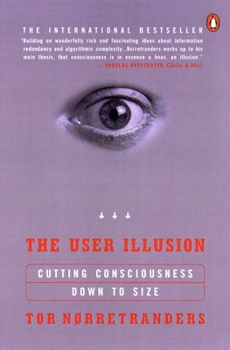

The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness Down to Size

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Explore the depths of consciousness through the essential groundbreaking international bestseller. "Finally, a book that really does explain consciousness."--John Casti, scientist and author of What Scientists Can Know About the Future With foundations in psychology, evolutionary biology, and information theory, Demark's leading science writer argues a revolutionary point: that consciousness represents only an infinitesimal fraction of our ability to process information. Although we are unaware of it, our brains sift through and discard billions of pieces of data in order to allow us to understand the world around us. In this thought-provoking work, Norretranders argues that our perceptions are not direct representations of the world we experience, but instead, illusions our brains craft to process it. More timely and relevant than ever, in light of rapid development in artificial intelligence and large language models, this informative study of consciousness provides the framework to reflect on the inner workings of the mind and understand the self. As engaging as it is insightful, this important book encourages us to rely more on what our instincts and our senses tell us so that we can better appreciate the richness of human life.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0140230122

ISBN13:9780140230123

Release Date:August 1999

Publisher:Penguin Books

Length:480 Pages

Weight:0.81 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.1" x 7.9"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A masterpiece of its kind

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I have been an expert and wide-ranging hypnotist for 25 years, and I strongly recommend this book to anyone interested in consciousness and in the sheer colossal *capacity* of the human mind. Norretranders shows just how impossibly much information we take in each moment, and how much is stored away, way more than we would ever suspect. I've witnessed this many times in my hypnotic work, the shocking capacity and depth and quality of memory that comes up in people in deep trance, even when the information is seemingly trivial. You have to experience it to believe it.

Human consciousness as a metaphor of the computer age

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This is a wonderful book translated from the Danish by Jonathan Sydenham, written more or less from a quantum physicist's point of view by a science journalist, but very readable, marred slightly by a Western bias. One of the things learned here is that it takes half a second for our consciousness to be aware of what we're doing. We don't notice this time lag because the mind back-peddles and makes it appear that we are on sync. The mind must backtrack so that our system will know when in real time an event took place. Reactions to things like removing a hand from a hot stove occur faster than our consciousness has time to be aware. So the mind just reconstructs the event and there is the illusion that we were aware in real time. We weren't. On page 256 is the example of a bicycle accident which happens too fast for the "I" to make a decision. The decision is made for the "I." So, is the "I" of consciousness really in charge or is that an illusion? The book's title gives Norretranders's opinion. I tend to agree. This is similar to the Buddhist idea that the ego-I of consciousness is an illusion. Norretranders makes a distinction between the "I" that is conscious and has a short bandwidth of perhaps 16 bits and the "Me" that is nonconscious and has a bandwidth of millions of bits. The "I" thinks it is in charge, but all it has is a slow-moving veto. On pages 268-269 Norretranders talks about how to get Self 2 (corresponds to the Me) "to unfold its talents." One method is to overload the "I" so that the "Me" is allowed to come to the fore. Give it "so many things to attend to that it no longer has time to worry" or "veto." Then the inner Me comes forward and plays beautiful music, etc. Similarly, we could say that the use of mantra, e.g., is effective as a meditation tool since it keeps the very verbal "I" occupied and allows the inner "Me" to come forward. Norretranders believes along with Julian Jaynes that consciousness arrived during recorded history or at least sometime during the first millennium B.C. He also believes that the use of mirrors helped to develop that consciousness. He notes (page 320) that "The use of mirrors became widespread during the Renaissance" which he says is "characterized by the reappearance of consciousness." (Thus we have our Western bias.) On the subject of the half-second delay in our conscious recognition of what is happening to us (discovered by Benjamin Libet): "If there were not half a second in which to synchronize the inputs, [from our senses] we might, as Libet puts it, experience a jitter in our perception of reality." (p 289) In reference to the title metaphor, we find on page 291: "The user illusion, then, is the picture the user has of the machine" [ i.e., his body and brain] "...[I]t does not really matter whether this picture is accurate or complete, just as long as it is coherent and appropriate. It is better to have an incomplete, metaphorical picture of how the computer wo

Mind opening

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The User Illusion is easily one of the best books I have come across in quite some time. It leaves you seeing the world very differently, realizing you don't have control over nearly as much as you think you do.The first hundred (or so) pages of the book don't mention conciousness at all. Instead they take you through a tour of how different fields deal with the notions of information, complexity and order. These are all woven together as the discussion of how our conciousness works begins.As the book progresses the author spends some time on philosophical issues, which seems to come out of left field but are actually very interesting. For example, he spends some time look at how the current views of conciousness apply to religion.Other reviews have mentioned that the material in this book is nothing new. Perhaps this is true. If you have done other reading in this area this book may be of less interest. However, if you're new to this area (as I was), this book provides a very thorough foundation of current thought.

One of the best explanations of conscious awareness so far

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I'm a big fan of the recent books attempting to explain consciousness: Dennett, the Churchlands, Owen Flannagan, Damasio, Edleman, Crick, Calvin, and so on. "The User Illusion" is unique among this crowd in two ways. First, it builds from a broader base of support, in information theory and thermodynamics. Second, it does not focus on the brain, but on the experience of consciousness. This seems at first to be a weakness, but it turns out to be a strength because what the author attempts to explain is how the experience of consciousness relates to the reality around us. In this book, a number of different lines of evidence converge on the profoundly scientific but uncomfortably counter-intuitive conclusion that conscious awareness is an extremely narrow bandwidth simulation used to help create a useful illusion of an "I" who sees all , knows all, and can explain all. Yet the mental processes actually driving our behavior are (and need to be) far more vast and process a rich tapestry of information around us that conscious awareness cannot comprehend without highly structuring it first. So the old notion of an "unconscious mind" is not wrong because we have no "unconscious," but because our entire mind is unconscious, with a tiny but critical feature of being able to observe and explain itself, as if an outside observer. This fits so well with the social psychological self-perception research, and recent research into the perception of pain and other sensations, that it has a striking ring of truth about it. This does lead to some difficult conceptual problems. A chapter is devoted to the odd result discovered by Benjamin Libet (also featured prominently in Dennett's Consciousness Explained, but not explained nearly so clearly there). Libet observed that the brain seems to prepare for a planned action a half second before we realize we have chosen to perform the action. This dramatically makes the author's point that human experience proceeds from sensing to interpreting teh sensation within a simulation of reality, to experiencing. If we accept that the brain has to create its own simulation in order for us to experience something, there's no reason why the simulation can't bias our perception of when we chose to act. So we act out of a larger, richer self, but experience ourselves as acting from a narrowly defined self-aware self with no real privileged insight into the mental processes behind it.This may well be the best discussion of conscious awareness yet presented in a generally readable form. But it does have some glaring weaknesses. The author takes great pains to build this model of conscious awareness from the ground up, but then applies it in a brief and haphazard manner to all sorts of things that deserve much more thought, such as religion, hypnosis, dreams, and so on. Even with the few weaknesses, the case made for the author's view of conscious awareness is both compelling and us

today's Godel, Escher, Bach

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

An invaluable book analyzing consciousness from the prespective of information theory. Author unites physics, theory of computation & neuroscience through, still widely misunderstood, information theory. In a very clear, and at times entertaining language, the author delivers to the reader an epitome of exceptional quality. Beautiful and simple idea of discarding the information is fundamental to our understanding of the world and ourselves.