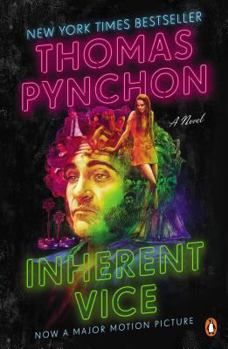

Inherent Vice

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Part noir, part psychedelic romp, all Thomas Pynchon--Private eye Doc Sportello surfaces, occasionally, out of a marijuana haze to watch the end of an era In this lively yarn, Thomas Pynchon, working in an unaccustomed genre that is at once exciting and accessible, provides a classic illustration of the principle that if you can remember the sixties, you weren't there. It's been a while since Doc Sportello has seen his ex- girlfriend. Suddenly she...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0143126857

ISBN13:9780143126850

Release Date:November 2014

Publisher:Penguin Books

Length:384 Pages

Weight:0.76 lbs.

Dimensions:0.8" x 5.4" x 8.4"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Related Subjects

Contemporary Fiction Literary Literature & Fiction Mystery Mystery, Thriller & Suspense RomanceCustomer Reviews

5 ratings

Manson & Nixon

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

"It was like finding the gateway to the past unguarded, unforbidden because it didn't have to be. Built into the act of return finally was this glittering mosaic of doubt." Imagine a surfer-noir novel set in L.A. and environs in the spring of 1970 by Thomas Pynchon. Could anything be better? Answer: Inherent Vice is better! It's everything you could imagine, and then some. Every sentence is hugely entertaining, sort of the way Cormac McCarthy is entertaining, and also P.G. Wodehous. You just relish the diction. The plot is pure Chandler in its schematics: that is, characters are multiplied unnecessarily all for the dazzling color they give to the story; plot trots behind trying to keep up and just about succeeds in catching every character before they hit the ground. As in Chandler the characters who matter sort of only slowly emerge from the carnival, some very late: but that's the point of a carnival. Everyone matters to some gum-shoe or -sandal: we're concerned here with the ones that Marlowe or Doc are concerned with. And Pynchon is so different from the writers I've lately been thinking about, writers who narrate the experience of narration. Reading Pynchon is a little like reading Shakespeare or Hammett: I'm just a wide-eyed reader again, not a person figuring out the experience of writing this book. I mean I am that sort of audience too for fun TV and Elmore Leonard and Neal Stephenson, for example. I like being just that. But for TV or Elmore Leonard I like because I can just enjoy the easy enjoyment of the thing. Whereas Pynchon requires -- no he doesn't require, he REWARDS -- the same kind of concentration I give Woolf or Geoff Dyer: a lot of concentration. But there's something wonderful about not concentrating on the experience of the book as an act of writing. You just concentrate for your own pleasure. And, man, he writes a good last line. It's not that Pynchon as writer isn't an issue in the book. He is. But he's astonishingly good natured as a writer. What other real writers are? I can't think of any, not even Fielding. Anyhow the first half of the book (when it's explaining something) repeats very occasionally -- sparsely even -- and very hauntingly two versions of the same phrase: "in those days"; "at that time." This plus a reference to Vineland as a place, plus one bracketed movie date at the end, are the only authorial self-references, the only sense that you have that an author is telling this to the reader instead of the voice coming off the page as part of the laid-back generosity of the narrative atmosphere. I love those phrases. They disappear from the second half, which is part of the very sadness the book's about: the end of an era, with Manson & Nixon (Doc must be called Doc partly as a descendent of Mason's, one of whose sons is called Doctor Isaac.) Doc is slightly younger than Pynchon himself, pushing thirty in 1970, as we learn in a great, casually sad passage: "Plastic trikes in the yards, pe

What's So Funny About Peace, Love, and Understanding?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

