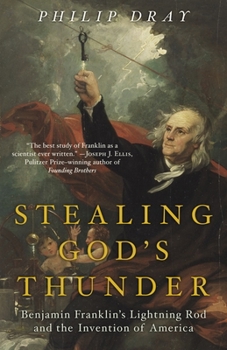

Stealing God's Thunder: Benjamin Franklin's Lightning Rod and the Invention of America

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Stealing God's Thunder is a concise, richly detailed biography of Benjamin Franklin, viewing him through the lens of his scientific inquiry and its ramifications for American democracy. Today we think... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0812968107

ISBN13:9780812968101

Release Date:December 2005

Publisher:Random House Group

Length:304 Pages

Weight:0.56 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.2" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Benjamin Franklin, the scientist

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Stealing God's Thunder by Philip Dray is extremely well-written. Unlike many biographies of Franklin, it focuses on his science first and his role as a founding father second. This way of characterizing Franklin's life was more interesting than writing about him as a politician first and scientist second. What is most interesting is the influence that Franklin's science had on his politics and on his philosophy. Dray wrote about complex subjects without ever becoming too wordy and overall the book was extremely readable. Some of Franklin's most interesting work was put into small inventions rather than large ideas. Franklin said that the armonica, a device that spun glass to make music, was his favorite invention. Although Franklin did important work linking lightning and electricity, and as a proponent of lightning rods, his small inventions were extremely interesting as well. Franklin learned a great deal about electricity during his life and this allowed the next generation of scientists to build on his discoveries. He also challenged the views of Christianity, while still believing in God and remaining religious throughout his life. Franklin believed in the power of reason and he thought that this did not conflict with belief in God. Franklin is one of the most interesting characters of the American Revolution and the Enlightenment.

A Patent Lawyer Speaks

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I am a registered patent agent and a retired patent attorney, so this review is slanted from the view of the patent professional. "Stealing God's Thunder" details the history of Benjamin Franklin's invention of the lightning rod, and goes on to sketch Ben's role in the invention of the United States' system of government. In a few places, the book touches on subjects which are of particular interest to the intellectual property professional. Eschewing a patent, Franklin published a complete description of his lightning rod invention in "Poor Richard's Almanac" in November 1753. Much to our delight, the author includes the entire text of the article in his book, on page 91. The Poor Richard article is entitled, "How to Secure Houses, etc., from Lightning." Further, in his "Epilogue," the author makes the following statement: "Benjamin Franklin's refusal to patent his `instrument so new' likely contributed to the competitive free-for-all that began to characterize lightening rod design, manufacture, and sales within a few decades of his death." This is so wrong on so many levels I hardly know where to begin. Dray seems to say that because Franklin did not obtain a patent on his invention, the market forces did not apply to Franklin's invention. Why is this the case? Also, why "a few decades" when a patent's term was generally limited at the time to 14 years. You will see evidence of this later on in the review. And what does his death have do with it when the rod was published in 1753 and Franklin lived until 1790? However, Dray does not confine himself to the lightning rod. He also discusses the invention of the famous "Franklin stove," inter alia. In discussing the stove the author describes Franklin's philosophy toward patents: "As he would with all his inventions, Franklin, although he stood to profit from the sales of the stove, did not apply for a patent. He believed that products of the human imagination belonged to no one person, and should be shared by all." In this we are reminded of the comments of Rosalyn Yalow, a physicist who, together with Soloman A. Berson, a physician, developed radioimmunassay (RIA). On receiving the Nobel Prize, Yalow said, "In my day scientists did not always think of things as being patentable. We made a scientific discovery. Once it was published it was open to the world." Fortunately, today's scientists may take advantage of the Statutory Invention Registration (SIR). For further details, see, "Rosalyn Yalow's Patent and H.R. 1127" in "The Law Works," January, 1996, at page 17. One further aspect of the book may be of particular interest to the intellectual property community, and that is the aspect of the patents of the colonies and the States. Remember, Franklin's rod was published in 1753 and the United States Constitution was not ratified until 1789 and the first federal patent law was not enacted until 1790. As Dray notes about Franklin's refusal to patent his inventions, on page

