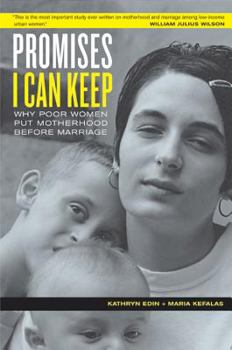

Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Millie Acevedo bore her first child before the age of 16 and dropped out of high school to care for her newborn. Now 27, she is the unmarried mother of three and is raising her kids in one of... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0520241134

ISBN13:9780520241138

Release Date:March 2005

Publisher:University of California Press

Length:316 Pages

Weight:1.35 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.3" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Why do we have a 40% illegitimacy rate?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

There has never been a country in world history with an illegitimacy rate this high. Yet it new seems standard for all western democracies. Why? And should we do anything about it, and if so, what? Edin and Kefalas spent many years researching this excellent book. And the results are enough to make you weep. They place the greatest emphasis for the decline in marriage on "the profound cultural changes America has undergone over the last thirty years" (p 200). Illegitimacy is now the definition of the new lower class. Yes, there are some university professors and the like, who, at the age of 35, finally decide to have a child. But most of the illegitimate children today come from poor mothers. Mothers with only high school educations. Mothers who frequently already have problems such as addiction, or mothers who came from single family households themselves. These single mothers will raise children who will have a 200% greater chance of ending up in prison than those parents, even those coming from the same economic backgrounds, who have the biological mother and father living with their own children. The result is a class of poor people that seems likely to become entrenched, unless we can do something to change the culture these women grow up in.

Why Put Motherhood Before Marriage?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Often when the question is posed as to why do poor women continue to have children before they are obviously -at least to the majority of Americans it is obvious-in the most opportune position to accomplish the task of parenting successfully, several common responses are usually offered. The most common retort may be that poor women don't have access to low-cost or free contraception and/or abortion providers, followed by claims that these women are just irresponsible and possess low ( or completely lack) moral values. Nothing could be further from the truth. Yes, poor women have less access to inexpensive contraceptive supplies and behavior that may be common in the ghettoes of America can be starkly contrasted against what is deemed acceptable in middle and upper-class communities. Yet it turns out that these differences have surprisingly little to do with why poor women consistently put motherhood before marriage. Sociologists Edin and Kefalas spent 5 years interviewing, studying and interacting with a group consisting of one-hundred and sixty-two women from eight impoverished communities to find the real answer to this perturbing question. Along the way Edin and Kefalas dispell the myths and stereotypes pertaining to poor men and women and their attitudes regarding motherhood and marriage. It turns out that rather than viewing marriage as an inconsequential and outdated institution, the interviewies revered marriage. What the authors discovered was that the women held marriage to such a high-standard and erected so many hurdles to be jumped before they would consider getting married that they effectively placed the hallowed institution outside of their reach in the near future. While the middle and upper-class follow the line of thinking that says "first comes love, then comes marriage, then comes the baby in the baby carriage", poor women women more often than not say "first comes infatuation, then comes the baby, then you move in together and plan for the wedding to take place in 5 or 6 years once the two of you are satisfied that you really know each other". Many of the things that these single-mothers say and do appear inexplicably contradictory, and at times, almost absurd. Yet to the women it all makes perfect sense. This book has numerous examples of "you have to read it to believe it" moments: for instance, there are the single mothers of two or three children who say that they don't want to get married just yet because marriage is such "hard work," as if raising several children in the heart of the ghetto while seemingly mired in abject poverty is a far easier task. The differences between the attitudes and behavior of poor and upper-class women is as stark as night and day when it comes to marriage and motherhood. Anyone genuinely interested in exploring these differences and crafting real responses to teen pregnancy and the high rates of out-of-wedlock childbearing in ostensibly dire circumstances should begin their exploration

The REASON woman have children they can't afford.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Not because they don't have access to birth control. These girls have children because it gives meaning to what they perceive as their otherwise meaningless lives. They need to be taught about self worth and self esteem at school that they don't receive at home. Then taught not what live will be like for them, but for the child they are bringing into the world for the own selfish needs. Until and unless this is done the cycle of poverty will continue to worsen no matter what the politicians do.

Keep this book to get real answers about youth pregnancy in the inner cities

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

The qualitative research in this book explains why so many young women in inner city communities are getting pregnant--and at increasingly younger ages than previous generations of their peers. 1996's welfare reform was driven by the specter of 'lazy' and unmarried teens having litters of children, but this book asks us to consider what responsibility means in neighborhoods with fading and non-existent infrastructure (p. 32). In these communities having children provides a form of tangible belonging. The kids are not the means to a monthly check, but a way to show the world that 'I had this many strikes against me and I became an adult'. Coming from a middle class background myself, I was particularly struck that these young men are telling women that they want to have a baby with HER eyes (p. 31) because I then realized that a baby would in fact be a representation of the two people having been together at one point. Ideally they would continue to stay together and raise the kid, but the authors (who previously wrote on urban poverty and welfare issues) also harbor no illusions about the young men who leave during a pregnancy and after a baby is born. Yet they also avoid finger-pointing and moralizing in favor of then examining the role which American society plays in encouraging these young teens to have sex and babies. Again we go back to the community infrastructure arguments and a disturbing but cognizant picture of complicity develops. Public figures restricting both reproductive and social services in these communities are ironically doing more to encourage subsequent generations to keep having sex. When the women become pregnant, the public figures (like some of the men in this book) develop selective amnesia and refuse to support policies which would help these kids ...etc. This book is an excellent read for students of welfare/welfare reform. It is also highly recommended for politicians because this group of pre-teens/teenagers is so maligned in American public policy (from abortion access to welfare). Finally, this book is an informative but exciting read for the average person needing to find out what goes on beyond their own little back yard.

On Target

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

A few moths ago I was in court as an attorney representing a teen-aged client mother losing her infant daughter to the foster care (DCFS) system because of parental neglect. While in court, the client excitedly announced to the judge that she was expecting her second child. She brimmed with pride. The judge dryly replied, "Oh." After court, my client cried because the judge didn't share her enthusiasm for her new bundle of joy. At another court appearance I represented one of five fathers who impregnated a single mother losing her nine children to the foster care system. The fathers were "high-fiving" each other and carrying on while waiting for the judge. Like the judges, I just didn't get it. I didn't understand what was going on. Did I miss something? Why? I guess we couldn't bridge the cultural gap between the urban poor biological parents (White and Black) and the middleclass. Edin is an excellent cultural broker and explains some of the striking cultural attitudes and differences between poor urban unmarried parents and middleclass. She gets into the thought process of a teenaged impoverished mother. She takes us into the world of the teenaged father---in many cases an older father. Edin elicits the cooperation of a difficult and closed population. Many of these parents are pushed around by society and the system, and are not trusting. A Social Worker might get a facil response: "Because she's my baby." As an attorney and advocate I can't ask some of the "Why's." Edin did and was able to get deeply insightful answers. Overall, a darn good book---one that you just can't put down.