects of a lightbulb in the truck as the bodies start to fall, and "worries" about the red tape of co-ordination. Gradually, Gotz and Meyer become more human for the reader, and when the speaker takes his class on a field trip to the site of the Fairgrounds camp, he asks each to imagine himself/herself as one of his relatives. As the horror of the events gradually register with the students, the teacher comments: "Memory is the only way to conquer death," he says, "even when the body merely goes the way of all matter and spins in an endless circle of transformations." A strange novel of the Holocaust, all the more shocking because of the contrasts between the facts and the dark humor, Gotz and Meyer is a memorable short novel and worthy addition to Holocaust literature. n Mary Whipple

( 4.5) "Death is not a balloon but an anchor."

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Gotz and Meyer. To the narrator who has lost all his family to the Holocaust, these non-commissioned SS officers are nondescript, almost featureless, blonde-haired, blue-eyed. Without doubt, they are loyal to the Reich and the Fuhrer. Their truck, a Sauer, is specially made, hermetically sealed and can hold up to a hundred people at a time. The occupants think they are leaving a terrible camp, the Fairgrounds, near Belgrade, in Serbia, climbing cooperatively into the vehicle. After a trip that ends with the death of the passengers, their corpses are unloaded by seven Serbians, who drag them unceremoniously to a ready mass grave. Most of the occupants are women and children, the Serbian Jewish men long since murdered, save a few to keep order in the camps. The Nazi's have a systematic design for deceiving Jews, setting up the Jewish Administration, convincing them the camps are really reception centers before transportation to an undesignated country. None of the incarcerated Jews ever try to run away, so thoroughly entrenched in the deception, participants in a cogent and orderly world to the end. Gassing is cost-effective, considering the price of ammunition, not to mention easier psychologically on all concerned, but it is the very efficiency that begins to eat at the narrator, as he sifts through facts about Gotz and Meyer's particular assignment, the amount of food and milk allotted to each prisoner, the harvesting of false hope to assure compliance, the stoic resolve of the commanders, the willing Jewish Administration trying to alleviate the suffering in the camp. His imagination at times paralyzed by conjured images, the bland, dutiful Gotz and Meyer become the stuff of nightmare, the narrator's family members climbing obediently into the truck, their innocence irrelevant. In his mind, the narrator holds conversations with Gotz and Meyer, positing questions about their smoothly consummated work, until finally, the Fairgrounds is silent, empty of life. The author's construct is all the more powerful when told from the perspective of the two faceless men, their surgical precision a contrast to the humanity they deliver to death day after day. The banality of evil achieves a curious balance, the horrors more chilling for their impersonal exactitude. But all of these voices, these imagined personalities have vanished into the past, buried by Serbians in mass graves, their youthful hopes extinguished by the carbon monoxide of a death vehicle, the harbinger of their redemption, "In the tangible world you have no choice". In a most ingenious manner, the narrator rejoins his lost relatives, finding a measure of peace after a harrowing but necessary journey. At a time when historical revisionists seek to deny the existence of the Holocaust, such books are a reminder that "memory is the only way to conquer death". Luan Gaines/ 2005.