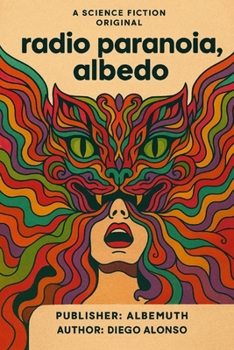

Radio Paranoia, Albedo

Prologue: Of the city, of the circle, of the letters

Every city, if it is true, predates its inhabitants and follows its ruin. Before the houses there was a trace; before the trace, a desire for order; before order, a tremor. This tremor - which the ancients called cosmos to contrast it with chaos - took the most parsimonious form of geometry: the circle. The doctors of the East said that the shore of the world was a ring of water; those of the West, that thought returns to its point; the copyists of the Middle Ages, that all writing, if it perseveres, ends up drawing its own prison. From these three conjectures this city is born: a perimeter that corrects itself, a center that moves, an alphabet that has turned to stone.

Surveyors will remember that no plane is innocent; theology, that no circle is. To draw a border is to suppose an inside and an outside; to inscribe a center, to choose a god. The superstition of architects, no less noble than that of poets, has repeatedly said that the perfect radius exists only at the cost of life; the circle, to be fulfilled, demands stillness. (The maps of antiquity, which feigned humility with their sea monsters, knew more than treatises; the orbis terrarum was less the image of the world than the pedagogy of its limits.)

The alphabet is no less guilty. It is narrated - in an apocryphal gloss to a grammarian of Alexandria - that letters were not invented to speak, but to measure. The city is supported by these invisible rods: the alif that straightens a street; the lamed that summons a portico; the MIM that curves a courtyard toward shade. These letters, repeated to the point of fervor, engender custom, and custom, government. They were once called archons to honor the equivocation: they command and are, at the same time, commanded by the form they dictate. It is not necessary to attribute a face to them. The seal and the correction are enough.