As many have already written, Thomas Pynchon is an acquired taste, like jazz and silent comedy (two other tastes I have joyfully acquired). I first tasted Pynchon, like most readers my age, in his debut novel, "V." Somewhere between the silliness of the "whole sick crew" and the all-too-seriousness of Stencil's Oedipal search, I realized I was reading someone who was a literary personification of a Jerry Garcia dictum: "It's not enough to be the best at what you do. You have to be the only one to do what you do." I was (am) hooked. Not that Pynchon hasn't let me down. I did not like "Against the Day" after page 250 or so (or once we left the Colorado miners behind), and "Vineland," I thought, was a bad joke. "Gravity's Rainbow" is probably still his best, but for warmth and humanity, "Mason & Dixon" tops it. Many reviewers are already referring to his new book, "Inherent Vice," as his warmest, but I still vote for Charles & Jeremiah. What "Inherent Vice" is, is a wonderful joyride. It probably doesn't hurt that I was an idealistic hippie in the spring of 1970, somewhat younger than protagonist Doc Sportello, but just as disgusted with what Pynchon calls "flatland." There are the usual Pynchon foibles - too many stupid names, too much loveless sex, too many bad punchlines. But there is something so easy about reading it - and that is certainly unusual for Pynchon. I'm not sure if all readers will have as easy a time as a Pynchon devotee like me, but I don't see how this novel could present any real difficulties. Just remember that plot continuity is not really all that important in any PI novel. Raymond Chandler agrees with me on that last point, and Pynchon is obviously lovingly parodying Chandler and Hammett in "Inherent Vice." The greatest element of the novel is the aforementioned Doc Sportello, who, although referred to in the third person, is the narrative point of view through which the tale is told. We see all of Gordita Beach and Greater Los Angeles through his pot-clouded senses. Doc shares something with all of the great detectives of the genre like Chandler's Philip Marlowe or Hammett's Continental Op -a code of honor. In Doc's case, he is loyal to the hippie subculture that is trying to eke out an existence by the waves instead of joining the decrepit and meaningless straight world. As one character puts it, the tug is between the hippie lifestyle of "freedom" vs. "that endless middle class cycle of choices that are no choices at all." Doc sees that his and his friends' way of life has a short expiration label, but he does everything in his power to keep it running as long as it can. And, of course, in the spring of 1970 in L.A., it was running out quickly, what with Manson and his family, who are eerily in the background throughout the novel. I won't give anything away. I will tell you that Pynchon's novel, if not his warmest, is definitely his most comic. I mentioned earler that there are too many flat

A Gateway Drug to the Harder Stuff

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

I always used to think of "The Crying of Lot 49" as the obvious entry point to the work of my favorite author. It may have had some dense prose, but at least it was short. A new portal has been opened. "Inherent Vice" is both short and easy to read, but it's still recognizably the work of Thomas Pynchon even if the pink flaps of the dustjacket are visually jarring as you read the remarkably unconvoluted sentences and short paragraphs. Despite the surprisingly atypical cover ("Mason & Dixon" and "Against the Day" appear so large and beige and sober on my bookshelves), pot-smoking private eye Doc Sportello would have felt at home wandering through any other book in the canon. I'm hoping that some new readers will pick up this quick marijuana-fueled trip through 1970 Los Angeles (a place where Pynchon seems very comfortable) and move on to the harder stuff, especially "Gravity's Rainbow," which may now seem much less daunting than its reputation. (I can't help thinking about James Joyce. How much less intimidating would his comic masterpiece "Ulysses" have seemed to many readers today if Joyce had ended his career with a simple thriller set in Dublin rather than with "Finnegans Wake"?)

