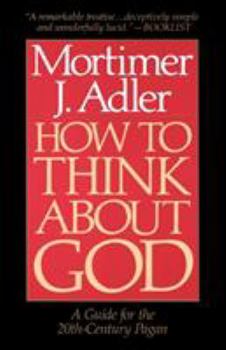

How to Think about God: A Guide for the 20th-Century Pagan

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Dr. Adler, in his discussion, extends and modernizes the argument for the existence of God developed by Aristotle and Aquinas. Without relying on faith, mysticism, or science (none of which, according to Dr. Adler, can prove or disprove the existence of God), he uses a rationalist argument to lead the reader to a point where he or she can see that the existence of God is not necessarily dependent upon a suspension of disbelief. Dr. Adler provides a nondogmatic exposition of the principles behind the belief that God, or some other supernatural cause, has to exist in some form. Through concise and lucid arguments, Dr. Adler shapes a highly emotional and often erratic conception of God into a credible and understandable concept for the lay person.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0020160224

ISBN13:9780020160229

Release Date:July 1991

Publisher:Touchstone Books

Length:180 Pages

Weight:0.67 lbs.

Dimensions:0.5" x 5.6" x 8.4"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A Helpful Beginning for Inquiry

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

For an erudite review, others will serve you better. I write as one who was raised in a deeply fundamentalist (very "non-pagan") religion, and who found the God espoused by it far too small to inspire awe.If you are looking for proof that Abraham's God exists, you will not find it here. However, as one who has only recently begun a serious quest to come to terms with the idea of God, I highly recommend this book. It has provided me a foundation for subsequent reading and instruction in the process of discriminative thought---both of which have proven very helpful as I continue seeking.

A Compulsive Argument for the Existence of God

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

I first came into contact with Adler's _How to Think About God_ some 20 years ago. For me the major portion of the book has been a compulsive argument for the existence of God ever since. The argument runs somewhat as follows. If the existence of the cosmos needs to be explained and if it can not be explained by natural causes, then it must be explained by supernaural causes. The existence of the cosmos is contingent; the present cosmos might have been other in its order and arrangement. The cosmos is a random one with a random number of dimensions. (I especially liked this part of the argument.) It is necessary to posit God as a preservative agent. For me this argument has been compulsive for about 20 years.In the epilogue, Adler goes on to say something very important and that is that natural theology has its limits. The nature of God, the place of humans in the cosmos, divine law and grace, etc. belong to sacral theology and " have no place in natural theology."

A new cosmological argument by a great thinker

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Mortimer Adler published this book as "a guide for the 20th-century pagan." At that time he considered himself a pagan (i.e. "one who does not worship the God of Christians, Jews, or Muslims"). As a prerequisite to his argument for the existence of God Adler assumes that the cosmos may be infinite in time. For, "to affirm ... that the world or cosmos had an absolute beginning --- that it was exnihilated at an initial instant --- would be tantamount to affirming the existence of God, the world's exnihilator." Adler wants to present an argument that "avoids the error of begging the question." Likewise he rejects the need for a first cause of the cosmos. A cosmos that has "an infinite extension of time from the present backward" can also have an "infinite temporal series of causes and effects."He rejects the "best traditional argument" for the existence of God, the argument from contingency, because the contingency we actually observe in the universe is only superficial, involving mere transmutation. Yet radical contingency, involving exnihilation and annihilation of entities, is what the argument presupposes. Adler supposes instead a principle of inertia of being. With inertia "bodies set in motion continue in motion without the action of any efficient cause...and...come to rest only through the action of counteracting causes." Individual things of nature may also be brought into existence by natural causes and continue so until the action of counteracting natural causes results in their perishing.Having rejected the third premise as traditionally understood Adler now recasts it. While radical contingency may be implausible of individual things in the cosmos, it might be true of the cosmos as a whole. What is true of the whole is not always true of the parts. Unlike the component parts that make it up, the cosmos does not exist as part of a greater whole. It therefore has an independent and unconditioned existence. It does "not dependent for its existence upon a larger whole to which it belongs, as its own parts do; and...its existence is not conditioned by factors outside itself, as the existence of individual things is conditioned by factors operating in their cosmic environment." The question then becomes is its existence caused or uncaused? Adler then states "the four propositions that constitute the premises of a truly cosmological argument:"1. The existence of an effect requiring the concurrent existence and action of an efficient cause implies the existence and action of that cause.2. The cosmos as a whole exists.3. The existence of the cosmos as a whole is radically contingent, which is to say that, while not needing an efficient cause of its coming to be, since it is everlasting, it nevertheless does need an efficient cause of its continuing existence, to preserve it in being and prevent it from being replaced by nothingness.4. IF the cosmos needs an efficient cause of its continuing existence to prevent its annihilation, TH

