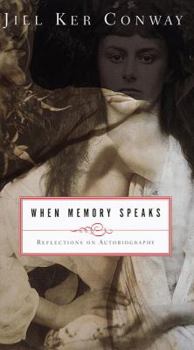

When Memory Speaks

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

J ill Ker Conway, one of our most admired autobiographers--author of The Road from Coorain and True North--looks astutely and with feeling into the modern memoir: the forms and styles it assumes, and... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0679445935

ISBN13:9780679445937

Release Date:March 1998

Publisher:Alfred A. Knopf

Length:205 Pages

Weight:1.05 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 5.8" x 9.6"

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

a gem of a book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

A deep, thoughtful and wonderfully written look at women's autobiography. It stirs the cauldron of memory and makes you want to open up locked away plans for writing. The author communicates presence of Being in her work, and a touch of Grace all throughout. I have read many, many books on autobiography, but this one ranks as my favorite. You won't be disappointed, and you might be encouraged to write your own story.

Valuable For Its Deep and Thoughtful Discussion

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Jill Ker Conway, author of The Road from Coorain and True North, is one of our most widely-read and admired memoirists. Her books are praised for their graceful explorations of our most urgent questions of personal meaning: Where do I come from? What is my story? How has my past experience shaped me? In When Memory Speaks, Conway turns her attention from her own life to the stories of other lives, looking at the modern memoir and the way it reflects our culture and ourselves. She isn't writing exclusively about women, but this is a help, for she uses the narrative patterns of men's stories about their lives to show how women's memoirs evolved, comparing and contrasting the forms. Using examples from the autobiographies of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Benjamin Franklin, David Livingston, Conway shows that men's stories typically involve the self-made hero who creates his life in conflict with social or natural forces. In men's memoirs, she says, the male hero reveals himself as acting upon the world in order to give it the shape and meaning he chooses. Conway argues that until very recently, women's memoirs have shown quite a different pattern. They reveal the autobiographer as a "romantic heroine" who is acted upon, who seems to believe that she lacks control over her destiny and tends to censure her shaping role in her own story in order to satisfy her readers' expectations. Conway shows, for instance, that Jane Addams developed the the Hull House project after several active and energetic years of careful study of European social reform--and yet she writes about her idea in the passive voice, as if she were its agent, rather than its creator. In this way, Conway says, "Addams is able to conceal her own role in making the events of her life happen and to conform herself to the romantic image of the female...shaped by circumstances beyond her control" (p. 49). And, Conway points out, even such assertive feminists as Germain Greer (in Daddy, We Hardly Knew You) and Gloria Steinem (Revolution From Within) reveal in their memoirs the difficulty of redefining ourselves as heroes of our own stories. Conway's book is valuable for its deep and thoughtful discussion of the history of women's stories, compared to and contrasted with the autobiographical stories of men. But it is also valuable for what it has to say about the memoir itself, as a way to help us understand ourselves and our past experiences. If we recall the past as a chaos of random bits of good and bad luck that shaped us willy-nilly, we are likely to be victims of a similar future. If we see the past as the product of our choices and actions, we are better able to shape our futures: "We travel through life guided by an inner life plot--part the creation of family, part the internalization of broader social norms, part the function of our imaginations and our own capacity for insight into ourselves, part from our groping to understand the universe in which the planet we inhabit is a spec

Autobiography, Feminism, and the Self of Modern Fiction

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

This book is a fascinating, clear, balanced, and informed look at what Conway calls "the most popular form of fiction for modern readers"--autobiography. Although Conway is drawn to modern themes of race and gender, she also has a keen critical eye, balances the popular with the less-well-known, and the present with the past. She focuses on meaning making, the way people see their own lives, and the lessons they draw for others from them. For better or worse (and often worse) she argues, the Homeric Greek hero on his action packed odyssey is archetype for meaningful autobiography. Church father Augustine in his Confessions (c. 400) internalized the action, chronicling his attempts to resist temptation and submit to the will of God.Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his Confessions (1871) attempts to succeed on the temporal level, to be a worldly success in touch with self and emotions beyond society's external laws. Benjamin Franklin in his Autobiography (1818) defines such worldly success in economic terms based on diligence and delayed gratification. The analysis of 19th century women's rights leaders such as Harriet Martineau and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are artfully analyzed through their autobiographies, as are colorful female personalities less obviously political such as stepbrother-abused Virginia Wolf (1882-1941) and the hilarious Mabel Dodge Luhan (1879-1962)who was married four times (and had an affair with D.H. Lawrence) and wrote a four-volume memoirs entitled Intimate Memories. More familiar feminists such as Australian Germain Greer, Gloria Steinem ("full-time feminist leader, slipping into the role of caregiver for the feminist movement and unable to care for herself") are also analyzed with a critical focus of Conway's refreshingly non-monolithic feminism. Because of her rare combination of empathy and critical clarity, Conway excels when she is examining more marginal characters such as lesbian May Sarton's 1968 Plant Dreaming Deep, the 1974 Flying by lesbian Kate Millet (who appeared on the cover of Time),black lesbian Audre Lorde's 1982 Zami, A New Spelling of My Name, and so on. Conway also analyzes gay male autobiographies such as historian Martin Duberman's 1991 Cures, and A Different Person (1993) by James Merril (son of Charles E. Merril, one of the founders of Merril Lynch). She examines James/Jan Morris's transexual account in Conundrum, and decides that such stories are intrinsically more essentialist (structurally sexist)than simple gay and lesbian autobiographies. I am not sure I agree with all of Conway here--her definition of postmodernism seems too simple, and it is not clear that the true goal of autobiography writing is to own up to ourselves as significant actors in the drama of our own existence, rather than victimlike or overly modest ("feminine") being to whom things happen. To know that we would have to know the status of free will, which we don't, and there is the added danger (also an artistic one, although it can