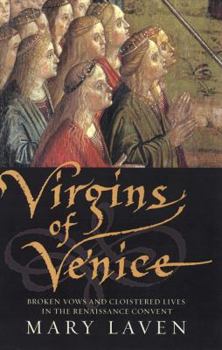

Virgins of Venice: Broken Vows and Cloistered Lives in the Renaissance Convent

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Venice in the late Renaissance was a city of fabulous wealth, reckless creativity, and growing social unrest as its maritime empire crumbled. It was also a city of walls and secrets, ghettos, and... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0670031836

ISBN13:9780670031832

Release Date:March 2003

Publisher:Viking Books

Length:282 Pages

Weight:0.05 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.5" x 8.7"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

get thee to a nunnay!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 13 years ago

i really enjoyed this book. i was expecting it to cover more of the italian renaissance (mid to late 1400's), but rather it covered in bulk the late 1500s to mid-1600s. still a really good read. hopefully she will publish some more writings, as i found myself rather sad i was done.

I expected more of this book....

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

...even while I was reading it. Author Mary Laven did most things right, in terms of historiography, with excellent research into primary sources - chiefly trial records, but also including the writings of clerical reformers and of a few nuns themselves - and proper attention to NOT overstating the conclusiveness of her research. What she offers is very substantial, as previous reviewers have noted, but also oddly partial. And I mean "partial" in both senses. First, it seems that Mary Laven is partial, i.e. partisan, to rather specific views of feminism and feminist history. I won't argue for or against those views, lest I bias any prospective readers. Second, Laven's portrayal of convent life in 16th Century Italy is partial, in that it gives only a small part of the whole picture. Unless the reader has previous knowledge of the daily routine of chanting nuns, she/he will finish reading Laven's book with the impression that life in the convent was monstrously idle, a natural environment for discontent and mischief. Only the most minor mention is made of the chanting of the liturgical Hours, which was the nuns' chief form of worship and service to the community by its accumulation of grace. No mention at all is made of other music in the convents, yet musical studies and musical performance were undertaken very seriously by quite a large percentage of the noble chanting nuns. Recent musicological work has produced evidence that women in the convents of Milan and Venice wrote substantial music for their own use, and some of that music is as fine as any written by men in the less-restricted outside world. Take your ears to hear the CDs of Lucrezia Vizzana and Chiara Margarita Cozzolani, both life-long convent nuns, as performed by Musica Secreta. Unfortunately, without some recognition of the substantial lives of cloistered nuns during the late Renaissance, Mary Laven's book gives us the impression of mostly wasted lives of women who were sacrificed as individuals by their patriarchal society. There's truth in that, but only partial truth. And I have to say, I never ever foresaw that I'd be defending the walls of any convent!

An Important Study of Convent Life

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Laven's scholarly study (originally her doctoral's thesis) is nonetheless a readable account of nunnery life in early Renaissance Venice. She describes a fascinating slice of 16th century life. What is remarkable is that the 'slice' is actually quite large. As Laven relates, noble women (most professed nuns were noble) had few options. Most families concentrated their financial resources in a dowry for only one daughter and the rest commonly went to the convent. For many of these women life in a nunnery was not voluntary. As part of the Church's defensive reaction in the Counter-Reformation, Venetian convents became much more strictly enclosed by the strictures of the Council of Trent. The enclosure laws greatly benefited Laven's work because most of her material comes directly from court records. These sources are both book's greatest strength and its weakness. The records provide insight into the behavior of real people, individuals with names and families, in and around nunneries. Given the lack of other available resources, the reliance on court records distorts our view because we mostly only read about those situations that made it to court. Fortunately for us, convent life was quite strictly regulated, yet nuns were also determined to have dealings with the outside world - many of them non-sexual - so Laven has access to many records. A very interesting case study. The Church was so central to medieval and Renaissance life that anyone who wants to understand those periods must understand the role of religion and the Church as an institution. Laven's book is highly instructive and highly recommended.

Difficult to stop reading

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

If we could travel back in time, and our machine landed in 16th century Venice, what would you like to see? Grand palaces, and the people who lived in them? Carnival time in the Piazza of San Marco? Perhaps life on the streets? What about life in a convent? Too dull, you think? Then, you have not read Mary Laven's Virgins of Venice, a remarkable journey into the lives of the women who lived in the fifty or so convents that existed in Venice at the time. Nunneries were not only spiritual houses, but also end stations for noble women who could not be given away in marriage by their families. By using reports of investigations and trials, together with statements that came from the nuns themselves, Laven opens a world of suffocating oppression and enforced chastity, but also a world of determination from the nuns to lead a life as normal as possible. Contact with the outside world might have not been allowed, but the courts were full of incidents where both outsiders and nuns had breached the law. For instance, we learn that Zuana, a "gossip", kept hens for Madonna Suor Gabriela, and that in exchange, Suor Gabriela provided Zuana with wine and other commodities. This and many other stories make this book impossible to put down, since we feel anger, sadness, despair and sympathy for those women whose lives were condemned from the moment they entered the convent. On the other hand, we can't help but to feel glad that the nuns did everything they could to fight back. From being petty to actually engaging in sexual acts, these nuns will forever be a remainder that no matter time and place, human beings will do the impossible to lead dignified lives. Bravo, Leven!

Behind Convent Walls

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

In the wall of the Arsenal in Venice is an arch of the demolished convent Santa Maria delle Vergini. The convent had been one of the grandest of thirty-odd Venetian convents. There is a plaque below the arch that reads, "Hope and love keep us in this pleasant prison." Convents were like prisons, in many ways, and many of the inhabitants were reluctant prisoners, rather than volunteers for God. In an amazing account of convent existence and day-to-day life within, _Virgins of Venice: Broken Vows and Cloistered Lives in the Renaissance Convent_ (Viking), Mary Laven has expanded upon insights hinted at in Dava Sobel's _Galileo's Daughter_, wherein the daughter showed herself interested in science and in sending her father shirts and cookery. Some of the nuns may have been devoted to God, but even they had to be busy with laundry, cooking, and herbal remedies to keep the convent going. They were also not immune from gossip, laughing, friendship, and sexual intrigue. The convents in the 16th and 17th centuries were supposed to be islands of sinlessness walled away from the outside world, but Laven shows that sinless or not, the nuns had to participate in a larger society, and inescapably took on that society's characteristics.Convents were supposed to keep nuns from the outside world and vice versa. There were veiled and grated communion windows where the nuns could line up and receive the host from the priest, without actually entering the church. There were walls to keep nuns from public view, and to keep them from looking out upon the sinful world. For passing things in and out of the convent, there might be a _ruota_ or wheel, a sort of revolving door that would prevent glimpses in and glimpses out. Convents were vital to the Venetian nobility. If a daughter could not be married, or could not be put on the marriage market with the enormous dowries Venetian law required, the convent was the one place she could go. Most of the nuns had the "forced vocation" of the convent imposed upon them, and others were tricked into it by relatives, some within the convent, who had misrepresented the benefits of such a life. There was stratification within the convents that mirrored society without. The aristocratic nuns could dress as they were used to, and they kept their family names, indicating a secular identity. Of course there were sexual violations; Boccaccio's tales of convent hanky-panky might have been satire, but he knew that sexuality would show itself. _Virgins of Venice_, despite its lurid subtitle, is certainly not about sensational sex stories. This is a work of serious scholarship, but it is humorous and compassionate. Laven has drawn from contemporary sources, including the reports of inspections of the state magistracy that had been set up "to enforce the new laws that aspired to obliterate all contact - from the most innocent and inconspicuous to the flagrantly sexual - between the city's nuns and the outside world." Laven