Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 315

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

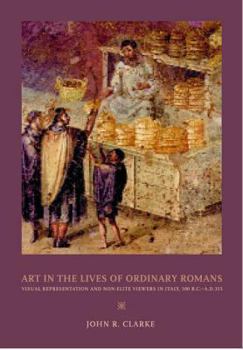

This splendidly illustrated book brings to life the ancient Romans whom modern scholarship has largely ignored: slaves, ex-slaves, foreigners, and the freeborn working poor. Though they had no access to the upper echelons of society, ordinary Romans enlivened their world with all manner of artworks. Discussing a wide range of art in the late republic and early empire--from familiar monuments to the obscure Caupona of Salvius and little-studied tomb reliefs--John R. Clarke provides a tantalizing glimpse into the lives of ordinary Roman people. Writing for a wide audience, he illuminates the dynamics of a discerning and sophisticated population, overturning much accepted wisdom about them, and opening our eyes to their astounding cultural diversity. Clarke begins by asking: How did emperors use monumental displays to communicate their policies to ordinary people? His innovative readings demonstrate how the Ara Pacis, the columns of Trajan and of Marcus Aurelius, and the Arch of Constantine announced each dynasty's program for handling the lower classes. Clarke then considers art commissioned by the non-elites themselves--the paintings, mosaics, and reliefs that decorated their homes, shops, taverns, and tombstones. In a series of paintings from taverns and houses, for instance, he uncovers wickedly funny combinations of text and image used by ordinary Romans to poke fun at elite pretensions in art, philosophy, and poetry. In addition to providing perceptive readings of many works of Roman art, this original and entertaining book demonstrates why historians must recognize, rather than erase, complexity and contradiction and asks new questions about class, culture, and social regulation that are highly relevant in today's global culture.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0520248155

ISBN13:9780520248151

Release Date:April 2006

Publisher:University of California Press

Length:418 Pages

Weight:2.35 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 7.1" x 10.0"

Customer Reviews

1 rating

How Important Art Was to Roman Non-Elites

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

"The glory that was Rome" has become proverbial. But John R. Clarke, a professor of the history of art, argues that the monuments of that glory, like the Arch of Constantine and the portraits of emperors, are not the full story. There was other Roman art, like wall paintings and mosaics, which, especially if they were decorations in ordinary houses in Pompeii, were not previously regarded as art within art history. When Clarke first began studying Roman art, these were objects of study in the everyday life of Romans. This has changed, and "everyday" art of the Romans has become a respected target for academic study, not only for itself but for what it can tell us about the majority of Romans. In _Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C. - A.D. 315_ (University of California Press), Clarke lays out the importance of art made or commissioned by such lowly ones as slaves, former slaves, and freeborn workers. Emperors and the wealthy represented themselves in artwork carrying out official and prestigious practices that would demonstrate their importance. Non-elites tended more to want to depict ordinary acts, working, drinking, even brawling. It isn't surprising that the "unofficial" art could tell us more about daily Roman life.Clarke does begin by discussing how non-elites viewed the official art of the emperors, and then proceeds to the art that non-elites produced. There are many examples here of art in domestic shrines, business-advertising, status boasting, and humor-provoking. Clarke speculates, for example, that a painting from Pompeii previously thought to depict a man selling bread is actually a man giving out a bread dole. There is no evidence of commerce; the receivers of the bread are exultant and do not themselves give up money. The painting comes from a small house, not that of an elite citizen. Clarke says that most likely this is the house of a baker who was prosperous, decided that at some point he would give bread away, and wanted to be depicted in his act of charity. Viewers of his painting would have been reminded of the event, and the baker's prestige would have risen. A completely different commemoration of a particular event is the painting from another house of a riot in the Pompeian amphitheater. This depicted a real event arising somehow from hooliganism during games between the home and visiting teams, an event that caused Rome to forbid all gladiatorial shows in Pompeii for ten years. The owner of the house went to the trouble of having an event that might be thought of as shameful commemorated on his walls. Clarke gives evidence, from the placement of the picture and the subject, that the owner was a gladiatorial fan, who honored the gladiators by putting on display a commemoration of a riot held in their honor, perhaps a riot in which he himself took a glorious part. Unlike the citizen who wanted people to remember the honorable act of giving