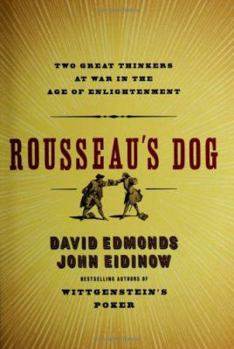

Rousseau's Dog: Two Great Thinkers at War in the Age of Enlightenment

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 1766 philosopher, novelist, composer, and political provocateur Jean-Jacques Rousseau was a fugitive, decried by his enemies as a dangerous madman. Meanwhile David Hume--now recognized as the... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0060744901

ISBN13:9780060744908

Release Date:March 2006

Publisher:Ecco Press

Length:352 Pages

Weight:0.40 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 6.1" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

CONSTANT CONJUNCTION

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Is there in all the world a sillier spectacle than that of two intellectuals in a public dogfight? Any reader of academic journals must be familiar with that kind of thing, but the topic of this book features not just any old intellectuals but two of the most influential in 18th century Europe. J-J Rousseau was the harbinger of just about every major intellectual trend that has occurred since, from romanticism to the environmental movement. He invented autobiography, and his communicative talent was such that he was feared and hated for his nonconformity by various civic bodies, notably in Geneva. David Hume was not one to rock civic boats, but his Treatise of Human Nature is a landmark of analytical logic as influential, and indeed overpowering, in its own field of thought as Newton's Principia was in its. Hume and Rousseau experienced each other's company for no longer than 4 months, as this book usefully reminds us. I could not help but recall Hume's famous argument in the Treatise that we can only ascribe any kind of continuity coherence or consistency in the matter of cause and effect through `constant conjunction' - e.g. if we expect the sun to rise and set in a certain manner it is only because every time we looked previously that was the way the thing happened. When the fugitive Rousseau was first introduced to Hume, the latter was experiencing the greatest social success of his life, as an attaché at the embassy in Paris. Without waiting for constant conjunction he grandiosely undertook to arrange asylum for Rousseau in England, but 4 months of personal acquaintance taught him that he would have been better following his own reasoning in the Treatise and gaining a clearer idea, from more constancy in the conjunction, of what to expect from his protégé. I found this book absolutely riveting, but any reviewer needs to declare an interest - whose side is one on? I am on Hume's, so it is up to me to make allowances for that just as it is up to the authors, although they do their best to seem impartial. Bertrand Russell summed the issue up cogently if a little too neatly when he said that Rousseau was mad but influential while Hume was sane but had no followers. To me, Rousseau was a monster of paranoia and self-concern, and Hume was more than slightly naïve when Rousseau reverted to type and publicly portrayed Hume's efforts at assistance as being some dastardly plot. However badly Hume may have mishandled the matter, and even if he let down his own standards of strict truthfulness at times, he should not have been treated by Rousseau as he was. I can understand entirely how he went doolally, but I must remind myself that I start with a prejudice - if I had lived at the time I would have wanted to know Hume, but I can't imagine any epoch of history in which I would not have wanted to avoid the likes of Rousseau. The authors are or were BBC journalists, and they make a very good fist of living up to the standards of impartiality that the

A Lap Dog of a Book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Using the same formula the authors had with "Wittgenstein's Poker", this book is an excellent popular work of intellectual history. Using a single incident for the jumping off point, it allows for an opening for a broad view of Enlightenment society and the state of philosophy in that era. Full of juicy gossip like a modern scandal sheet, the characters of David Hume and Jean-Jacque Rousseau are brought to life, often in their own words, to remind us that even the wisest of philosophers are still human.

