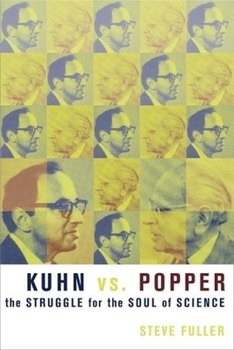

Kuhn vs. Popper: The Struggle for the Soul of Science

(Part of the Revolutions in Science Series)

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Thomas Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions has sold over a million copies in more than twenty languages and has remained one of the ten most cited academic works for the past half century. In contrast, Karl Popper's seminal book The Logic of Scientific Discovery has lapsed into relative obscurity. Although the two men debated the nature of science only once, the legacy of this encounter has dominated intellectual and public discussions on the topic ever since.

Almost universally recognized as the modern watershed in the philosophy of science, Kuhn's relativistic vision of shifting paradigms--which asserted that science was just another human activity, like art or philosophy, only more specialized--triumphed over Popper's more positivistic belief in science's revolutionary potential to falsify society's dogmas. But has this victory been beneficial for science? Steve Fuller argues that not only has Kuhn's dominance had an adverse impact on the field but both thinkers have been radically misinterpreted in the process. This debate raises a vital question: Can science remain an independent, progressive force in society, or is it destined to continue as the technical wing of the military-industrial complex? Drawing on original research--including the Kuhn archives at MIT--Fuller offers a clear account of "Kuhn vs. Popper" and what it will mean for the future of scientific inquiry.Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0231134282

ISBN13:9780231134286

Release Date:December 2004

Publisher:Columbia University Press

Length:160 Pages

Weight:0.74 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.7" x 8.6"

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Interesting but Confused

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Fuller's "Kuhn vs. Popper" tells of the authoritarian Kuhn and the libertarian Popper, and their separate ideals of science indicated below: (1) Thomas Kuhn, in The Structure of Science, related science to the fallibility of scientists, and this made science into a progression of phase changes (Kuhn's paradigm transitions). Science could not be separated from either scientist or from history. The ruling paradigm was an opiate, a habitual application of the one induction that gave its support to an authoritarian class; breaking the paradigm required something special. (2) Karl Popper's The Logic of Scientific Discovery departed significantly from Kuhn's view. Popper was a deductivist, and he wanted to bring scientific theories to the test of falsification, mere verification of the ever-go-lucky induction would not do. Popper's deduction was meant to eliminate induction by refutation, bringing science closer to an ideal that is independent of the fallibility of scientists. Popper wanted to liberate science from the dictates of the ruling paradigm. Fuller (page 31) writes: "While neither Kuhn nor Popper would care to deny that a specific paradigm may dominate the understanding of a particular slice of reality at a particular time, they differ over whether it should be treated as a source of stability (Kuhn) or a problem to be overcome (Popper)." Fuller's book in interesting (worth four stars) because of the contrast made between Kuhn and Popper found in the first half of the book. The confusion comes later, but Fuller (page viii) shows little affection for Kuhn from the get-go, and writes: "The more I have tired to make sense of Kuhn's words and deeds, the more I have come to regard him as an intellectual coward who benefitted from his elite institutional status in what remains the world's dominant society." Fuller tells us that Kuhn won the class struggle, and Fuller's own emotionality betrays his affection for Popper's libertarianism. From about chapter 13 on, Fuller stops comparing Kuhn and Popper directly, and Theodor Adorno and Martin Heidegger are noted. Fuller's views become more political as the reader approaches the end of the book. Politics can only be confusing. Despite Heidegger's Nazi past, despite the cold war and the Vietnam war, Fuller fails to discredit Kuhn's privileged professional life. Fuller's criticism of Kuhn's silence on moral issues goes nowhere, in my view. My impressions aside, Fuller has made a stronger case for his criticism in "Thomas Kuhn: A Philosophical History for Our Times." Nevertheless, there is no Popperian deduction that I know of that will remove the confusion from Fuller's politics. What Fuller is doing is not deduction, rather it is an exploration of history and it is dialectical. Fuller's dialectical path to truth is closer to Kuhn's history-knows-best-approach than it is to Popper's call-for-empirical-refutation, at least in my opinion. Yet if Popper's science was so wonderful in Fuller view why th