Franklin the Scientist Enables Franklin the Founder

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Surely the most lovable of all the rebels who founded our nation was Benjamin Franklin. And indeed, most people think of him as a statesman and founding father who dabbled with some genius in other arenas as well, as a printer, inventor, chess player, satirist, autobiographer, and scientist. It is, however, as scientist he got his initial fame, for his investigations of electricity and his invention of the lightning rod. In _Stealing God's Thunder: Benjamin Franklin's Lightning Rod and the Invention of America_ (Random House), Philip Dray has drawn attention specifically to Franklin the scientist. We hardly think about using electricity every day, except if the power is somehow cut, and no one thinks too much about lightning rods any more, and everyone can see that lightning is a big electrical spark, so why make a fuss about Franklin's risky experiment of flying a kite in a storm that proved it so? What is important, what made Franklin an international celebrity, is that no one else in his time had much of an idea about what electricity was, and he gave us the terms and means with which we could continue an investigation of a primal and useful force, as well as keep it from harming us. Franklin's scientific reasoning resulted in the fame that allowed him to bring such reasoning to the cause of liberty. Having turned over his lucrative publishing business to agents who would work for him, Franklin had time to tinker with wires and Leyden jars that could store electricity. He enjoyed making demonstrations of his experiments to his friends; he was always one for attempts to improve others. For most of his researches, Franklin was doing pure science. This would not bother most scientists today, but Franklin wanted electricity not only to be understood, but to be useful; he was only partially successful in this, but he was hugely successful in his invention of the lightning rod, which was a product of his electrical experimentation. He must have been dismayed that there were religious objections to his invention. Franklin certainly did not believe that any god sent thunderbolts down to destroy and instruct us, but many divines did. Lightning had the interesting quality of seeming directed; a lightning bolt might take out one particular sinner, whereupon all remaining could speculate why God had chosen that one rather than others for such a spectacular display of divine displeasure. In 1755 when a powerful earthquake struck New England, clergymen argued that God was taking revenge for having his power of lightning stolen from him. It was not the first time or the last that the church would show its resentment over the encroachments of science. It was Franklin's scientific work that ingratiated him to the Frenchmen he had to win over to the American cause and made his tour there such a success. It was a Frenchman who captured Franklin's legacy in the motto: "He snatched lightning from the sky and the scepter from tyrants." Franklin m

Franklin the scientist.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Most biographies of Benjamin Franklin tend to focus on his role as statesman as opposed to his role as scientist. Given the impact he had on the raod to independence and nationhood for the U.S. this is entirely understandable. However, he was in his time revered as much for his impact on the world of science as he was for his role as a statesman. In Stealing God's Thunder : Benjamin Franklin's Lightning Rod and the Invention of America Philip Dray attempts to reverse this bias and portray Franklin's life with the focus on his role as a scientist in the forefront. What is most interesting in this approach is how much one sees that there is nothing new under the sun when it comes to the human condition. The emotional debates over evolution, genetic engineering, cloning and so on have their predecessors in the advancements of previous times. Dray focuses on Franklin's invention of the lightening rod, what today seems the most benign of devices, but which stirred many deep emotions and much religious opposition in its time. By inventing the lightening rod there were those-and they were many-who accused Franklin of "playing God". (Does that sound familiar?) They believed that Franklin, by directing lightening into the ground was adversely affecting divine balances between the heavens and the earth. He was roundly condemned in his time for doing so by many very prominent clergy, including the pastor of Boston's influential South Church, Thomas Prince. The attacks had their effects. Franklins image was tarnished among many fundamentalist Christians and the use of the lightening rod declined considerably after these attacks. Yet it overcame these attacks. In what can only be described as a perverse turn, the efficacy of the lightening rod was demonstrated in Europe. The invention of large scale field artillery required that huge quantities of gun powder be stored. Often, it was stored in the vaults of churches. When lightening struck, the results could be devastating. The end result was European governments adopted widespread use of the lightening rod to save churches utilized to protect the means of war. This is an excellent book that not only provides a unique perspective on Franklins life and legacy but also, in the process, puts the public debates of our own age in a very interesting light as well.

When Reason Energized a Nation

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

From The Washington Post book review, [...] Reviewed by H.W. Brands Sunday, August 7, 2005; BW03 The concept of degeneration in American political history is so broadly accepted as to be almost unchallengeable. In the days of the Founding, giants walked the earth; Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, Madison and the others seized independence from Britain and placed the new nation on its republican path. Since then it's all been downhill; no subsequent generation, and certainly not ours, could have accomplished what those demigods wrought. This conclusion is correct, but the cause typically adduced is wrong. What separates us from the Founders is not a talent gap but a temperament gap; what we lack is not intellectual power but collective confidence. Philip Dray's succinct recounting of the role of science in Franklin's life and thought affords a useful reminder of how thoroughly America's republican experiment was a product of the mindset of the Enlightenment: a belief that all things are possible to self-confident human reason. Dray, the author of the prize-winning At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America, points out that while later generations looked on Franklin as a statesman and diplomat who dabbled in science, his own generation deemed him a scientist who moonlighted in politics. Dray covers all the high points of Franklin's scientific career: his apprenticeship as a journalist during a violent debate over inoculation for smallpox (literally violent: Cotton Mather escaped death when a homemade bomb tossed by an opponent in the debate failed to explode); his observations of the Gulf Stream and other marine and atmospheric currents (which finally convinced stubborn British sea captains to heed the advice American whalers had been giving them for decades); his prescient studies of demography (which forecast with uncanny accuracy the growth of the American population); and, of course, his investigations into electricity (which won him world fame and might have brought him a fortune had he not eschewed a patent on the lightning rod). Dray relates these parts of the Franklin story with energy and economy. His treatment of the electrical investigations, especially of the development of the lightning rod, is the fullest currently available. Other authors have noted the skepticism that naturally greeted the concept of the lightning rod -- who of sound mind would want to crown his house with something that seemed to attract lightning? -- but none has pursued the battle over lightning rod design -- one point or several? sharp or blunt? -- with such thoroughness. Dray devotes less attention to the subject of the second half of his subtitle: the "invention of America." He walks Franklin through the seminal political events of the Revolutionary era -- the Declaration of Independence, which Franklin helped draft; the Revolutionary War, which Franklin helped win by his diplomacy in France; the Constitutional Convention of 1787, wh