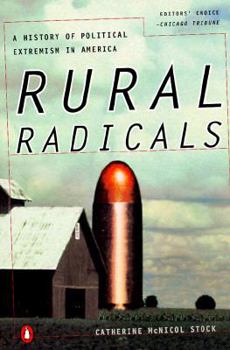

Rural Radicals: Righteous Rage in the American Grain

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

When terrorists blew up the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, a shocked nation could scarcely imagine the perpetrators were home-grown. If they were, Catherine McNicol Stock... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0140268472

ISBN13:9780140268478

Release Date:December 1997

Publisher:Penguin Group

Length:240 Pages

Weight:0.40 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.1" x 7.9"

Age Range:9 years and up

Grade Range:Grade 4 and higher

Customer Reviews

3 ratings

Angry and Disaffected

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Catherine Mcnicol Stock's treatise on agrarian radicalism is not exactly the book I thought I was buying, but I discovered that it is an excellent addition to rural history as well as the history of radicalism in America. This book was written in response to the shocking revelations in the wake of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, an attempt to place rural, white male radicalism in context. Her thesis states that this radicalism and violence is not new, going back as far as 1676. She reconciles seemingly paradoxical elements: rural producers, right-wing, left-wing, and vigilantes. This may seem contradictory, but it shouldn't in light of a long history of anti-government protest and intractable problems running counter to the dominant American culture. One interesting and disturbing example Stock provides is that of Jim Jenkins of Minnesota. He killed the banker who had foreclosed on him in the desperate agricultural times of the early 1980s. The rights of farmers have been sacrosanct in this country, but unseen economic and political forces have driven some to desperation. I agree with "One Man's View" that many producer radicals, like the Populists, were not vigilantes. I, too am a student of Populism, and I assert that many were inclusive, egalitarian for their time, indeed "virtuous." However, Stock's thesis is still valid; it is conceivable in radical ideology to be both a producer and a vigilante. I recommend this work, but it must be carefully read as not to be misinterpreted. This ground has been trod by academia before, but I don't remember this particular thesis. I am sure that this filled a need at the time of its publication; explaining murderous rage does not excuse it. Anyone can still learn from this impressive scholarship. It isn't so timely now, but it isn't antiquated. The emotional jolt from that time has ebbed, but as history has shown, this is an American tradition. Sometimes the politics of hope and the politics of hate are hard to differentiate.

Interesting contrast of producer radicalism and vigilantism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

The author contends that the media discovery in the 1990s of rural militia and even the Oklahoma City bombing should not be too surprising because they follow in a long line of rural radicalism. She considers rural radicalism as a distinct phenomenon because of the nature of rural life itself. Rural residents, especially the common folk, often endure difficult and even harsh lives. Urbanization, modernization, consumerism, and the rise of huge business interests and bureaucratic government have impacted or have been felt to unduly impact rural residents. Rural people have generally turned inward toward their local communities for support in the face of difficulties. But at different periods in our history these small communities have erupted, often extra-legally, to contend with these various hated forces.The author distinguishes between producer radicalism and vigilantism. The former category is much concerned with economic issues from unfair land laws and practices, distant and unresponsive legislatures, burdensome taxation, judicial favoring of creditors, and monopolistic businesses, especially railroads. The Populists of the late 1800s are the prime example of producer radicals. Vigilantism shares some of these same concerns, but is slanted towards external forces or people who are seen to be a threat to a closed way of life. In some cases, as in pre-revolutionary North Carolina, vigilantes have operated against criminal elements in the absence of effective law enforcement but have been far more likely to identify and inflict harm on scapegoats along racial, ethnic, religious, and political lines. The KKK is perhaps the foremost example of a vigilante group.The author trys to convince that producer radicalism and vigilantism are two sides of the same coin. This reviewer does not find that the case is made. The Populists had legitimate complaints and found responsible ways of expressing them. They did not hate the federal government, even advocating for the nationalization of some industries. Some of their platform was adopted during the Progressive Era. Vigilantes in lieu of operating from any careful analysis of their situation seem to cling to wild conspiracy theories usually involving the federal government and then proceed to select vulnerable victims to assuage their frustrations. These are not the virtuous citizens of producer radicalism.The book is a very good survey of the various rural radical groups through our nation's history. While I do not agree with a central tenet of the book, maybe others would. In any event the book is quite worthwhile.

It's history with the hair and hide left on it.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 26 years ago

This book reads as easy as fiction. It's an excellent study for anyone who wants to add a mega dose of reality to what they didn't learn in school. And it adds keen perspective to today's and tomorrow's news stories about radicalism in the United States. It's a must for the serious reader's bookshelf.