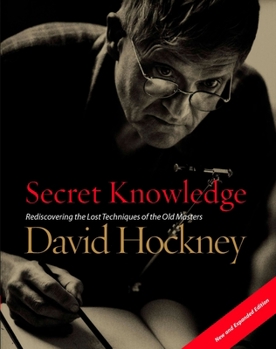

Secret Knowledge (New and Expanded Edition): Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Join one of the most influential artists of our time as he investigates the painting techniques of the Old Masters. Hockney's extensive research led him to conclude that artists such as Caravaggio, Vel zquez, da Vinci, and other hyperrealists actually used optics and lenses to create their masterpieces. In this passionate yet pithy book, Hockney takes readers on a journey of discovery as he builds a case that mirrors and lenses were used by the great masters to create their highly detailed and realistic paintings and drawings. Hundreds of the best-known and best-loved paintings are reproduced alongside his straightforward analysis. Hockney also includes his own photographs and drawings to illustrate techniques used to capture such accurate likenesses. Extracts from historical and modern documents and correspondence with experts from around the world further illuminate this thought-provoking book that will forever change how the world looks at art. Secret Knowledge will open your eyes to how we perceive the world and how we choose to represent it.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0142005126

ISBN13:9780142005125

Release Date:October 2006

Publisher:Avery Publishing Group

Length:336 Pages

Weight:4.15 lbs.

Dimensions:1.0" x 9.4" x 11.8"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Hockney's Evidence is Thought-Provoking, Verifiable/Falsifiable

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Critics and reviewers who have rated Hockney's Secret Knowledge low seem to me to overlooks some major points. Some of these I find more persuasive than the the issue of alleged perspective misjudgment which seem to attract the greatest heat. 1. H points out that a huge majority of portraits in the period show the model as left handed--some 80%. This is consistent with use of lenses and inconsistent with the frequency of left-handedness in the population. Now, here is a verifiable fact. Are H's numbers right--or are they not? 2. H is not claiming that everyone 1400-1650 was a poor draftsman. At least in what I've seen so far, he doesn't claim e.g. that Rembrandt used optics. Part of his evidence is however that some artists who were great painters were not great draftsmen--their painting exceeds in accuracy their draftsmanship. Now this appears to me again something that is verifiable by a third party. (The question of H's own draftsmanship abilities is totally irrlevant. I don't like his art much myself). 3. In a highly competitive art market, where realism counted, what is the likelihood that artists would >not< use devices that helped them both with accuracy and speed? Even if the great Ren artists could paint and draw realistically without optics (and their education certainly was thorough), throughput and competitive concerns surely would have pushed them in that direction. <br /> <br />4. To my knowledge, no one has responded to H's claim that the change in light to very strong with dark shadows from about 1400 (light is flat) to 1500 is very consistent with use of optics. Yes, that is not the only possible explanation. But from a philosophy of science perspective, this phenomenon and the phenomenon of increased accuracy need to be explained. H at least offers an explanation. The burden of an alternative explanation is on the critics. H's hypothesis could be falsified by showing that in fact strong lighting was used before this period and flat lighting afterwards. <br /> <br />5. Another phenomenon for which H has an explanation but for which I haven't seen alternatives is the fact that in many realistic paintings, depth of field is evident. An example is the famous Vermeer milk pitcher painting. H has an explanation of why the foreground breadbasket is out of focus, while the background basket is (oddly) in focus. If a critic doesn't like H's explanation, he/she should provide an alternative. <br /> <br />6. H shows that in some cases extremely precise scaling is evident--scaling that would be very difficult to do by hand. Prof Falco, the optics and superconducting physicist who collaborated with H., has done the math and claimed that obtaining such accuracy by hand is very difficult since the error is (as I remember) under 2%). Doing anything by hand with under 2% error is quite a feat--including reconciling bank statements :)-- never mind drawing. Here is another phenomenon in which either the factual statements by H and Falco can be

Fascinating historical reconstruction.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