A Great Book.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This book is quite good. Adler's way of explaining is quite clear. He makes sure that every point is understood well enough for a common arm-chair philosopher (myself and all of you). He continually repeats his purpose and the main points and definitions so as to keep everything closeknit and tied together so that a definition or concept on page 2 isn't forgotten or lost by page 92 when it is really needed most. Any negative reviews will be by closeminded atheists and theists... the atheist because he actually does give us reasonable grounds for affirming the existence of God (the God of the Philosophers); and the theist because he doesn't go far enough in saying their God has real existence. I cannot understand how anyone can rip this book. It gives the atheist what he wants- an uncreated universe (at first) and gives the theist a God and even a brigde across the chasm between the God of the Philosophers and the God of Religion (finally)."Two Thumbs Up!"

Deceptively Simple

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 28 years ago

As the subtitle suggests, this book is intended "for those who do not worship the God of the Christians, the Jews, or the Muslims" (3). These are the people Adler calls Pagans. More specifically, Adler wants to reach the "open-minded pagans" (6). Citing Blaise Pascal for his definition of an open-minded pagan, Adler states that these are the people that "do not know God but seek him (6). After reading Adler I realize that he is probably overlooking a theological hari in order to build a bridge with the "pagan." This could be because he wrote this book before his conversion to Christianity (see Kelly James Clark, *Philosophers Who Believe* Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993 for the testimony of Mortimer J. Adler). The hair that I am speaking of is that although we know that men should seek God (Acts 17.27) we know that there are none that actually do see the true God (Romans 3.11b). Perhaps Adler has said too much here. Perhaps he should have simply stated that the book was for the open-minded. Secondly, this book is for the intellectually adept and not for the philosophically challenged. If the "pagan" does not have a basic background in these arguments they will have to read the chapters very slowly in order not to get caught in the web of points and subpoints contained in each chapter. Adler, a stickler for detail, posits a proof for each premise he makes. Thus he makes a very simple argument somewhat hard to follow at times. Adler even impatiently gives up on the reader if they cannot understand his first "self-evident" philosophical truth. This ponderous proposition states "The existence of an effect that requires the operation of a co-existent cause implies the co-existence of that cause." The point is very crucial to the whole argument and we do not want to frustrate the open-minded pagan at this point. Instead we want him to get this point. After explaining what he meant, Adler, lowering himself to intellectual snobbery, writes, "Very little can be done to remedy the deficient understanding on the part of the those who don't immediately see the truth of such propositions" (116). Such remarks can close an open mind very quickly. Thirdly, Adler's book posits a patina of universalism. Although I realize that Adler is trying to point the reader to a theistic point of view, I would refrain from saying "the God of Christianity, the Jews, or the Muslims" (3); or the "God of the Christians, Jews, and Muslims (3); or even worse "the God of Abraham, Isaac Jacob," (28) and "of Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed" (154). AFFIRMATIONS Hoping that I have not poisoned the wells, the above criticisms do not reflect the overall tone of the book. As one who has studied many of the best arguments for the existence of God I thought that I had a pretty good grasp on how to think about God. I approached this book thinking that Adler would simply repeat what I had read in most philosophy of religion books. to my surprise Adler tore down