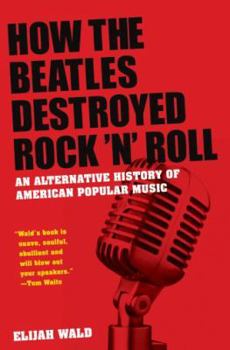

How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"There are no definitive histories," writes Elijah Wald, in this provocative reassessment of American popular music, "because the past keeps looking different as the present changes." Earlier musical styles sound different to us today because we hear them through the musical filter of other styles that came after them, all the way through funk and hip hop. As its blasphemous title suggests, How the Beatles Destroyed Rock 'n' Roll rejects the...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0195341546

ISBN13:9780195341546

Release Date:June 2009

Publisher:Oxford University Press, USA

Length:336 Pages

Weight:1.45 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 9.3" x 6.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Beatles? Who were they?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I figure I'll get my complaints out of the way first, starting with the terrible title. Yes, the media has pretty much reduced popular music history to (pick one) The Beatles, Elvis Presley, and Frank Sinatra, so it may be that, to get readers, an author has to name-drop one of those three. Imagine if the title had mentioned Earl Fuller, Paul Whiteman, Billy Murray, or Lawrence Welk--the volume might be gathering dust in a Big Lots bin as we speak. Still, "How the Beatles...." is so very misleading as to be a shame. Then again, if it succeeds in grabbing attention, more power to it. My second major gripe--Wald's assertion that mood music "would have made little sense without long-playing discs" (i.e., prior to 1948), since its main function was "to create a lingering, romantic ambiance." Well, no. Mood music originated as material for silent movies, the musical stage, and early radio, and it proliferated on disc--examples by Paul Whiteman, Erno Rapee, Domenico Savino, and Andre Kostelanetz are common items on eBay. Many of the staples of mood music are 19th and early-20th-century light works that were also staples of early sound recordings--"Narcissus," "To a Wild Rose," "Old Folks at Home," "In a Clock Store," etc. Finally, I can't help thinking that Wald has exaggerated the gap between early sound recordings and what was happening, performance-wise, outside of the recording studio. Granted, sound recordings provide a limited document, given the particulars of the medium (length, sonic limitations, the use of studio musicians, the recording process' lack of portability, etc.), yet I find no basis for presuming a huge disconnect between what we hear on 78s and what we might have heard "live," especially given that recordings initially followed from (and were necessarily derivative of) other media such as sheet music, pit band orchestrations, music hall sketches, etc. What I liked, on the other hand, could fill a book. First and foremost, Wald is to be praised for treating popular music as just that--popular music. As in, the music that people listened to, vice the music that critics think people SHOULD HAVE listened to. It's a sad comment on music journalism that it's taken this long for the concept of "popular" to take hold, but late is better than never. That his approach has been received as revolutionary is a bit scary, not least of all because it's true. Again, better late than never. And his coverage of the impact of rock and roll on jazz, etc. is the savviest account I've yet seen--yes, absolutely, beyond a doubt, rock and roll was seen at the time (by professional musicians, at least) as a triumph of amateurism, which it was to an extent. My jazz-musician father and his friends expressed this view again and again over the years, and even as a kid I could hear the difference in competence between the jazz on my parents' hi-fi and the rock on the radio. My father did surprise me at one point by describing rock and roll

