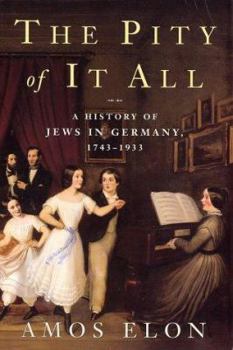

The Pity of It All: A History of the Jews in Germany, 1743-1933

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The Pity of It All is a passionate and poignant history of German Jews, tracing the journey of a people and their culture from the mid eighteenth century to the eve of the Third Reich. As it is... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0805059644

ISBN13:9780805059649

Release Date:November 2002

Publisher:Metropolitan Books

Length:464 Pages

Weight:1.78 lbs.

Dimensions:1.4" x 6.4" x 9.5"

Related Subjects

European History The Holocaust Biography Europe Germany History Modern (16th-21st Centuries) WorldCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

A history of the theological-political problem.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

There are many strengths to this book- one of the main strengths is the variety of uses that it has. It's obvious purpose is to relate the history of German Jews from the rise of the Enlightenment to the rise to power of the Nazi party. But it serves other purposes as well. I came to it for an understanding of the intellectual background of both Leo Strauss and Hannah Arendt. It could serve as background reading for anyone interested in Einstein, Benjamin, Adorno, Horkheimer, Freud, Adler, Fromm, Marcuse, Mannheim, Popper, Bernstein, Cassirer, Schoenberg, Husserl, Weill, among other German-Jewish intellectuals to numerous to mention. Which brings me to my third purpose. I have never read anything that made me realize just how badly Germany damaged itself intellectually during the rise of the Nazis. It serves as the primary example of politically ripping your heart out because your brain commands it. Who knows what the country could have become if it had embraced it Jewish citizens? Finally, for me, this book makes me understand why Zionism became such a political force. At some point, when you are treated like the Jewish citizens of Germany were, what else can you do? Elon makes it clear that their suffering began long before the twentieth century. I want to talk about Elon's methodology. His book is basically a series of well chosen capsule biographies of prominent German Jews whose lives and struggles for emancipation and assimilation serve as to tell the stories of all German Jews. His focuses on people like Moses Mendelssohn, Rahel Varnhagen, Heinrich Heine, Ludwig Borne, Ludwig Bamberger, Gershon Bleichroder and Walter Rathenau. Along with this main biographies are several dozens of shorter ones. Elon then surrounds these stories with a certain amount of sociological history (two of his favorite statistics are to look at the rate of conversions from Judaism to Christianity and the rate of intermarriage). He tries to relate those stats to larger historical events. Finally, he also uses a bit of cultural history,e.g., he sees Goethe's idea of Bildung as having an even larger impact on German Jews than on the rest of the German population. This methodological approach to his story has some drawbacks. Non-intellectual and/or lower class German Jews remain in the background in Elon's book. I am not sure how this could be avoided. There may be some sort of historical record that would tell us more about this part of the population but it is hard to imagine what that record would be. It is also easy to imagine that life for the poorer and less literate parts of the German Jewish population would have been even worse. Most careers were closed to them, all civil and political rights were denied to them and many times, entire cities or districts were closed to them. In most cities they lived in ghettos and were not allowed to go out into the rest of the city on Sundays or Christian holidays. Elon also makes it clear that in many ways, Germany was one

The Failed Secular Messianic Age of the German Jews

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Belief in the coming of the Messiah and a Messianic era of world peace is an integral part of traditional Judaism. Even secularized Jews, starting with Moses Mendelssohn and others, transfer this belief into an attempt to create a worldly utopia in the here and now while abandoning traditional Jewish observance. This explains why various universalist, utopian philosophies, such as Marxism, attracts secular Jews. Similarly, attempts to create an improved "Reform" Judaism, or a quasi-universalist Socialist Zionism attracted Jews who had abandoned belief in the Jewish religious tradition. Amos Elon, a Jew of this type, in this outstanding book, looks back at what seemed at the time, the most successful attempt of the Jews to shed their supposedly "parochial" traditions and to assimilate into what looked like a vital culture, Germany of the 19th and early 20th century which had such a flowering of music, literature, art, science and industry in which Jews played such a major role. Although most Jews abandoned religious tradition in the period, moving upward in the social and economic mileu of Germany, and felt that they were as German as any non-Jewish German, especially after having fought as good patriots in the wars of the 1870 and 1914-1918, the whole edifice of German Jewish assimilation came crashing down, dragging much of Europe into the abyss with it. Many Jews came into prominence in the highest levels of German society and politics, even into the Kaiser's entourage, and yet, when the crunch came with the defeat in 1918, the Kaiser and others blamed "the Jews" for the defeat, even though the Jews were the most loyal of all Germans. As Elon points out, many in Europe admired or feared the Germans, only the Jews loved them. And this love was totally unrequited, as the Germans, as a people, decided that the Jews were responsible for all their problems and that the Jews would have to be annihilated, even if it meant the destruction of their own country in the process. Elon describes well the adoption of the "kulturreligion", the religion of culture that the German Jews adopted with their almost fanatical devotion to music, literature, art and philosophy, and their blind, fanatical patriotism that burst out in 1914 when even many who would later claim to be pacifists such as Martin Buber expressed bloodthirsty enthusiasm for war and German aggression. However, I don't agree with Elon's assertion at the end of the book that Hitler and the Holocaust "weren't inevitable" since he claims that Hitler came to power only through a shabby political deal and not through "irresistable historical forces". All the accounts I read of the period by Germans who were around at the time said most people, especially the young, felt that Germany's future was "either Red or Brown" (i.e. Communist or Nazi) and that democracy was discredited. What is especially interesting is how Elon is expressing his own longing for such a secular messianic era. Once an ardent Zio