Fun read, but flawed

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Polemics are fun, and this one is no exception. Fuller is an excellent, energetic writer, and he seems to have read everything. If the result is more sizzle than steak, it's still a very interesting view of the divergence between two of the giants of 20th-century philosophy of science. Recommended. Karl Popper is about my favorite modern philosopher. His view of what science should be like, and the kind of liberating cultural role it should play, is inspiring. Thomas Kuhn, on the other hand, provided a very different, and much less exhilarating, picture of how science does, in fact, operate. In my experience, Kuhn's description is largely accurate, something Popper himself did not deny. If that is so, then this "debate" is between a normative theorist of how science should function (Popper) and an observer/analyst of how science does function (Kuhn). In a debate like that, the queston of "Who's right?" is not destined to lead much of anywhere. Fuller is critical of Kuhn for being a repesentative of, or even an apologist for, establishment "big science" that tends to operate beyond democratic political controls; Fuller's sympathies are all with Popper's refusal to countenance orthodoxies or establishments of any kind, with science properly serving as an integral part of and support for the rational and critical Open Society. As much as I would like Popperian ideals to guide scientific practice, Fuller's attack on Kuhn seems to me a case of killing the messenger for delivering an unwelcome message about how science actually goes about its business. Science is like it is for reasons that have nothing to do with Thomas Kuhn, and it would be this way even if Kuhn had never been born. If the problem is the gap between Kuhnian reality and Popperian ideal, then the important question is how to get from the one to the other. Fuller's suggestions about that are pathetically weak. For example, he notes that "Paul Feyerabend advocated the devolution of science funding from nation-states to local communities as the surest way to increase science's capacity for good and lower its capacity for evil." When Fuller refers to the voicing of this fantasy as a "public intervention by a philosopher of science," you don't know whether to laugh or cry. Even if you accept Fuller's ideological commitments, he fails to describe any credible scenario by which modern science, with its vast funding requirements, its national security role, and its industrial entanglements, could conceivably be transformed into the kind of enterprise that he, and Popper, would approve of.

Very New Look at Old Debate

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

People already interested in this book because of its topic may well be under the misapprehension that Kuhn marked a progressive moment in the history of our understanding of science. This is completely wrong, says Fuller. If anything, Kuhn legitimized the idea that science should be subject to one dominant paradigm, excluding all alternatives. From that standpoint, it's easy to see why he testified for the intelligent design people since Darwinism is a closed shop in biology -- and isn't even treated as falsifiable (which is Popper's point). Make no mistake: This book isn't a simple Dummy's Guide to Kuhn and Popper like some of the other books mentioned by the commentators here. No, it's a thinly disguised polemic against the state of science today -- and it succeeds very well in that conscious-raising exercise.

Fuller Goes for the Jugular!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Those of you familiar with Fuller's magnum opus, Thomas Kuhn: A Philosophical History for Our Times, will know that this guy pulls no punches when it comes to passing judgments on people and events. This time he's decided to strip down all the footnotes and present the case straight -- Kuhn was a coward, at least by Popper's standards. Now, those of you who have read this far might wonder why should anyone care, since these are just a couple of philosophers of science. However, it goes to the issue of just how seriously these people took their ideas. As Fuller presents it, Kuhn had the luxury of working in elite institutions and took full advantage of it -- ignoring the larger world, even though it was engulfed in a 'military-industrial complex' largely driven by science, of which he was the most famous theorist. The rest of his contemporaries (notably Popper and his students, not all of whom were leftists) decried the use of science in this fashion, typically by appealing to their own theories. But Kuhn kept quiet. Luckily America won the Cold War, and so the comparison with Heidegger that Fuller raises at the end of the book now seems far-fetched. But that's the only reason it seems far-fetched. I'm amazed how easily people can let Kuhn off the hook. The relevant point of judgment is not what one now thinks with 30-40 years of hindsight but what one would have made of Kuhn's inaction back in 1970. It's too easy to excuse people's cowardice when the world turns out OK inspite of their inaction. By the way, for the record, Fuller is an American and if being younger disqualifies you from making historical judgments, then I think we're all doomed to everlasting ignorance.

The Kuhn paradigm, among other paradigms

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

This is a very good, and somehow hilarious, account of the debate between Popper and Kuhn, with its resemblance to another well-known debate, that between Popper and Wittgenstein. The author of a recent intellectual biography of Kuhn returns to the fray here, with a somewhat acidic critique of Kuhn's influence on the methodology of science. Fuller seems to side with Popper here, up to a point, and exposes the confusing and not always healthy influence of Kuhn's thinking on a whole generation of thinkers who never quite understood who Kuhn was, or the ambiguities of his background.