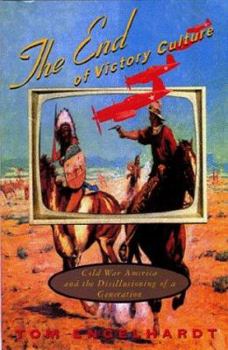

End of Victory Culture

(Part of the Culture and Politics in the Cold War and Beyond Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In a substantial new afterword to his classic account of the collapse of American triumphalism in the wake of World War II, Tom Engelhardt carries that story into the twenty-first century. He explores... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:1558491333

ISBN13:9781558491335

Release Date:January 1998

Publisher:University of Massachusetts Press

Length:360 Pages

Weight:1.30 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.2" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Book Review: "The End of Victory Culture : Cold War America and the Disillusioning of a Generation"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

American "triumphalism" and the American "war story" began its decline after WWII and collapsed completely after Vietnam (or so the author thought). The victory myth is constructed out of an America history that has its roots in the Puritan struggle. The US had always fought against the evil oppressors of freedom, democracy, and the freedom of peaceful worship. The myth of American triumph was part of 1950s "boy culture" and was depicted on screen in the justifiable slaughter of Indians on the western frontier; cowboys and /or Cavalrymen who rescued families and females from savages; science-fiction and vengeance movies, and eventually in galactic villians and Evil Empires. War stories and movies consumed by Baby Boomers vindicated the annihilation of (usually non-white but always non-American) villains. Central to the maintenance of the victory culture in American is the "war story" a tale in which there is an evil Other who threatens the United States. Contributing to the end of victory culture was the almost immediate reevaluation of the atomic bombing of Japan after WWII; an event that left the United States looking more terrifying than protective . The Cold War followed the euphoric victory of WWII . In the Cold War there was no victory or defeat; and the enemy and self became blurred and threatened to merge. Many of the villains in the Cold War were other Americans; rather than victory, the US sought containment. Then came Korea, a failed police action, better off forgotten. The Vietnam War was a disaster. Even the president lost enthusiasm for a battle where there appeared to be no definable enemy. Even the sacred cowboy was attacked as racist during the d?nouement of the victory culture. New westerns depicted sociopathic bad guys in cowboy hats rampaging around the West hunting down innocent Indians. In the late 1960s, even military toys were transformed into action figures. "Boy culture" was not recaptured until Ronald Reagan appeared on the scene with his Star Wars rhetoric. George H. W. Bush seized on the opportunity to eliminate the evil dictator Saddam Hussein; only to have his efforts to win a "war to re-establish war, American style" and capture the bad guy fail. Engelhardt is an active journalist and writer who was surprised in 2000 when the United States elected George W. Bush President. Geroge W. Bush, he says, is a man "who had stayed way too long in those dark movie theaters" watching cowboys and Indians; a man who managed to evade both sides of the Vietnam War debate; a man who glories in the victory clture and wants to relive a period in American history when bugles blared, crowds cheered, and flags waved. In The End of Victory Culture Engelhardt failed to predict that 2005 would see a US President whose dream is to "dress up like G.I. Joe, [and] appear in front of massed ranks of soldiers chanting "hoo-rah," and assure the crowd he was going to bring `em back dead or alive (tomdispatch.co

one of my favorites...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

With the outcome in Iraq still uncertain more than 3 years after the U.S. led invasion, many people have blamed the media for not being critical enough at the outset of the war. Additionally, as the war rages on, comparisons to Vietnam are becoming especially noticeable as a growing number of people continue to question our involvement in Iraq. These two relatively recent phenomena of questioning the media's role in wartime and the tendency for U.S citizens to be skeptical of their government during war took root during the Vietnam war. According to Tom Englehardt in "The End of Victory Culture," prior to Vietnam the media played a key role in perpetuating the idea of a noble and just United States battling savages of color including Native Americans and Japanese soldiers in World War II. The public eagerly imbibed this "victory culture," regularly attending movies featuring John Wayne defending America by battling Indians; playing games like "cowboys and indians;" and reading cartoons featuring horribly caricatured Japanese and Chinese soldiers, never questioning the integrity of the government or doubting United States policies. A seismic shift occured during Vietnam when, for the first time, Americans became especially frustrated over a war that could no longer be justified by statements from the President. Demonstrations raged throughout the country as the once sacred tenants of U.S. heroism and leadership were shattered. During this time, the media's role transformed as well. Rather than mindlessly trumpeting American nobility, the media worked doggedly to unearth the truth. David Halberstam's coining of the term "quagmire" when referring to war and Morley Saffert's piece revealing the horrible killings of helpless Vietnamese villagers are just two examples that Englehardt cites. Although accounts from Vietnam and World War II comprise the bulk of Englehardt's thesis, he provides copious examples of the movies and excerpts from television programs when talking about the 1980's in an effort to further demonstrate the dismantling of the "victory culture." Brilliantly written and extremely well documented, Englehardt has written a gem of a book that remains as relevant today as it was 11 years ago when it was first published.