The Failed Secular Jewish Messianic Era in Germany

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Belief in the coming of the Messiah and a Messianic era of world peace is an integral part of traditional Judaism. Even secularized Jews, starting with Moses Mendelssohn and others, transfer this belief into an attempt to create a worldly utopia in the here and now while abandoning traditional Jewish observance. This explains why various universalist, utopian philosophies, such as Marxism, attracts secular Jews. Similarly, attempts to create an improved "Reform" Judaism, or a quasi-universalist Socialist Zionism attracted Jews who had abandoned belief in the Jewish religious tradition. Amos Elon, a Jew of this type, in this outstanding book, looks back at what seemed at the time, the most successful attempt of the Jews to shed their supposedly "parochial" traditions and to assimilate into what looked like a vital culture, Germany of the 19th and early 20th century which had such a flowering of music, literature, art, science and industry in which Jews played such a major role. Although most Jews abandoned religious tradition in the period, moving upward in the social and economic mileu of Germany, and felt that they were as German as any non-Jewish German, especially after having fought as good patriots in the wars of the 1870 and 1914-1918, the whole edifice of German Jewish assimilation came crashing down, dragging much of Europe into the abyss with it. Many Jews came into prominence in the highest levels of German society and politics, even into the Kaiser's entourage, and yet, when the crunch came with the defeat in 1918, the Kaiser and others blamed "the Jews" for the defeat, even though the Jews were the most loyal of all Germans. As Elon points out, many in Europe admired or feared the Germans, only the Jews loved them. And this love was totally unrequited, as the Germans, as a people, decided that the Jews were responsible for all their problems and that the Jews would have to be annihilated, even if it meant the destruction of their own country in the process. Elon describes well the adoption of the "kulturreligion", the religion of culture that the German Jews adopted with their almost fanatical devotion to music, literature, art and philosophy, and their blind, fanatical patriotism that burst out in 1914 when even many who would later claim to be pacifists such as Martin Buber expressed bloodthirsty enthusiasm for war and German aggression. What is especially interesting is how Elon is expressing his own longing for such a secular messianic era. Once an ardent Zionist, who thought a similar Israeli society based on a similar "kulturreligion" would develop in Israel and people like him would be revered as national "philosophers", he, to his horror, saw the revival of traditional Jewish religious observance, bringing him to the decision earlier this year to leave Israel for good. As he stated in a newspaper interview, he used to be able to call the Prime Minister of Israel to arrange a personal meeting, but today, the political el

Outstanding, Compelling History of Jews in Germany

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Too often the history of Jews in Germany is portrayed as beginning with the Weimar Republic and ending with the Holocaust. This German-Jewish history begins much earlier, in 1743, and ends before the Third Reich has obliterated the German Jewish community. It is a sobering tale. The story of Jews in Germany is essentially one of a long unrequited love affair. From decade to decade, and century to century, the Jews featured in this book wanted nothing more than to be Germans. They did everything in their power to demonstrate their "Germanness," from eagerly volunteering to fight for Germany in the Franco-Prussian and First World Wars, to making important scientific discoveries (10 German Jews won Nobel prizes in science), to financing various principalities, to writing great German poetry. A good many Jews were even willing to convert to Christianity in order to blend in, or to be able to practice their professions. The rulers of various German states (there was no united "Germany" until 1871) cynically used Jews as a source of funds, allowed them minimal rights, and expelled or denied them advancement at whim. Still, the people who refused to call themselves "German Jews" ("We are German citizens of the Jewish faith!") kept abasing themselves to join this society. One wonders why. One reason is that Germany did have a lot to offer -- it was a leader in philosophy, science, music and art. A historian visiting Berlin in the 1970s said that the 20th Century could have been the German century. Another reason is that as bad as Germany was, it treated its Jews better than many other places in Europe, particularly Russia. And in the Weimar Era, German Jews were represented at all levels of government: the Foreign Minister was a Jew, as was the head of a short-lived socialist government in Bavaria. Jews were leaders in science, architecture, music and theatre. German Jews even believed that they were better off than their co-religionists in the United States,where Jews were excluded from many neighborhoods and jobs, and Ivy League schools had quotas. (Of course, there is nothing in American Jewish history remotely similar to the German religious exclusions, or, worse still, "Hep, Hep!" riots.) The major flaw in this book is that while it discusses the impact of German Jews on Germany, it gives short shrift to the impact of German Jews on Jewish life, and neglects the more religious Jews altogether. The omission of Samson Raphael Hirsch, one of the greatest Orthodox leaders of all time, is inexplicable. The philosophy of "Torah im Derech Eretz," i.e., that Jews should simultaneously study Torah and be conversant with modern culture and thought, is the foundation of the Modern Orthodox movement -- and it started in Germany. It is sometimes difficult to wade through long non-fiction books, especially history, but not this one. The book grabs you in the beginning and never lags. (Not only is Elon a great writer, but he has made the not-incons

One of the best works on German Jewry I've read

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

"The Pity of it All" is on par with Peter Gay's works in terms of the elegance of the writing and the delicate evocation of its period. Elon's work is thoroughly researched but does not bury its reader in needless detail the way so many historians, eager to show off their research, do. Nor does Elon wring his hands over the genuinely difficult question: "How could Germany's Jews not have known they were hurtling torward disaster?" Elon answers this question, in a sense, by avoiding it and instead carefully evoking a very particular place and time. Once he has done that, the question evaporates--or, at least, no longer seems separable from understanding that place and time. Elon's work is studded with mini-biographies of important historical players (Moses Mendelsohn, Walter Rathenau, Albert Einstein, Chaim Weizmann, Hannah Arendt, to name just a few), which keep the reader's interest; they are empathetic portrayals but never hagiographical. Overall, a great read.