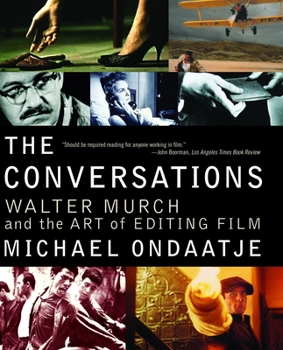

The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The Conversations is a treasure, essential for any lover or student of film, and a rare, intimate glimpse into the worlds of two accomplished artists who share a great passion for film and storytelling, and whose knowledge and love of the crafts of writing and film shine through. It was on the set of the movie adaptation of his Booker Prize-winning novel, The English Patient, that Michael Ondaatje met the master film and...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0375709827

ISBN13:9780375709821

Release Date:October 2004

Publisher:Knopf Publishing Group

Length:339 Pages

Weight:0.70 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 7.0" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

"One Art"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Walter Murch may be the greatest film editor alive, having cut classic works by Coppola (THE CONVERSATION, THE GODFATHER PARTS I, II, and III, APOCALYPSE NOW, THE RAIN PEOPLE), Minghella ( THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY, COLD MOUNTAIN), Kaufman (THE UNBEARABLE LIGHTNESS OF BEING) and Zimmermann (JULIA). The novelist Michael Ondaatje, whose best-known novel THE ENGLISH PATIENT was adapted by Anthony Minghella into another a film cut by Murch, had the fine idea of sitting down for a series of conversations with Murch to ask him about his little-understood, important, and intelligent art form. The result is one of the greatest series of extended conversations on film since Truffaut's interviews with Hitchcock. Part of the pleasure of the book is getting not only to see Murch's complex work described but also getting to know him as a personality: considered one of the most intelligent men in Hollywood, he comes across not only as exceptionally erudite but also unpretentious and honest. Ondaatje may be the ideal interlocutor for Murch because he is so beautiufully versed in film history and in Murch's work; his many asides about his own writings may allow him to come across at times as a bit self-enamoured, but they do allow the reader the multiple pleasure of having a major figure in world literature give insights into his own work as we also hear about Murch's. One of the best delights the book offers is ample illustrations of the examples Murch and Ondaatje discuss, which are drawn from literature and the other arts and humanities as much as they are from film: one of the best is when the book offers side by side comparisons of the first draft and final version of Elizabeth Bishop's great villanelle "One Art," which is itself a celebration of the art of editing. It is rare to see a non-academic book about film that takes its readers' intelligence for granted. As such, it is genuinely a book everyone seriously interested in film should own.

Finally NOT about editing programs!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This book is about the insights and experiences around editing, about a lifestyle and philosophy of editing. I love the many insights and Murch is good narrator. Sometimes Michael is talking too much, but on the other hand it's a conversation, not an interview... I love this book, as it creates great mood and ambience, I read it in a single (long) shot. And then again.

