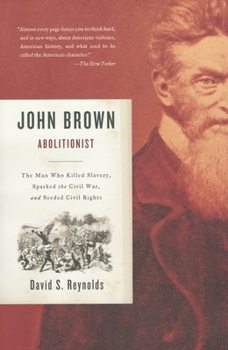

John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

An authoritative new examination of John Brown and his deep impact on American history.Bancroft Prize-winning cultural historian David S. Reynolds presents an informative and richly considered new... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0375726152

ISBN13:9780375726156

Release Date:November 2006

Publisher:Vintage

Length:592 Pages

Weight:1.20 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.1" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A Balanced and Subtle Portrait

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This book is one of the best biographies I have read on Brown, or anyone, for that matter. It is a subtle portrayal of a polarizing figure in American history, which does not condone Brown's behavior but tries to explain it based on the culture of the time and the life experience and beliefs of the man himself. Reynolds highlights particularly the religious beliefs that lay behind Brown's near-fanatical belief that slavery was an abomination. Reynolds also goes out of his way to focus on the fact that, unlike other Abolitionists of his time, Brown believed in equality - true equality - not just for slaves, but for women and other minorities. Brown, like Abraham Lincoln, believed in the words of the Declaration of Independence, that "all men are created equal." But Brown, unlike almost any other white man of his day, lived those words, as well. Brown's violence is highly problematic, but Reynolds argues that Brown felt there was no other way to combat the pro-slavery forces (much as many people today feel that violence is the only way to combat international terrorism). Reynolds does not white wash John Brown, but he tries to understand the man and his actions, to paint a balanced portrait of a controversial figure. This is a well-written and thought-provoking book, and I would highly recommend it to anyone interested in Civil War history or just looking for a good, if challenging, biography.

"I have only one death to die, & I will die fighting for this cause"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

John Brown is an American enigma. His life presents a serious challenge to a simple black and white interpretation of ethics, history, and by extrapolation, even current events. He was a man a hundred years ahead of his time in racial ethics - not only opposed to slavery, but unlike almost all other abolitionist of his time, actually a believer in the equality of the races. He was praised honestly by Ralph Waldo Emerson, who wrote of him that he "believed in two articles - the golden rule and the Declaration of Independence." Another contemporary, the black reformer Charles H. Langston praised him saying, "he was a lover of mankind - not of any particular class or color, but of all men...he fully, really and actively believed in the equality and brotherhood of man. ...He is the only American citizen who has lived fully up to the Declaration of Independence." Yet this man who was so dedicated to racial justice was able to direct the cold blooded murders of five pro-slavery men in Kansas who he had ripped from their families in the middle of the night and hacked to death with broadswords without any qualms or regrets. He chillingly stated that "it is better that a whole generation of men, women, and children should be swept away than that this crime of slavery should exist one day longer." Brown's life presents an open question on what if any limits should stand in the way of those attempting to right great societal wrongs and bring about justice. David Reynolds biography may not fully answer that question, but it goes a long way toward putting it into a proper perspective. Reynolds' biography of Brown is both detailed and fascinating, and is sympathetic without attempting to hide the dark and troubling aspects of Brown's actions. He delves deeply into Brown's Puritan heritage and just what that meant to his life and actions. He makes clear what a unique individual Brown was. While most of the famous abolitionist who were his contemporaries never questioned the basic racism of their time despite their opposition to slavery, Brown believed firmly in racial equality. Black men and women dined with his family, and he worked intimately with them, giving them real positions of authority in the endeavors that he organized - actions unique for his time. Reynolds also explores the fact that Brown was in favor of equal rights for women and humane treatment of American Indians. He notes that while he was a fervently committed Calvinist Christian, he worked closely with others who did not share his faith, including Jews and agnostics. He shows us a man who was not a typical fanatic, but a man who believed fanatically in one basic principle - the literal interpretation of the Declaration of Independence and the Golden Rule. Reynolds also puts Brown's most troubling violence, the murders at Pottawatomie, Kansas, back into the historical context in which they happened. He writes, "Pottawatomie, gruesome and vile as it was, was John Brown's impulsive response to