Engaging and Intelligent

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I loved Wittgenstein's Poker, and I was not disappointed with Rousseau's Dog. David Edmonds and John Eidinow write in the same witty and intelligent style, leaving just enough unsaid to stimulate your own thought and understanding (this subtle art of understatement has been sorely lacking lately). Reading the book I could freely engage in the discussion and create my own opinions about the events, I felt respected by the authors, and I thank them for that. The book describes in great detail the infamous personal conflict between David Hume and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. As you can expect now from David Edmonds and John Eidinow, there is much more: not only the portraits of both protagonists are colorful and compelling, but the conflict itself serves as a central theme for a vivid account of the very interesting time in European history. The authors used letters and newspaper articles of the time to re-create an engaging picture of the cultural atmosphere in Europe in 1760's. One of the most intriguing discoveries for me was the fact that, on a human level, we may understand a lot more about XVIII century than about our time because in the past people regularly wrote letters discussing not only the events of the day, but their feelings. Unfortunately, we have lost the sense of importance of our lives (funny as it is, but Jean-Jacques, this great trivializer, may be the one to blame for it). Rousseau's Dog is well-edited and carefully published. At the end of the book you find Chronology of Main Events, Dramatis Personae (a paragraph-long description of about fifty main characters and historical figures mentioned in the text), Selected Bibliography, and Index. Rousseau's Dog is not for everyone, but if you are interested in history of ideas and amused by psychological investigations, this is a book for you.

A Marvelous Book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Edmunds and Eidinow delighted and educated us with WITGENSTEIN'S POKER and (the underappreciated, but equally-rewarding BOBBY FISCHER GOES TO WAR). ROUSSEAU'S DOG completes the hat trick. It is, quite simply, marvelous. A fascinatingly human story, well-told; at the same time, an engrossing and iluminating work of history. A must-read!

Dogged by paranoia

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

The authors have earned fame for a hugely successful earlier book, Wittgenstein's Poker, in which a poker played a symbolical part in the dispute between Wittgenstein and Popper. Rousseau's dog Sultan plays no such part in this book about the antagonism that developed between Rousseau and Hume. Only on the penultimate page is there a single paragraph in which the authors comment on the unconditional love between man and dog that was the yardstick by which Rousseau judged all other friendships and to which none of his other friendships could live up. But the title might also have another explanation: two or three times in the text the authors have invented another "dog". The philosopher Grimm had written about the "companion who will not suffer him [Rousseau] to rest in peace", meaning the paranoid personality which he thought was Rousseau's alter ego. Grimm does not describe this alter ego as a dog, but the authors see it as one, doubtlessly having in mind that Winston Churchill had called his own depression his Black Dog. When Rousseau was being driven from one place to another on the continent because of the authorities there objected to his writings, David Hume, then serving at the British Embassy in Paris, had invited Rousseau to seek asylum in England, had brought him over in 1766, and intended to help him there in any way he could. Unfortunately Rousseau was by that time a florid paranoiac. Both in France and in England woundingly satirical but anonymous writings were circulating about him, and Rousseau suspected that the kindly Hume had had a hand in them and was plotting with his enemies against him. He wrote some bitter letters of accusation to Hume, and also denounced him in letters to his contacts on the continent, some of whom were also friends of Hume's, and this forced Hume into publishing his own defence. The nature of the dispute between them was not of a philosophical kind at all (unlike, say, that of the dispute between Wittgenstein and Popper or that between Leibniz and Spinoza, so brilliantly examined by Matthew Stewart in his recent book The Courtier and the Heretic - see my review). Of course it could have been about philosophy: Rousseau was committed to the romantic and emotional approach, Hume to the ultra-rational examination of philosophical issues; Rousseau had come to hate the philosophes, Hume had greatly enjoyed their company while he was living in Paris. The dispute was not even overtly about their respective attitudes to society. Hume loved society and was at ease in it; Rousseau hated it and loved the solitary life. Such differences between them are handsomely set out in the excellent chapter 11, but if the two great thinkers were indeed "at war in the Age of Enlightenment" (the subtitle of the book), it is sadly not possible to dignify that war as one caused by differences in philosophy or life-style. Indeed, our authors do mention that in all the correspondence between Rousseau and Hume,