The Art and Science of Film Editing From a True Master

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

The film editor is the great unsung hero of the filmmaking process. After all, during the annual Oscar ceremony, the award for Best Film Editing seems to be hidden away between bad production numbers and some indecipherable technical award. As directors like Francis Ford Coppola and Anthony Minghella constantly receive praise for their creative visions, it is obviously the film editor's onerous task to make sense of that vision and capture the key moments and sounds that define it. Film editor and sound designer par excellence, Walter Murch, is the subject of this endlessly fascinating book, which chronicles a series of five extensive conversations he had with Michael Ondaatje, author of "The English Patient". They met on the set of that film, one of many fine films Murch has edited, and Ondaatje was so struck by his personality and methods that he decided to write this book. In fact, Ondaatje was bowled over by how Murch could draw lines connecting the most disparate things in the cosmos: philosophy, technology, science, music, literature, art, languages, sound theory. Murch can locate the impulse of a film in the symphonies of Beethoven or in the way he views painting and architecture. He knows of what he speaks as his track record is very impressive - "Apocalypse Now", all three parts of "The Godfather", "American Graffiti", "Julia", "The Unbearable Lightness of Being", "The Talented Mr. Ripley", and the list goes on. This intriguing book also explores the dynamic relationship between film editing and writing, which means Ondaatje is in a unique position to provide insight into his own methods. It becomes clear that Murch's descriptions of his editing offer Ondaatje new ways of understanding his own work as a novelist, and much of the pleasure derived from the book comes from Ondaatje's self-discovery process. Murch convincingly presents himself as both a physicist and a mathematician of cinema and suggests that we are in a prehistoric period, and that over time, we will eventually develop a system of notation for film much like musical notes. He sees it as his own destiny to uncover the underlying mathematics of cinema. Of course, Ondaatje provides perspectives of the filmmakers with whom Murch has worked extensively, providing accounts of Murch's importance in Hollywood by such figures as Coppola and George Lucas. Some films understandably get more attention than others. There is a lot of discourse on "The Conversation" and "Apocalypse Now", including the Redux version, as well as the "Godfather" trilogy, including his re-edit to make it one giant epic. Lots of revelations come out in these discussions. For example, one can now finally understand that Robert Duvall's absence (due to pay demands) is to blame for the lackluster "Godfather Part III" since the initial vision was to focus on the death of Tom Hagen, much as it was on the killings of Sonny in Part I and Fredo in Part II. He also has some interesting insight in the recutting and re

Credit due

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Film directors are like Napoleon, all-powerful and usually vertically challenged. "But even Napoleon needed his marshals," says Michael Ondaatje in this book, a series of conversations with leading US film editor Walter Murch. Although just one of hundreds of names seen in the credits when the crowd is filing out of the cinema, the film editor is crucial to turning the director's vision into a viewable reality. The film editor - and many of the greats have been women, like Anne Coates (Lawrence of Arabia, Out of Sight) or Thelma Schoonmaker (longtime Scorsese editor) - is one of the unsung heroes of the form; they can shape the mood, create the pace, make the story work. It was when Ondaatje's novel The English Patient was being turned into a film that he befriended Murch, an intellectual as well as a craftsman. Murch's talent helped Francis Ford Coppola shape some of the most important American movies of the 1970s: the first two Godfather films, Apocalypse Now, and 1974's The Conversation. The latter gives this book its title, and was recently restored. Its very subject matter concentrates the mind on the aural side of film-making; it's about a sound engineer (Gene Hackman) and specialist in surveillance work who hears of a murder plot. Filmed on a low budget between the first two Godfathers, it encapsulates the issues Murch faces in his job. A simple matter like the clothing a character wears can make the editor's job easy or impossible. If the costume department insists on strutting its stuff, dressing the lead in a variety of outfits, that limits what an editor can do if the story has to be reconstructed at the editing desk. Murch came to editing after being a sound editor, and he expounds on the use of music and sound in movies. His work on American Graffiti revolutionised the use of pop in movies. Now, most films have a relentless soundtrack, either telegraphing narrative punches, crassly manipulating the emotions, or inappropriately creating a merchandising tie-in. "Most movies use music the way athletes use steroids," says Murch. "It gives you an edge, it gives you speed, but it's unhealthy for the organism in the long run." There's nothing subtle about mainstream movie making now, and The Conversations returns the audience to the basic craft, inviting them in so their experience is enhanced. It's the best book about filmmaking since Francois Truffaut's similarly illuminating Hitchcock.

Inside a unique mind (actually, two of them)

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I don't usually like Q & A-style interviews, but this book is a notable exception because it's more like eavesdropping on a private conversation between two very savvy colleagues. Murch has some original and intriguing things to say about the ways he approaches his art (like theorizing that movie music reinforces an existing emotion--rather than inspiring one). Here's looking forward to his next book--the one in which he posits his notational scheme for cinema. It sounds like a crackpot idea, rather like that musical I wisely never wrote in which each instrument corresponded to a different bodily function. I suspect Murch can deliver on his dream, if anyone can.