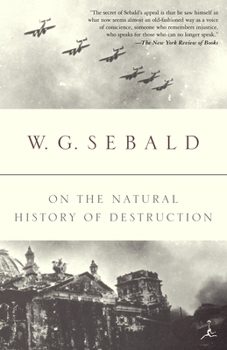

On the Natural History of Destruction

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

During World War Two, 131 German cities and towns were targeted by Allied bombs, a good number almost entirely flattened. Six hundred thousand German civilians died--a figure twice that of all... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0375756574

ISBN13:9780375756573

Release Date:February 2004

Publisher:Modern Library

Length:224 Pages

Weight:0.45 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Flies of the Lord

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Why was there so little German writing about the destruction of the war? And why was the little that did get done so steeped in mystic rambling instead of acute description and analysis? Sebald's theory: this was so for the same reason that enabled the Germans to go for their amazing reconstruction: they were so numbed by the experience, that they had turned off any perception and just put one foot in front of the other. And for the same reason the alleged war aim of demoralizing the German population failed. They did not stop to think about it. Sebald also does a good lot of destructive criticism on writers of the first hours: Kassack, Nossack, Mendelsohn, also Arno Schmidt get demolished badly (which hurts me in the case of AS, the hermit of Bargfeld, but admittedly the text that Sebald demolishes is utter crap). Boell gets off lightly, his contemporary novel was not published until decades later, because publishers did not think the public was 'ready'. Good stuff was only produced and published in the 70s: especially Kluge and Fichte. A special attention is paid to the previously thought respectable Andersch. Devastating. In principle the message stands: the firestorms, the reign of rats and flies was not written about from the inside. The area bombing concept was developed when Britain had no other choice: in no other way could they get back into the fight. Why was it continued when it was not needed any more and did more damage than good to the war effort? Plausible answer: two reasons: first, the material was produced and needed to be used, simple economic consideration; second, the propaganda effect on the domestic front was overwhelming. Never mind it was useless.

Not only the Germans have gaps in their consciousness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This is one of the most remarkable books written around World War 2. Whilst Sebald's primary subject is the lacunae and evasions in German texts around the experience of the Allied bombing campaigns of World War 2, the main essay of this collection also raises profound questions for any reader asssociated with the Allied nations of the war. The response in popular histories written from an Allied perspective is revealed in the wake of the Natural History of Destruction to be less than adequate. Am I alone in feeling a degree of shame and repulsion as a citizen of nations who also violated human rights in such cases as Dresden and Hamburg? More honesty on our part is called for ... this book offers much food for thought especially around the human feelings at ground zero Questions about whether this book assists the neo-Nazi cause and also the extraordinary tone (with strong overtones of Nazism)of the many angry letters received by Sebald further indicates how inadequate is later generations' response to the profound moral challenge of World War 2 - espcially now we are in the midst of another war where the goodies and baddies are not quite so easy to tell apart as they are in late night movies 3 other essays examine esteemed 20th century German literary figures in the wake of the war - these figures are less known outside of a German speaking context (with the exception of Weiss' theatre piece Marat/Sade) and serve to introduce them to a new audience The prose is vivid and evocative - it is a tragedy that this writer was killed in a traffic accident at the height of his powers.

Elimination as Defensive Reflex

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This posthumous volume of Sebald's non-fiction writing is a major contribution to German literary criticism and politico-cultural analysis. Accompanying his reflections on the traumatic impact of the air war against German cities are essays studying the very diverse reactions of three `witnesses' of that time as reflected in their post-war literary works. In AIR WAR AND LITERATURE, originally presented as the Zurich Lectures, Sebald delves deeply into some very uncomfortable questions. The air war on 131 German cities killed some six hundred thousand civilians and destroyed more than the homes of seven and a half million people. Why have these events resulted mostly in public silence for decades? Why have so few literary works attempted to speak to the traumatic impact on the population? Most Germans seem to have tried to come to terms with the realities of the war years by suppressing their immediate pain and the longer-term suffering. Sebald has thoroughly researched a multitude of authors, both in fiction and non-fiction. Yet, he deems their explanations unsatisfactory. Heinrich Boell is cited as one of the early exceptions, yet publication of his book, The Silent Angel, was delayed by forty years. Sebald contemplates the different causes for this persistent silence. For example, basing himself on a range of contemporary sources, he confronts the reader with a detailed description of the Hamburg firestorm. As disturbing as his account is, Sebald's reflective style makes it readable. His objective reporting neither criticises the Allies' campaign nor does he apologise for German actions leading to the war. He wonders, though, whether the depth of the traumatic experiences of this and other air attacks may have left many people numb and dazed, unable to express their reactions for a long time. The account of a young mother wandering through the station confused and stunned is one of several examples. Her suitcase suddenly opens onto the platform revealing the charcoaled remains of her baby. Sebald's intent is not to shock but to explain the deep sense of loss that must have been felt by people like her. He further contends that at that time in the war, the growing acceptance of guilt for the Nazi's atrocities led in many civilians to an acknowledgment of justified punishment by the Allied forces. Last, not least, after the war many Germans experienced a `lifting of a heavy burden' that they felt they had lived under during the Nazi regime. Concentrating on building the new Germany focused their minds on a better future. The publication (in German) of his Lectures in 1997 resulted in a range of reactions from readers. He reflects their varied views and comments in a postscript, thereby adding a fascinating 1990's dimension to his "rough-and-ready collection of various observations, materials, and theses". The three authors who are the subject of the essays in this volume may be better known to students of German literature and culture. The

