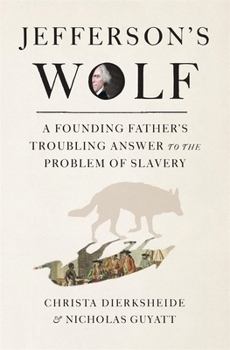

Jefferson's Wolf: A Founding Father's Troubling Answer to the Problem of Slavery

A decisive reassessment of Thomas Jefferson's long-debated views on slavery, showing that his chief antislavery strategy was racial exclusion: the removal of emancipated Black people from the United States.

Toward the end of his life, Thomas Jefferson made his most famous statement about American slavery: "We have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go." Presenting abolition as both necessary and perilous, the remark has long been relied upon to explain an apparent paradox: despite publicly opposing slavery for four decades, Jefferson had made no progress toward Black freedom in his political career by the time he died in 1826. Nor had he done so in his expansive household, where he enslaved more than 600 people, including Sally Hemings and the four children he fathered with her. Christa Dierksheide and Nicholas Guyatt argue that the key to understanding Jefferson's antislavery position is his commitment to racial exclusion. Jefferson believed that the principal reason to abolish slavery was the threat of a massive slave revolt, but he viewed the presence of free Black people in the new nation as no less dangerous. To avert racial violence, Jefferson argued, the gradual abolition of slavery had to be paired with Black exile. Even when challenged by white and Black contemporaries with more expansive views of American belonging, Jefferson held fast to his vision for a white republic. Neither an egalitarian antiracist nor a proslavery apologist, Jefferson became the most influential advocate for racial separation in the early United States. Charting the evolution of his thought across the nation's formative decades, Jefferson's Wolf is a surprising and provocative account of the problem of slavery in the founding era.Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0674278321

ISBN13:9780674278325

Release Date:May 2026

Publisher:Belknap Press

Length:272 Pages

Related Subjects

HistoryCustomer Reviews

0 rating