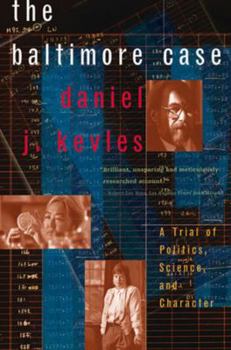

The Baltimore Case: A Trial of Politics, Science, and Character

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

David Baltimore won the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1975. Known as a wunderkind in the field of immunology, he rose quickly through the ranks of the scientific community to become the president of the distinguished Rockefeller University. Less than a year and a half later, Baltimore resigned from his presidency, citing the personal toll of fighting a long battle over an allegedly fraudulent paper he had collaborated on in 1986 while at MIT. From the...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0393319709

ISBN13:9780393319705

Release Date:January 2000

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:510 Pages

Weight:1.40 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 6.1" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A GOOD SCIENCE WHODUNIT

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

For me The Baltimore Case was edifying and a pleasure to read. I recommend it highly to anyone like myself who followed desultorily the media's presentation of the proceedings before the Congressional Subcommittee as putting "Science on Trial," but without any grasp of the underlying science. And I agree with the previous reviewers' conclusion that the book is too long although I attribute its length to the author's commitment to thoroughness. I finished The Baltimore Case feeling I'd learned a lot about viral research in an academic setting, the role of personality conflicts in this research, and the editorial practices of scientific journals like Cell. (Excuse me for not saying more about the political, scientific, and personal disputes that the book so fascinatingly details, but to my mind they are commendably covered in the other reviews.) I especially admired the author's sustained treatment of the central story as a murder mystery with no murderer and everyone the victims, as well as his clear presentation of the underlying scientific facts. Professor Kevles did a very impressive job.

Will the politicans vanquish the scientists?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

As an engineer by training and profession, this book really makes my blood boil. It's basically the true story of some scientists at MIT who publish a paper on immunology. A student of one of the professors challenges that some of the data in the paper was faked, and an epic of Phyrric proportions ensues. In the 10 years that this book covers, scientific careers are ruined, researchers are vilified in the media and in the court of public opinion, and (most troubling of all to me) our elected officials engage in a witch hunt of completely innocent scientists. In particular, Senator John Dingell (Michigan) and his staff are revealed as complete devils; the author has thoroughly documented and footnoted the evidence in the case, so there is really little doubt that Mr. Dingell is as pernicious as he is portrayed in this book. Unfortunately, Mr. Dingell is still a senator to this day and no doubt is still out "to get" the scientists involved. Fortunately for science (and society), history has proven the scientists involved innocent and they have all been restored to preeminent positions in the scientific community.Be forewarned that this is quite a tomb, weighing in at hundreds of pages of meaty scientific and political reading. At times, I contemplated giving up on it, but as the story unfolded, I wanted to see just how far this tragic comedy would unfold. The subject matter (immunology) is far removed from the layperson and I found myself at times not understanding the concepts fully. Luckily, this book is more about the sociopolitical ramifications of the science, and thus not understanding the science does not detract from the novel.

Science and the Politics of Science

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Kevles has written a masterful account of the Baltimore Case (Imanishi-Kari Case might be better). I can only second the glowing reviews already on this page. A few things that might interest the general reader: at the time of this book's publication, Baltimore-bashing was practically a national sport among scientists. Kevles set out to write a balanced account, and he has done so-- it is a good job all around, as Yale recognized when it gave him an endowed chair recently (Caltech's loss, alas!). Information subsequent to its publication only enhances Baltimore's stature. Unfortunately, like the French Dreyfus case that it resembled at times, too many prominent people said too many harsh things about Baltimore that they cannot retract. Contrary to at least one of the editorial reviewers, it is clear now that Kevles was too hard on Baltimore and company, but so many people attacked Baltimore(Nature's Maddox, Paul Doty, Jim Watson, W.Gilbert, J Darnell, G. Blobel, and a whole nascent federal bureaucracy, inter alia) that these contemporary anti-Dreyfusards will never be refuted. Be that as it may, read this account to get a detailed study of how scientists and government can go wrong, all while trying to do the right thing.

Important and revealing but overlong

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

"The Baltimore Case" tells a fascinating, frightening story well, but in far too many pages. The previous reviewer describes the details of the case, which are familiar to most biologists but still misunderstood by many in the sciences as well as by the general public. Mr. Kevles is a descriptive master. He lays out the facts of the case in as objective a manner as I think is possible and he makes the murkiest of quarrels clear (although more figures would have been useful), but his book is very repetitive, is excessively detailed, and by the final chapters a feeling of déjà vu permeates every page. That said, he provides a very important service by convincingly showing that the Baltimore case was primarily a congressional and media fiasco perpetrated under the guise of scientific justice. Some might say that scientists are placed on a pedestal by the non-scientific public and that it is a good thing for scientists to be monitored by "impartial" parties to "keep them honest". Maybe so, but in a country whose populace still fights the teaching of evolutionary biology in public schools and rejects genetically-modified foods without a basic understanding of biology, whose congressional members only support applied research that is fodder for votes, and whose media have trouble reporting the most basic scientific discoveries accurately or without sensationalizing them, the policing of scientists should be done very carefully, and "The Baltimore Case" shows why. When ignorant and incompetent individuals like Feder and Stewart are allowed to impact science for transparently self-serving reasons, and powerful politicians like Dingell are given free reign to try, convict and punish dedicated individuals with ill-concealed intellectual jealousy, the entire scientific enterprise in the United States is placed in serious jeopardy. The scientific community, like any other, will turn defensive, in-fight, and self-destruct, and the public will view scientists with greater suspicion than ever. If, after Margot O'toole lodged her initial complaint, independent scientists had been allowed to validate the work under question, which was later shown to be unimpeachable, millions of dollars would have been saved and many years of anguish would have been avoided. Instead, intellectual laziness and administrative incompetence won out and a travesty ensued. Mr. Kevles should be congratulated for making this simple, refreshing fact clear.

A fascinating account of a historic scientific fraud case

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

The Baltimore case was really the Imanishi-Kari case. A young scientist in Theresa Imanishi-Kari's lab, Margot O'Toole, approached her superiors with a disagreeing opinion about one of the papers published by her superior and co-authored by Nobel Prize winner David Baltimore.Two committees found that there had been error, but not misconduct or fraud. Somehow, the case was brought to the attention of two self-appointed "fraud-busters" at the N.I.H., and a full-scale investigation was launched. The secret service was brought in to examine the lab notebooks and a draft report finding evidence of fraud was leaked to the press. A public controversy ensued, especially when it became clear that Imanishi-Kari did not have access to her own notebooks to prepare her defense. The case dragged on for a decade but ended in a triumphant exoneration on all charges. The book pleased me for two reasons : 1) It made clear the scientific controversy, which had often been overlooked in the press reports of the time, and it also defined the difference between scientific disagreement about the interpretation of data,versus fraud or error. 2) The book described the frightening escalation of the charges against Imanishi-Kari. What started out as an inability to reproduce experimental results with a temperamental reagent, ended with accusations that a third of the experimental notebooks would have been falsified ! One moral lesson can be drawn for all scientists : make sure your notebooks are organized in perfect chronological order !