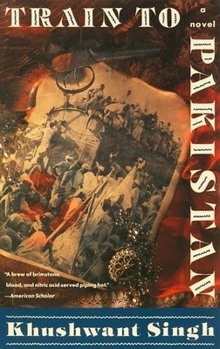

Train to Pakistan

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 'Train to Pakistan', truth meets fiction as Khushwant Singh recounts the trauma and tragedy of partition through the stories of his characters - the stories that he, his family and friends... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0802132219

ISBN13:9780802132215

Release Date:February 1994

Publisher:Grove Press

Length:192 Pages

Weight:0.45 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.3" x 8.2"

Related Subjects

Asia Classics Contemporary Fiction Genre Fiction Historical History India Literary Literature & FictionCustomer Reviews

4 ratings

Train to Pakistan: Breaking the Cycle of Revenge

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Ethnic conflict has been a staple of cross-cultural contact for as long as more than one race and religion have tried to co-exist. In the border between Pakistan and India, the theme of revenge killing calling for ever more revenge killing has found a clear voice in TRAIN TO PAKISTAN by Khushwant Singh. Nearly everyone in the novel is flawed to some degree with the effects and aftereffects of ethnic cleansing. There is no clear cut hero although a criminal named Jugga comes closest. Jugga is a Sikh thief who happens to take a Moslem woman as a lover. Their illicit relation is a microcosm of all that is terribly wrong when the cut of a person's beard counts more than the content of his soul. Jugga is far from an angel, but he slowly grows in stature from the baseness of his profession to one who is forced to contemplate the consequences of his own role in the ongoing cycle of killing between Sikh and Moslem. He is used as a pawn in the Sikh's killing of innocent Moslems, and his choice is the same that all men of revived conscience have had to face in similar such times: should he participate willingly even eagerly in the proposed slaughter of a train of deported Moslems shipped unceremoniously to Pakistan or should he speak out against the insanity that is insane only to him? The various flaws of all the characters of the novel--their vicious caste system, their willingness to demonize other races, their unwillingness to question even the most fundamental elements of their dogma--all stem from the cycle of killing that did not begin with the trainload of Sikh corpses that entered the sleepy town of Mano Majra in India. This mass killing is simply a sociological given: its root cause goes back uncounted centuries of strife between Moslem and Sikh yet it is hailed by Sikhs as 'the' reason to replicate the slaughter of Moslems on yet another train headed to Pakistan. Khushwant Singh portrays a society of confused, angry villagers who see no way out of the ongoing cycle of killing except to perpetuate that killing. Singh suggests that the men of good conscience who try to make even token attempts to bring this insanity to a halt are few and far between. The events of clashes between Sikh and Moslem that have occurred since this book was first published in 1956 further suggest that such men of good conscience have grown fewer in number.

A harrowing journey to the inevitable...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

The summer of the Partition of India in 1947 marked a season of bloodshed that stunned and horrified those living through the nightmare. Entire families were forced to abandon their land for resettlement to Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India. Once that fateful line was drawn in the sand, the threat of destruction became a reality of stunning proportions. Travelers clogged the roads on carts, on foot, but mostly on trains, where they perched precariously on the roofs, clung to the sides, wherever grasping fingers could find purchase. Muslim turned against Hindu, Hindu against Muslim, in their frantic effort to escape the encroaching massacre. But the violence followed the refugees. The farther from the cities they ran, the more the indiscriminate killing infected the countryside, only to collide again and again in a futile attempt to reach safety. Almost ten million people were assigned for relocation and by the end of this bloody chapter, nearly a million were slain. A particular brutality overtook the frenzied mobs, driven frantic by rage and fear. Women were raped before the anguished eyes of their husbands, entire families robbed, dismembered, murdered and thrown aside like garbage until the streets were cluttered with human carnage.The trains kept running. For many remote villages the supply trains were part of the clockwork of daily life, until even those over-burdened trains, off-schedule, pulled into the stations, silent, no lights or signs of humanity, their fateful cargo quiet as the grave. At first the villagers of tiny Mano Majra were unconcerned, complacent in their cooperative lifestyle, Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and quasi-Christian. Lulled by distance and a false sense of security, the villagers depended upon one another to sustain their meager quality of life, a balanced system that served everyone's needs. There had been rumors of the arrival of the silent "ghost trains" that moved quietly along the tracks, grinding slowly to a halt at the end of the line, filled with slaughtered refugees.When the first ghost train came to Mano Majra the villagers were stunned. Abandoning chores, they gathered on rooftops to watch in silent fascination. With the second train, they were ordered to participate in burying the dead before the approaching monsoons made burial impossible. But reality struck fear into their simple hearts when all the Muslims of Mano Majra were ordered to evacuate immediately, stripped of property other than what they could carry. The remaining Hindus and Sikhs were ordered to prepare for an attack on the next train to Pakistan, with few weapons other than clubs and spears. The soldiers controlled the arms supply and would begin the attack with a volley of shots. When the people realized that this particular train would be carrying their own former friends and neighbors, they too were caught, helpless in the iron fist of history, save one disreputable (Hindu) dacoit whose intended (Muslim) wife sat among her fellow refugees. The

Stunning.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

When the monsoon rains wash a whole village of massacred babies, men, and women down the swollen river and past a small, peaceful community on India's border with the newly created Pakistani state, the residents of the village are aghast. When whole trains of newly slaughtered Sikhs and Hindus, not a passenger still alive, start arriving in their village from Muslim Pakistan, they hastily cremate and bury the remains, then retire to the temple in shock. When their own Muslim friends from the village are forcibly evacuated to Pakistan on ten minutes notice, the villagers know that the fabric of their lives is changed forever. With the immediacy of an on-the-spot observer to these events of 1947 and the passion of a sensitive writer impelled to tell a story, Singh mourns the seemingly permanent loss of compassion and tolerance which accompanied the separation of the Indian subcontinent into Hindu/Sikh India and Muslim Pakistan. His novel, written less than ten years after some of the events which are chronicled here, is filled with vibrant and realistic characters sometimes forced to make impossible decisions, characters who reflect the horrors of religious intolerance, which flourished when artificial boundaries were set up to divide India by religions. The book cries out against the losses of civility, tolerance, and life itself. With his love story of a Sikh dacoit and a Muslim weaver's daughter, told within an elegaic portrait of peaceful village life suddenly altered by religious strife, Singh draws the reader into the world of Mano Majra and its contrasts. He peppers the narrative with manipulative and grasping government officials and police, and outside agitators preying on residents' insecurities. The small world he creates so vividly becomes a microcosm through which the reader gains knowledge of the wider issues. Most remarkably, Singh holds himself above the ethnic and religious fray, reflecting his equal abhorrence of the Muslim atrocities and the Sikh response, "For each Hindu or Sikh they kill, kill two Mussulmans." Singh, writing this book in 1956, dramatically foreshadows the violence which has continued in this area to the present day. He makes us feel the sadness and the permanent loss to all the participants on all sides of this tragic conflict. Mary Whipple

If India interests you, you cannot do without this book.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

The first work by an Indian author that I ever read, Train to Pakistan is a superb book on many levels. It is a documentary of Punjab, its people, its culture. Its a narrative of the gruesome events that burned northern India in 1947. It is a story of the cultural, political, and intellectual atmosphere of India at the time. And it succeeds BRILLIANTLY. It brings the reader into the picture so vividly, its rather disturbing. If the reader is a product of the society the athor writes about, or is intimately familiar with it, and possesses any amount of intellectual spark, this book is an absolute must read. How much it'll mean to you if you are not familiar with the culture of Punjab, I don't know.