A different perspective on post-war culture and history

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Tom Engelhardt's dense but throughly readable cultural history presents the past fifty-six years of American history as an investigation of narrative. A common theme in analysis of nationalism and nationality is the concept of an historical narrative that members of a nationality look to for explaining their present position within their world. Engelhardt investigates a time period that saw, as he argues, a violent uprooting and reconfiguration of the American cultural narrative. This narrative makes use of a wide ranging set of metpahors and images, such as the frontier and its mythology of American innocence, that have helped Americans understand their position within a complex and ever changing world. World War II provided the last war in which the innocence of America was posited with little debate (although the dropping of the atom bomb indeed challenged this innocence). The beginning of the cold war and military endeavors in Korea and Viet Nam saw a gradual erroding of this narrative of innocence. As the enemy became harder to identify, at times even looking like ourselves in the case of anti-communism, the moral clarity and absolute innocence of American military actions disolved. Engelhardt takes a sweeping view of the last half-century of American history and tracks the profound shift in narrative and cultural understanding that we are still dealing with. It would be interesting to see what Engelhardt would say about September 11th. I would argue it has restored much of America's innocence, allowing us to attack Iraq with little domestic objection. Engelhardt writes with an engaging voice helping to make what could be a tedious read quite enjoyable. At times his ideas can be difficult to connect, making this a book to be tackled as quickly as possible so that the plethora of information and full scope of the analysis can be engaged without loosing what was written in earlier pages. Do not expect any sort of 'traditional' work of history. This is for the students of American culture and anyone interested in the intricacies and complexities of the American identity. When you read this book, to a large extent you are learning about yourself.

A story of "we" against "they"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Tom Engelhardt's The End Of Victory Culture is a thought-provoking, historical look at how the concept of defeating a less-than-human enemy was part of American culture. Ingrained in that was the mission to defeat that enemy. The trouble was, the enemy was human, be they the Native Americans the colonists and later the American government displaced. We also had this mindset that we were always on the right and they were always wrong, therefore, they had to be defeated.One element was to exaggerate the atrocities committed, meaning that yeah, some of it happened, but not in the large scale depicted by the white leaders to drive home the point that we had to kill these unholy, ungodly, . Colonist Mary Rowlandson's accounts on her captivity and the massacre she survived was the archetypal demonizing of the "enemy."Victory culture nestled itself cozily in new visual media--the movies and television. Basically, the enemy performed some horrible atrocity on innocent whites, and it was up to the heroes to punish the enemy. The enemy would be defeated, more often than not killed, and everybody would live happily ever after. Straight and simple. It was in straight black-and-white (the issues as well as the early programs before colour TV and film came into being).Engelhardt argues that between 1945 and 1975, the ends of WW2 and Vietnam respectively, that victory culture endedPearl Harbor gave plenty of opportunity to dehumanize the Japanese as an enemy, along with Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.The Cold War was where it all went into overdrive. The Communists were now the enemy, and that paranoid ideological struggle into the unknown carried through not only into Korea and Vietnam, but into movies, TV shows (Twilight Zone), comic books (Tales From The Crypt, MAD), and even toys (GI Joe).A new dynamic also came, of the enemy hiding behind some citadel or bunker, such as the Forbidden City or Kremlin, with only large posters of the leader representing the human face of the enemy. Thus the enemy couldn't be destroyed.Vietnam demonstrated once and for all that we were fallible, and for a while, we were in a funk. And with My Lai, WE became the massacring enemy, the Vietnamese the colonists. The concept of victory culture was turned on its head with that event. And think about it: we lost Vietnam for the same reasons the British lost the American War for Independence. History has come full circle to America.This book came out in 1995, and early on in the book, Engelhardt makes a well-worn but important point: "with the end of the Cold War and the loss of the enemy, American culture has entered a period of crisis that raises profound questions about national purpose and identity." Ponder that passage, and what's going on today in the world.The main thing to ask today is, do we really need to have an enemy and a war to unite the people together? Peace and harmony can do the same thing. We do not need victory-for-one-side culture anymore. W

Welcome To The Twilight Zone?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

"Is there an imaginable 'America' without enemies and without the story of their slaughter and our triumph?" (p. 15) This is the question at the heart of Engelhardt's remarkable blending of popular culture studies and military history. In its outline, the thesis is straightforward: a long-established racially-exclusive national myth of bloody but righteous American retaliation to treacherous foes unraveled in the three decades after World War II. The new limited war strategies of the nuclear age forced awkward "containments" of this myth. The battlefields of Asia and, in particular, of Vietnam, led to "reversals," in which increasing numbers of Americans came to conclude that the familiar patterns that had helped to define national identity had been turned upside down. It is in the details of his argument that the author is at his best, making unexpected but genuine links between Mr. X (George Kennan) and Malcolm X; between the Mary Rowlandson captivity narrative of 1675 and the My Lai massacre of 1968; between the Strategic Air Command and Rod Serling; between V-for-victory signs and peace signs; between Chewbacca and Edward Teller; between Charles Manson and 1950s comic book culture. Engelhardt brilliantly explores the complex connections between the games of American children and the broader national culture. That Engelhardt himself, born in 1944, was embedded in the post-war childhood culture is simultaneously a source of the book's greatest strengths and its greatest weaknesses. On the positive side, he draws upon autobiographical reminiscence in an understated and thoughtful manner. At times, however, he risks confusing the disillusioning of a generation (his own) with the end of what he calls "victory culture." The myth of American innocence is indeed a powerful one, but Engelhardt perhaps exaggerates its coherence and pull in the pre-December 7, 1941 world. The boundary lines of any national story are always fluid, and it was not only the Civil War that tested these boundaries in earlier eras. I also wonder whether it may be too soon to conduct post-mortems on victory culture. Engelhardt sees efforts to reinvigorate the tales of American exceptionalism in the post-Vietnam decades as tortured and ineffective. His comments about yellow ribbons, POWs, and new myths of victimization are intriguing, but my sense is that the metaphorical circling of the wagons will continue. Americans are not yet ready to see themselves as part of a vast human comedy.