Farewell My Lovely

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Those that know, know the writing of Thomas Pynchon can be a rough row to hoe--featuring convoluted, paranoid plotting, byzantine sentence structure, alternation of genres and modes of presentation within a single opus--sometimes even a single page--funny names and multi-layered puns, revisionist history and anachronisms galore. And pizza--plenty of pizza. What most folks who've read Pynchon expect is a rough but rewarding time decrypting encoded messages pointing to vast conspiracies both right and left, and being able to pat themselves on the back for being so wickedly erudite as to be able to follow at least some of the multiple, overlapping plotlines found within each of his six novels. Those that don't know Thomas Pynchon usually bail out on page 150 of Gravity's Rainbow. But note this down and burn this deep into your collective forebrains--Inherent Vice, Thomas Pynchon's seventh and funniest novel, is a beach read. The grand master of literary obfuscation actually did it this time--either he made a conscious decision to express himself via comparatively stable characters and plotline of a more traditional make & model or he said "screw it--it's time to cash in!" Inherent Vice has sentence structures and vocabulary more akin to Tom Robbins than Henry James, an overall shape more like Christopher Buckley than Henry Adams. You'll knock this one back like chugging down a Corona during a Fresno mid-summer heat-wave. Inherent Vice is cool and refreshing and funnier and easier to comprehend than anything else Pynchon's written so far. And yes folks, in spite of various smack-downs from some of the more self-conscious members of the professional lit-crit establishment, Inherent Vice has meaningful connections to Pynchon's larger collection of cabals and conspiracies including a lot of what appears to be the author's personal back story. There is a major element of autobiography to this novel, a Palimpsest buried in so deep that it's more like a solid concrete foundation--you'll need some heavy-duty construction equipment to work your way through it. Once I opened the book I knew that this stuff had to be ripped from the tattered casebook of Thomas Pynchon, professional cryptic `n sleuth--from cloak and dagger to croak and stagger!!! I was seeing where stuff in Gravity's Rainbow could have come from--what lunch might be like Under The Sign Of The Gross Suckling, places where you'll find boysenberry yogurt and marshmallows on your pizza --or a joint along with your hamburger available during Tommy's Hamburger's 2-4-1 special. No fear dude, this little pamphlet will be plenty re-readable, with loads of evidence of mindless pleasures to unearth as you dig through the narrative rubble. While many readers of Inherent Vice will note the resonances to The Big Lebowski, & some to the Robert Altman/Elliott Gould "Long Goodbye"--fewer still recalling "Nick Danger, Third Eye" and an even more miniscule slice of that demographic recalling Bonzo Dog B

An Exuberant Romp Through the Psychedelic 1960s

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

4.5 out of 5: Cloaked as a detective thriller, Inherent Vice contains the snappy dialog, complicated plot, and criminal underworld types typical of the genre. Don't be fooled by the packaging, though. This novel is pure everything-including-the-kitchen-sink Pynchon with satirical song lyrics, paranoia, drugs, pop culture, lawyers, sex, politics, zombies, more drugs, and a side-trip to Vegas. The neat resolution of a convoluted plot is not really the point. Instead, let go of your need for closure and join Pynchon for a buoyant romp through the psychedelic haze that was L.A. in the late 1960s. Doc, an amiable, drug-addled personal investigator, stumbles onto a vicious international crime ring as he works on a case brought to him by his ex-girlfriend. By turns brilliant and bumbling, Doc exudes a kind of humble innocence and is the likeable center of this novel. He's both trustworthy and trustful and never far from questioning his own abilities and actions ("Did I say that outloud?"). In a typical example of the endearing workings of Doc's logic, he tries to deduce the origin of a postcard he receives "from some island he had never heard of out in the Pacific Ocean, with a lot of vowels in its name": "The cancellation was in French and initialed by a local postmaster, along with the notation courrier par lance-coco which as close as he could figure from the Petit Larousse must mean some kind of catapult mail delivery involving coconut shells, maybe as a way of dealing with an unapproachable reef." In Doc's world, postcards delivered via coconut catapults make perfect sense. Clearly, Pynchon is having fun with the detective genre. In one scene, Doc drives to a mansion protected by a moat with a drawbridge. After the drawbridge descends "rumbling and creaking," "the night was very quiet again--not even the distant freeway traffic could be heard, or the footpads of coyotes, or the slither of snakes." Beneath all the humor and satire, there's a darker message here. The fun is almost over for Doc and his fellow hippies as paranoia, the harbinger of future oppression, overtakes the fun-loving sixties "like blood in a swimming pool, till it occupies all the volume of the day." At times Inherent Vice is overly constrained by its purported genre as Pynchon weaves together the complicated plotlines of a detective story, maintaining too tight a grasp on a linear reality. The excessive plotting hampers some of the book's whimsical exuberance. But, unlike much of Pynchon's previous work, Inherent Vice is eminently readable and even, at times, actually suspenseful. At under 400 pages, Inherent Vice is also one of Pynchon's shortest novels. If you've been too intimidated to attempt a Pynchon novel up to now, try this one.

Inherent Vice Mentions in Our Blog

20 Great Album-Book Combos

Published by Ashly Moore Sheldon • April 20, 2023

Find the perfect music to complement your reading experience? Or vice-versa! Here are twenty vinyl albums (worth double points from now until 4/23) with a reading recommendation for each.