Memory and war

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I found Sebald's descriptions of the Allied firebombing to be moving. One reviewer faults Sebald for his inclusion of several pages on the destruction of the zoo, because the reviewer thinks the original description that Sebald uses gives comfort to neo-Nazis. Perhaps it does, but that doesn't make it invalid. And if you look at the totality of this work, it certainly does not in any way condone Germany's Nazi past.What Sebald is discussing is human memories of the bombings, and the repression of those memories. He isn't discussing the rights or wrongs of the bombings, which he mentions only briefly in what he calls a postscript. I don't think this should be used, as another reviewer has, to argue that he is minimizing German guilt. You could take the other point of view equally well: that he is minimizing Allied guilt by not discussing criticisms of the Allied bombing campaign. These issues are not germane to his narrowly-defined topic. In other words, the book is not a history of bombing, nor is it a discussion of the ethics of bombing civilians; rather, it is a description of what people remember about these events in later years.I found the second part of the book, a discussion of Alfred Andersch, to be equally interesting. Here is a man who, according to Sebald, used his novels to rewrite the story of his life, and he wrote it as he probably should have lived it, rather than as he did live it. And he did this without ever apologizing for (or even admitting) his less than heroic behavior in real life. The last two essays were less interesting to me than the rest of the work. They might be more useful to specialists in modern German literature. This brings me to what I consider a defect in this book. Surely the people about whom Sebald is writing are not household names in the U.S. I think that the translator or publisher should have included brief biographies of these individuals.And while we are on this subject, I think the translator could have added to Sebald's footnotes too. In the section on Andersch, we are told that he divorces his wife in 1943 because she is Jewish, thus leaving her and their daughter at the mercy of the Nazi regime. But, although we are told of the fate of Andersch's mother-in-law, we are never told what happens to his ex-wife & daughter.All in all, however, I think this work is well worth reading. It's not one that you will forget once you have finished reading it.

A Posthumous Encore

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

WG Sebald died far too soon. In the past few years this penultimately creative German writer graced us with four novels, or memoirs ("The Emigrants", "The Rings of Saturn", "Vertigo", and "Austerlitz") that created a hunger for more great writing from this gifted man. Shortly after his untimely death "After Nature" was published and proved to us that the novelist so many of us regarded as a 'poet' was indeed a gifted Poet. Now, with the relase of this collection of essays yet another aspect of WG Sebald is revealed - a critical philosopher unafraid to shed light on aspects of his German descent like few other writers have.In "Air War and Literature" Sebald describes what the Allied Forces invasion and devastation of a country so reviled for its Nazi activities was like to the many Germans who remained after Hitler's time was over. It is not easy reading, this, understanding that the goal of the non-German world was to annhilate the land which had bred such atrocities. Yet Sebald does not plead the case for the German cities and people who were burned to the ground by Allied bombings. He instead turns inward to scold the Germans for not writing about their own 'victimization', the lack of writers to speak out about accepting guilt yet leading a path out of the heinous past to a future of repair and hope. He examines the effect of destruction on the great minds of the day, trying to find an answer why creative people were so intimidated by the terror of silence. To read about WW II from the German vantage is an experience few other authors have encouraged so tersly.In the remaining three essays, Sebald the critic in turn lambasts the shallow glory-seeking work of Alfred Andersch (who considered himself a greater writer the Thomas Mann!) and the sensitive, soul-searching works of Jean Amery, both writers who have addressed the post-War Gaerman psyche. And finally he critiques both the paintings and the late writings of Peter Weiss in one of the most tender homages imaginable.Sebald was a brilliant writer and a sharp, demanding critic, and time will place him in a position too early to visualize, so recent is the sadness of his passing. This is book that should be read by all those who love his novels, but also by those who want to further explore the incredible madness that once upon a time grew in Germany.