The premise is simple: Hockney believes that the Old Masters of European art used tools and techniques of which little record remains. This book presents his justification for that belief. The first half of this book is visual. It shows the original paintings and drawings that led Hockney to this idea. Once it's pointed out, many signs are unmistakable: odd proportions in otherwise masterful works, inconsistent perspective drawn by people who really knew perspective, and a few other better-known oddities. Although I'm not a fan of Hockney's own work, I respect the training and sensitivity that picked out these features. Hockney goes on to show how these artifacts could have come from use of a family of optical tools, including camera lucida and several variants on the camera obscura. This is where he brings the most to this book, in trying the tools himself, as an artist, and seeing what unique features each tool imposes on the resulting artworks. This is what has so many critics upset - the idea that the Old Masters might have used every tool possible to complete their commissions faster, and to give their patrons the most pleasing result for the ducat. Those critics know about the assembly-line work in some of the Old Masters' studios and who know about the other mechanical aids that are well documented, but squawk at the idea of adding another tool to their toolboxes. Huh? Hockney's evidence is often circumstantial, since painting was (and often is) a secretive and competitive business. Still, he offers a good story, and the second half of the book adds a strong foundation of written records to the structure. This is the book's weakness, though. Hockney is an artist, not a historian or optical technologist. He chose a story-telling format for presenting his findings, the letters he exchanged with scholars and specialists in other fields. It has a friendly look, but lacks in density and in organization of the historical records. Despite its many flaws, I find it a fascinating study. Hockney really brings history to life, with his own hands, dispelling the idea that historical study is a dry, dusty practice. His documentation lacks in formal rigor, and he addresses the Great Masters about whom people have strong sentiment. Some people see that as iconoclasm for its own sake - guys, get over it. -- Address his facts with facts. Name-calling says more about you than him. -- Picking one nit (and there are lots) doesn't pick apart the whole presentation. -- Don't assume that Hockney's own art (of which I'm not a fan) decides the merit of his historical analysis. -- Accept the idea that his eye may be better than the words he can put to his vision. It's an honest and vivid account, with a good base in reason and fact. It deserves respect on that account, and works hard to earn the reader's enjoyment. I recommend this to anyone interest in the history and practice of visual art. //wiredweird

A "mark maker's" Gratitude

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

The book came this morning. I opened it here and there for an hour or so. It is refreshing to see these issues addressed by a real mechanic/maker rather than Art Historians who in the end are audience, (well? educated audience) David Hockney has moved lots of paint and much else; he knows about these things, these pictures. I feel like I was talking shop with another painter this morning. What a book! and what a clear and direct use of digital technology to make a book. The book is revelatory because Hockney always reveals, so matter of fact, a man explaining his trade, saying it as it is.Can we doubt the influence of optics on pictures? Heck no! Hockney easily proves that. It's all the other stuff he does along the way; Hockney has a good time when he works, he shares his good time with us. The luckiest readers of this book will be the non-painters. Hockney is going to tell them how it is to think like a painter. For me, it's so cool to look at (discuss? ) pictures with Hockney. I'm going to take this book in pieces, savor my time with it2/4/02 Optics and painting/drawing both make edited copies of reality; these flat things we call pictures. Did the painters trace, draw, collage or all three; does the camera? It's all mark making. We make pictures so why would we not look at other pictures. A tree can't tell you how to draw it but a drawing of a tree just might. Huge numbers of people are still seduced by optical looking paintings; it is something of a standard. In economics that's called demand and over the centuries painters have fulfilled that demand. We still like all those pictures. Hockney is still right, optical pictures were and are the overwhelming force in the set of all pictures. Watch TV for an hour and you see vastly more frames than anyone in the 15-19th century saw in a life time. Hockney simply pointed at an evergrowing forest of optical images; As usual. the scientific and historical types miss the forest because of the trees; for painters the big picture is the picture. All the detail in the world won't help a ridiculously constructed picture. The problem is the historical and scientific people are academics, painters are people who make things; it is a different form of intelligence. Clearly academic skill is prized in this culture but there are many other kinds of knowing; the academics should learn to see them. As for the man who encouraged his son to trace; right on guy. If the kid wants to be a painter all that use of a pencil; that feel of how flat things work, even thinking about the picture, will be useful. Just remember to also encourage the making of more freehand marks; way more. Drawing from nature is it's own game; one that shouldn't be missed and drawing from imagination is cool too. In the end it all comes together.

Beautiful and enlightening

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This is meticulously and beautiful book, that supplements the photos of art with excellent detail closeups. David Hockney writes in an accessible and lively style. Non Artists will have no trouble following his argument, though we may not be able to fully judge it as well as art experts can.But that's not the only accomplishment of this book. Following the path of Hockney's investigation, we learn an enormous amount about painting and how it is accomplished, not just in the past but how it ties to today's techniques. As a still and movie cameraman I found it very illuminating and even useful.

Wow!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Great book. Reads like the denouement of spell-binding mystery novel with the visual and textual evidence mounting piece by piece until the conclusion seems inevitable. As a working artist, Hockney teases out clues that may have eluded art historians. The book itself is a piece of artwork with excellent reproductions, skillful layout and beautiful typography.There is one sore spot. Historical and scientific types will quickly notice that Hockney reached his conclusions BEFORE his two year search for evidence and that weaknesses in the argument and evidence are not fully considered. The examples appear selective and are possibly not representative. Looking at the sample artwork, you can see his point but would not be suprised to hear valid alternative explanations. Though not proof positive, the work is persuasive, enlightening and more than a little revolutionary.