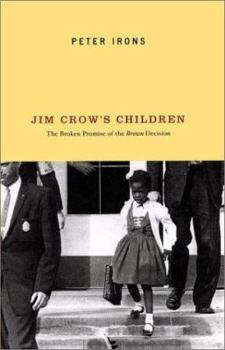

Jim Crow's Children: The Broken Promise of the Brown Decision

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court sounded the death knell for school segregation with its decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. So goes conventional wisdom. In fact, writes Peter Irons, today many of our schools are even more segregated than they were on the day when Brown was decided. In this groundbreaking legal history, Irons explores the 150-year struggle against Jim Crow education, showing how the great victory over segregation was...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0670889180

ISBN13:9780670889181

Release Date:September 2002

Publisher:Viking Books

Length:376 Pages

Weight:1.55 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.3" x 9.3"

Related Subjects

Africa African Americans African-American & Black African-American Studies Arts & Literature Authors Civil Rights Civil Rights & Liberties Discrimination & Racism Education Education & Reference Education Theory Educational Law & Legislation Ethnic & National History Law Legal History Political Science Politics & Government Politics & Social Sciences Race Relations Reform & Policy Schools & Teaching Social Science Social Sciences Specialties Specific Demographics Specific Topics TextbooksCustomer Reviews

2 ratings

Good History, So-so Social Analysis

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

In high school, college and to some extent in law school, the Brown decision was presented as some sort of cultural epiphany during which our nation woke up and realized that racial classifications were wrong. Although the Brown decision certainly marks a turning point in race relations as well as constitutional jurisprudence, it is less national self-realization than the culmination of concentrated efforts of numerous brave individuals. The book is accessible to lawyers and laypersons alike. Irons does an excellent job of avoiding "legalese." Where legal terms are necessary, he explains them. His writing is clear and to the point. Irons opens by discussing the concentrated efforts to prohibit black slaves from receiving an education. He shows how depriving education was a powerful and effective weapon in the racist arsenal. He touches briefly on the Dred Scott and Plessy v. Ferguson decisions to set the stage. More importantly, however, he introduces the readers that are not overly familiar with legal education to Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents. These two decisions addressed integrating post-secondary education and were decided before Brown. They also show that Brown was a gradual progression and that Plessy was eroded slowly. His insight in to 19th Century attempts at school integration is enlightening. Brown and its companion cases were not cases of first impression (the first time a court decides an issue). When the NAACP tried to integrate schools, it had numerous judicial opinions against it. The NAACP legal team, headed by Thurgood Marshall, made calculated attacks on school segregation to set the issue up for review by the Supreme Court. Irons penetrates the secrecy of the Supreme Court to give us a glimpse of how Brown was decided. Of particular interest is how Earl Warren worked to achieve a unanimous court. Some readers will no doubt be surprised to learn that school integration was not the foregone conclusion we think of it as today. The real value of the book comes when Irons moves in to the post-Brown era. He examines the battle between the federal courts and state governments to implement the Brown decision. His discussion of the busing cases is excellent. For those who think that the battle over school integration ended, his analysis of the current court's resegregation cases will be eye opening. The main critique of other reviewers appears to concentrate on his conclusion that integrated education is the magic bullet of race relations. I agree with his conclusion that integrated education will assist in that area, but the support he cites is not adequate to get to there. In other words, he bit off more than he can chew. It is a tough job to write a generally accessible book making social conclusions based on in depth academic studies. When he cites statistics, it gets a bit confusing. I think the general reader's attention will wander which hurts his point. Rather than end th

Very well done though I had two qualms

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

This book is clearly the result of a great deal of thought and effortand I recommend it to anyone interested in the subject. It really causes one to question the commonly held assumption (at least perhaps among whites) that all of the issues involving forced segregation and the negative consequences that flowed therefrom more or less evaporated in 1954 or shortly thereafter. Quite to the contrary, the book shows how, in may ways (though obviously not in all), there are almost more similarities between the state of American education and race relations between, say, 1953 and today than there are dissimilarities. In that sense, the Brown case may have accomplished a whole lot less than is commonly imagined. For this reason alone, the book is valuable. I did have two qualms with the book however. The more trivial one is that I thought that the numerous statistics were confusingly presented, perhaps because the author tried to summarize them in prose rather than in charts. There were repeated times that I had to re-read those portions of the book and I feel that that was mostly because the author did not do a good job of clearly summarizing the statistical information for his readers. I feel that the use of charts would have been more helpful (and perhaps more dramatic as well in terms of proving the author's points). My other complaint goes to the issue of the remedy to the problem. It seems to me (and I think that the author concedes as much) that a good portion of the reason for the problems that exist today relate to changes in demographics, culture and societal forces which are beyond the power of the courts or the legislature to change--just as some judges and commentators have stated. To be sure, these changes include white flight to the suburbs, but nevertheless people live where they live and little can be done about that. Thus, in that sense, to the extent that most children attend schools in which their own race predominates (as in the pre-Brown days), I'm not sure that I would call that a "failure" or a "broken promise" of the Brown decision. The author seems to take this point as a given, but then proceeds to say that we should not give up; that we should keep trying to fulfill the promises of the Brown case notwithstanding that; that we should search for the harder solution. One possibility for that solution is of course a modified "separate but equal" solution in which separation still exists (though for societal reasons and not due to legally sanctioned segregation) but this time with true equality in terms of funding, teachers, facilities, etc. In other words, make the black schools just as good as the white schools. Irons seems to disapprove of this solution on a number of grounds, and I tend to agree with him. As Thurgood Marshall stated, the idea and the ideal is true integration between the races and NOT separate but equal, even if there were true "equality" in the senses I have stated. Bu