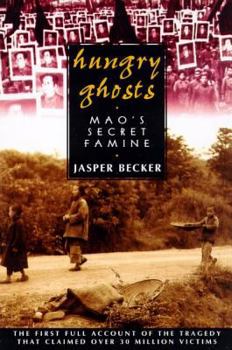

Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Chinese people suffered what may have been the worst famine in history. Over thirty million perished in a grain shortage brought on not by flood, drought, or... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0805056688

ISBN13:9780805056686

Release Date:April 1998

Publisher:St. Martins Press-3PL

Length:416 Pages

Weight:1.23 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.9" x 8.9"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The greatest peacetime disaster of the 20th century

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

----------------------------------------------------------- A horrifying and well-researched history of how Mao's "Great Leap Forward" became the worst famine in history, killing perhaps 30 million Chinese (1958 - 1960) -- it appears unlikely an exact fatality figure will ever be known. Which adds to the horror, I think, that millions of people, with hopes and dreams like our own, could vanish without leaving a trace, even a number, in the world outside their homes. Not to mention uncounted millions of children whose lives were blighted by brain-damage from malnutrition.... FWIW, Jasper concludes that Mao's Great Famine was more omission than commission (in contrast to Stalin's): Mao's absurd ideas of backyard industrialization, plus turning loose the Red Guards chaos, ruined the harvests. Then Communist Party officials simply denied the problem, and concocted elaborate coverups -- even painting the tree trunks to hide that the bark had been eaten by starving people -- when Mao or senior officials were to visit famine areas. And a smiling-peasants "Big Lie" for foreigners, which worked for years. It's a remarkable, and depressing, account. Highly recommended. review copyright 1999 by Peter D. Tillman

Read it and weep

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I immediately recognized the photo on the cover of Hungry Ghosts, a boy and two women (one carrying a baby) pulling a plow. When I first came to Taiwan, a few days after Lin Biao died and a few weeks before Nixon visited Mao, the government here frequently published this photo as evidence of how wrong things had gone in the PRC. Pooh, I thought, things can't possibly be as bad as they said. For proof I looked to the glowing reports published by the first American reporters to visit: one even brought along her father, who had been a missionary, and could speak some Chinese. Years after Mao died, when the PRC started opening up, it became evident that the KMT had vastly understated its case, perhaps to avoid panic here. Hungry Ghosts documents a tragedy that the world hardly noted. I would be the last to claim expertise on PRC government affairs, but one reason I believe Hungry Ghosts is credible is that detail after detail meshes with bits and pieces I had picked up over the years, unaware of the extent of the disaster. Example: Becker mentions the dams peasants had to build. In the early 1980s, Mr Wei, from a family of tea farmers in Fujian, told me why his relatives starved:"We were told that tea is decadent and capitalistic. We were ordered to tear out all the tea trees and plant grain. Our family has farmed those hills for generation after generation. We know the soil, we know the climate, and we know that grain cannot grow there. We were ordered to build a dam. We didn't know how, so we asked the cadres. They said,'Ask an old farmer.' We had no choice, so a couple old farmers got together and planned a dam, even though they had never seen one, either. We toiled and toiled. Since we were producing no crops, we had little to eat. Finally, our dam was finished. As soon as we let the water flow, it washed away the dam. We asked the cadres what to do. They said, 'Grow tea.' But we couldn't harvest tea for several years. For three years, we had nothing to eat. Many of my relatives starved." Anybody who reads Hungry Ghosts will recognize the elements in this story. For me, practically the whole book reads like this, corroborating things I had seen and heard over the years. Mr Becker speaks with authority on modern China, but his ancient history is weak. The first chapter opens with "an inscription on a Shang tomb." I have never heard of an inscription on a Shang tomb. In, yes; on, no. If the inscription is translated correctly, it is hardly typical of early Chinese thought (unless the 'Emperor' refers to the god Di). Becker makes some outlandish comments about Confucianism. Okay, big deal, his book is about modern, not ancient China. His explanation that the Cultural Revolution was a response dealing with the GLF makes sense of an otherwise senseless convulsion. Dear reader, this is a heart-breaking book. May you and I never suffer as those poor people suffered. May such times never come again.

An Astonishing, Horrifying, Catastrophe...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

It has often been said that, to understand China, you must know of its past. Here is a compelling treatment of a chapter in China's history that is almost a black comedy. Mao's Great Leap Forward is predicated upon such preposterous silliness that we chuckle at its absurdities (eg, the crops will improve with "deep planting" at up to 12 feet; steel can be made by all in back yard smelters, etc...). Yet...the consequences are so awful, that any thought of smiles is quickly erased.Historians differ, but here was want and famine on a scale unprecedented in the 20th century. Perhaps as many as 30,000,000 died. Another reviewer scoffs at this number and says that it was "only" 10,000,000. Whatever the number, this is still an unthinkable tragedy, and one that happened in our lifetime. Like the Taiping Revolution that claimed as many as 22,000,000 lives (read "God's Chinese Son"), it left an indelible, but largely unknown mark on China - one that shapes the country today as it emerges as the only "other" super power.Well written and fascinating.

Nice Job, Excellent Read

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

I found this book well-written, well-organized, and moving. It's interesting to see how many Chinese readers consider it ethnocentric and anti-Chinese. I didn't take it that way at all -- Mao's sort of madness is all-too-universal in human history, and the story left me with a sense of great admiration for the Chinese people who somehow suffered through this period. Becker is also very careful to point out that the real roots of the disaster were not in China but in Mao's enthusiasm for actions of Stalin and the writings of Marx.And if the portions on Mao sometimes read like a bio of Idi Amin, well, I'd consider that appropriate. He was a murderous, vainglorious sociopath. The fact that he was right about the terrible crimes of the Western powers against China neither changes nor justifies a thing. Anyway, a very nicely written and fascinating account that left me wanting to learn more about both ancient and modern Chinese history.

Free markets vs. government planning

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

I have taught finance at universities in both Hong Kong and the US, and I regularly recommend this book to my MBA and undergraduate students as a graphic illustration of the risks and weaknesses of a planned economy, particularly when combined with control of the media. Perhaps Becker puts too much emphasis on the responsibility of Mao and not enough on his many followers. But the fact remains that this massive famine could not have occurred in a market economy and would not occurred if so much power had not been concentrated in the hands of one person. Mao was brilliant when it came to maintaining political power but painfully inadequate in his understanding of science. In power politics, reality is whatever you can convince people to believe. Mao refused to accept the fact that science and economics do not ulitimately follow this same rule (or perhaps he didn't care). No matter how many people claim to believe in a bountiful harvest, they will still starve to death if they have nothing to eat. To further understand the Chinese Communist Party under Mao, I recommend the book written by Mao's personal physician. As for Becker's account of the worst famine in history (and the postscript to the later edition, pointing out that it's happening again today in North Korea), the book is informative and fascinating. It offers a lesson for those, particularly in Asia, that don't believe that economic decisions should be left to the market. A government directing industrial policy is unlikely to produce the extreme consequences seen here. Nevertheless, the dangers of lack of diversification due to one set of possibly misguided or simply mistaken leaders forcing everyone in the same direction are the same. Too much attention is given to the relatively rare cases, such as Japan or Singapore, where it worked, at least temporarily. This is the most extreme of the many, many examples that show how painful failure can be when the same policy is forced on everyone.