A Blow Against the Confederate Bias in History

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

This is a brilliant rendering of both John Brown's life and his great and inpenetrable significance in United States history, a significance that for generations was suppressed by an unreconstructed Confederate-white southern bias that still persists in mainstream history. It is an important corrective. At the time I write this, two reviewers -- I cannot call them "readers" since both indicate that they have not perused the book -- attack Reynolds as an apologist for Brown and his actions during "Bleeding Kansas." Typical of the Southern white bias (I emphasize "Southern white" only to indicate that much of the South was African American, so it is neither accurate nor proper to refer to the South as a monolith) neither acknowledges what brought those presumably "innocent" southerners to Kansas territory. They were there to bring human slavery to the west. They were there to extend anti-democratic, tyrranical, and criminal (what else can it be if one deliberately steals the labor of another) systems of unfreedom to the west. The ante-bellum period was not comfortable with the self-centered vision of God that permeates our present day culture. A few blocks from my home in Denver a church has attributed this to the Bible: "God Bless America, America Bless God." In Brown's time and before, the people assumed that a God of the Old Testament -- a God of vengence and divine Justice -- took an active hand in the affairs of men and nations. This was Jonathan Edwards' vision. This was Jefferson's as well when he wrote on slavery in NOTES on the STATE of VIRGINIA: ". . . can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? They are not to be violate but with His wrath?" Jefferson continues, with language as profound as any that appears in the history of the United States: "Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever; that . . . a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events; that it may become probably by supernatural interference!" He continues: "The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us [slaveholders against slaves, tyrants against the oppressed, the oppressor against the unfree, the thief against his victim] in such a contest . . . " Jefferson and David Walker were in agreement: ". . . but I tell you Americans! that unless you speedily alter your course, you and your Country are gone!!!!! For God Almighty will tear up the very face of the earth!!! . . . . I hope that the Americans may hear, but I am afraid that they have done us [African Americans, both slaves and free blacks] so much injury, and are so firm in the belief that our Creator made us to be an inheritance to them forever, that their hearts will be hardened, so that their destruction may be sure. This language, perhaps, is too harsh for the Ameri

Turning the tide of abolitionism

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

John Brown has suffered too long from the orchestrated neglect that biased history has imposed on him. Little more than a detail in passing in most histories of the Civil War, zooming in on the facts, as here in this excellent account, brings out his great importance in changing, and polarizing, the public perceptions of slavery just prior to the onset of the Civil War. We don't need to hide his contradictions, such as his violence in Kansas, to appreciate the remarkable complexity and depth to the man, despite the vagaries of his life and career. As one of the first truly non-racist abolitionists he deserves a major place in the cultural histories of racism. But most of all is his significance in turning the tide of pacifism predominant among abolitionists of his time, facing up to the reality the proslavery position implied. We may demur, but the American system was diseased at this stage, and what Brown did created a turning point at the ugly moment when the great democratic republic was effectively paralyzed by useless politicians stuck in their compromises, as with the Fugitive slave law, Dred Scott, and the racist hooliganism in Kansas (which drove Brown over the edge). Clearly political leadership at the moment of crisis was bankrupt and we see the forces of change emerging from figures such as John Brown.

The best book on John Brown, by far!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Read this book, and you will be converted to John Brown. You will also be entertained, since the book reads like a riveting novel. David Reynolds shows that Brown, a conscientious objector against military service in his young manhood, reluctantly turned to violence as a result of proslavery atrocities. Reynolds demonstrates that it was the institution of slavery--not John Brown--that began the violence. John Brown rightly saw that slavery itself was a state of war against an entire race. Could the freedom of nearly 4 million enslaved blacks have been delayed a moment longer? Should the emancipation of blacks have come a century later, as Abraham Lincoln said in 1858? No way. John Brown said that the "crimes" of his "guilty nation" could only be "purged away through blood." How prophetic. It took the death of more than 620,000 Americans to get rid of slavery. To quote W.E.B. DuBois, "John Brown was right" by forcing the issue of slavery. And David Reynolds is right in defending him. Reynolds points out that most other Abolitionists were racists. Lincoln several times said that since blacks and whites could not live on equal terms in America, blacks, once freed, should be shipped to Liberia or Central America. Jefferson felt that same way. The antislavery orator Cassius Clay said that the place for blacks was in the tropical sun eating bananas. The antislavery scientist Louis Agassiz argued that the typical black had the brain of a 7-month white fetus. And these were the ANTISLAVERY leaders! The South, meanwhile, believed that slavery was a noble, Christian institution, good for both blacks and whites. John Brown was different. He believed in a totally integrated America in which blacks, whites, and people of other ethnicities lived on equal terms. It's not Washington or Jefferson (both of them slaveholders) we should be remembering with veneration; it is John Brown.