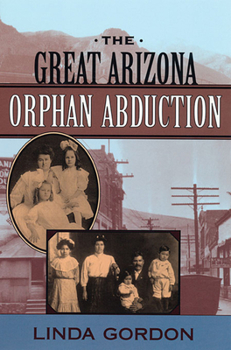

The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 1904, New York nuns brought forty Irish orphans to a remote Arizona mining camp, to be placed with Catholic families. The Catholic families were Mexican, as was the majority of the population. Soon the town's Anglos, furious at this "interracial" transgression, formed a vigilante squad that kidnapped the children and nearly lynched the nuns and the local priest. The Catholic Church sued to get its wards back, but all the courts, including the...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:067400535X

ISBN13:9780674005358

Release Date:April 2001

Publisher:Harvard University Press

Length:432 Pages

Weight:1.29 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.2" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

astonishing awakening

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This is one of the best history books I have ever read. Not only does it focus on a little known, little discussed part of history...the selling of orphans, it also sheds light on the cultural factors that allowed this to happen. I have passed this book on to so many friends that I have had to purchase extra copies to continue to do so. The author has an easy style that could almost lull you into thinking you are reading a novel. Well, given the facts in this wonderful book, it is one of those books that are often talked about "If someone wrote a book about this no one would believe it." Thank you Linda Gordon. I hope you have more books like this in progress. I am a real fan.

Imagine That

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Linda Gordon takes a small story out of the old southwest using court records, oral histories, interviews, and hospital records to create a highly readable and provocative work of American history. She recounts the half-legend of the Arizona orphan abduction to reveal what it meant to be human a hundred years ago. It was a time and place of nation-building and evolving standards of citizenship. During that colonizing period, dominated by self appointed "civilizers," racial attitudes allowed a mob to kidnap infants at gunpoint only to have the Supreme Court grant the perpetrators custody. The Euro-Americans did not want Mexican-looking people to gain any whiteness in the form of the foundlings and thereby diminish their status. Today it seems like an outrage akin to Plessy v. Fergusson. Against a backdrop of the smoldering mountains of oozing slag, Gordon describes how the eastern nuns fought the western WASPY-neighbors-from-hell in an effort place their charges in good catholic homes. This story heightens the contrast of the blurred lines of identity: gender, religion, politics, nationality, class, regional identity, group and subgroup, and most of all, race. These lines, like the borderlands themselves, are never clear and fixed. They shift in and out of focus, but they nevertheless affect the concrete balance of power between labor and capital, men and women, the genteel and the half-breed, the wicked and the good, the white and the non-white other. Gordon's thesis is that fickle notions of race dictate status, from the Irish Catholic birth mothers to mine workers. Race was a badge of rank for courtroom and lynch mob alike. In an age of imperialism and social Darwinism race determined one's place, trumping class, religion, education and merit. It determined everything from social mobility to one's worthiness to adopt. Those who were blind to the shifting hierarchy of racial identity were destined to lose. Industrialists manipulated race to undermine worker solidarity in their company town. It trapped the Mexicans in a degrading Catch-22; they were paid less and therefore tainted by imposed poverty. Denied a chance to shower and change clothes, they were condemned as filthy creatures. The unspoken understanding between Anglo laborers and mine owners kept Mexican wages low. The same quality that makes Gordon's so engaging might drive a doctrinaire historian crazy. With her imagination Gordon fills in the gaps that could not be documented. But I, as a graduate student and a lover of good historical writing, can appreciate her style when she says, "no doubt they (the vigilante town folk) were cleaning their rifles." She can't really know that but it rings true and brings the story to life.

Excellent microhistory

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Linda Gordon's "The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction" tells one small story in order to examine a far larger one. In 1904 the Catholic sisters in the employ of the New York Foundling Hospital attempted to place several white, Catholic orphans with Mexican families in the mining towns of Clifton-Morenci, Arizona. The white Protestant residents in the towns objected strenuously to the placements, and joined together to steal the children away from the prospective Mexican parents. Appalled by the scenes of mob activity and the threats made on their lives, as well as the idea of Protestants adopting Catholic children, the Foundling Hospital sued in court to retrieve the orphans. The case first went to the Arizona Territorial Supreme Court before moving on to the United States Supreme Court, which ultimately gave permanent custody of the children to the Arizona whites. This story as told by the author--an excellent example of microhistorical research--provides the impetus to pursue a host of larger subjects involving labor issues, gender, class, mob violence, and child welfare. The overarching theme is race relations. To understand the orphan imbroglio, Gordon contends, one must understand the racial attitudes whites held about Mexicans. In the late nineteenth century, when Anglos were a weak minority trying to establish themselves in the Southwest, Mexicans could more or less stand on an equal footing with many of the white laborers and settlers. What changed? The arrival of more white settlers increased the power of Anglos. Too, the implementation of large-scale industry--here, the consolidation of individual copper mines--as the sole means of employment in the region brought about an unspoken agreement between Anglo laborers and mine owners to keep Mexican wages low. Finally, the consolidation of white political power helped to disenfranchise Hispanic laborers. Underpinning these issues was an unchanging opinion of Mexicans. Whites saw them as dirty, itinerant immigrants whose presence threatened to drive down wages. While itinerancy was a reality in the late nineteenth century, by 1904 much of the Mexican community had settled down. Many of the mineworkers lived in Clifton-Morenci with their families and children, were productive residents, and usually only returned to Mexico for brief visits. The orphans from New York, therefore, stepped into a complicated racial situation, a situation further exacerbated by Anglo women. They were the ones who first noticed the nuns giving children to Mexican families, and they brought their husbands into the fray in short order by promoting a vigilante solution. Gordon sees this aspect of the orphan incident as a prime example of how women could step beyond their traditional boundaries in order to take part in the public sphere normally closed to them. And this applied to both Mexican and Anglo women, as it was Hispanic women who agreed to adopt the children and Anglo women who fought to take them away. Mexican

Excellent examination of the evolution of race in US history

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Ms. Gordon has told in a compelling, exciting manner the tragic story of how 40 orphans became a pawn, first in New York's reform movement, and then in the southwest labor struggles.However, her book goes far beyond this simple story, by using it as a springboard for an examination of the evolving concept of "race" in american history, and how the concept of race was used in different ways, at different times--tied to economic, religious and gender issuses which prevailed at diiferent times in different places.The central "action" in Ms. Gordon's narrative is not, as several reviewers seemed to think, the abduction of the orphans. It is the transformation of the orphans from "Irish"--a despised minority in New York--into "White"--a powerful minority in Arizona, as they took their 2,000 mile train ride to their new adopted homes.The only reason that I did not rate this book five stars is because Ms. Gordon first does a very good job explaining the paucity of evidence for the actual abduction--poor people tend not to leave historical records. However, she periodically leaps beyond this limited records into wild speculation (which may well be correct, but certainly is not supported by her evidence), all without acknowledging the contradiction.All in all, well worth the read for anyone who is interested in the role race has played in american history--which ought to be all of us.

A Stunning Look at Southwestern History

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Seemingly small incidents can offer large insights into the process of social change. Linda Gordon, perhaps our country's leading historian of women, has taken a largely forgotten episode in which 40 Irish orphans were placed with Mexican families in a remote Arizona mining town and made it a window into some of the most important themes in the history of the 20th century Southwest. In her book we relive the human meaning of migration for thousands of Mexicans and we see the role of race and gender in the creation of a colonial economy in the Southwest. Above all, her book offers a valuable lesson for our time. She shows how an earlier ideology of family values was misused and abused, and harmed the interests of the very children it was supposed to help.