Bad title, good book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Even at first glance, Elijah Wald's How the Beatles Destroyed Rock `n' Roll has a title that is much more provocative than honest. Obviously, rock has lasted for nearly four decades since the Beatles disbanded, so the title is clearly misleading. Even if you buy into the idea that the Beatles destroyed a certain type of rock `n' roll (much as someone might argue that Star Wars killed cinema by emphasizing special effects blockbusters over character-driven stories), Wald makes no real argument to back that thesis: the nominal villains do not really even appear until 230 pages into the 254 pages of text. Unfortunately, the deliberately misleading quality of the title is likely to turn readers away from a book that is actually pretty good. It is the subtitle that provides a better description of the book's contents: An Alternative History of American Popular Music. Wald starts his chronicle in the late 1800s, when popular music was much different, not merely by genre but by delivery system. In an era when radios didn't exist and recorded music was in its infancy, the only way to enjoy tunes was through performance. Music generated money either through concert or by selling sheet music for people to perform in the household. In these early days, the emphasis was rarely on the performer: people didn't flock to certain bands but rather to certain music. Eventually, the technology would evolve as well as the economic model for who earned the money from music. And the music itself would change, from rags to jazz and blues to swing and eventually rock. And alongside these musical developments would be social ones: Wald focuses a lot on racial issues and especially a lot on the argument that most popular musical movements were developed primarily by blacks but made commercially successful by whites. Wald's history of music pretty much ends in the days of disco, further eroding the truthfulness of the title. Clearly, however, he knows of what he writes, though he may sometimes get a little too technical for the musical layperson. You may not agree with all of his opinions, but Wald does write a good book that introduces the reader to a more in depth history of music than he or she has probably been exposed to. If only he come up with a better title.

Fresh perspective on popular music; yes, the title is miscast and miscued

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

As nearly all other reviewers have noted, this book spends 230 pages on the history of popular music (jazz, dance music, R & B, rock, pop) before the Beatles show up. Yes, the Beatles and the rest of the British Invasion recast rock into a far more segregated thing that it was before their arrival. While I like the Beatles more than Wald does, I agree with this part of his analysis. Ok, that's out of the way. The real value of Wald's book is in writing a comprehensive history of the American popular music of the 20th century from the point of view of working musicians and ordinary listeners/dancers. We now think of genres such as jazz and orchestral dance music and rock country and so forth as absolutely separate. They once were not quite so separate. Before recordings and before radio, musicians played for people to dance to. Working musicians of all kinds had to be adept at many kinds of music (which basically means many kinds of rhythm to Wald), and they mixed them up to keep dancers going. A popular song was popular no matter who sang it; except for a very tiny group of stars. These days, what we care about is individual performances, individual artists. Radio began to make this change, and records completed it. One of Wald's more interesting points is that our idea of some of the earlier performers is based on their records, which were almost incidental to them and gave a very partial picture of an artist's work. Another is that our picture of the evolution of music is based in large part on the opinions of music writers, many of whom were simply not typical in their tastes. What they liked is not necessarily what most listeners liked. Lots of people liked Paul Whiteman. Lots of people liked Bobby Darin. Lots of people liked a lot of things that rock and jazz critics did not. Shaping music history according to critical tastes is distortion, Wald says. Wald does an excellent job of tracing the changes in how we consume and regard music from the turn of the 20th century to the 70s or so. He paints a clear picture of what working musicians did, and what dancers and listeners did in response. His style is clear and incisive, and he provides plenty of footnotes if you are interested. They don't get in the way of the text. He is a bit repetitious, but the examples are interesting enough that I for one did not mind. There are other, far more ponderous, histories of what recording did to change music. Most of them concentrate on star performers. This one's more interesting than those, because of its emphasis. You can ignore his title and learn from and enjoy his book. I did.

Yeah, yeah, yeah!!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I picked up this book because of the title. I doubted it. Now, to quote one of the bands that followed the Beatles in the dying throes of Rock n' Roll, "I'm a believer." Elijah Wald not only manages to prove his contrary-seeming title assertion, he delivers a splendid history of American popular music and 20th century popular culture. This is not merely the story of folk, jazz, R & B, rock, folk-rock, soul, and the stirrings of disco, hip-hop and rap, it includes the history of race relations and politics through those decades. Wald has delivered a brilliant tour de force. This is without question one of the three best books I have read this year. (See my reviews of Donella Meadows' Thinking in Systems: A Primer and James Workman's Heart of Dryness: How the Last Bushmen Can Help Us Endure the Coming Age of Permanent Drought for the other two). If you love music, you will find much to love in this book. If you care about our enduring legacy of racism, you will find deeper understanding in this book. If you still love the Beatles, you will find yourself saying "Aha!" as you read the concluding chapter. Perhaps the most astonishing lesson herein is Wald's explanation of why music became more and more racially segregated at just the time when society was making strides toward integration, and why the Beatles popularity combined with modern technology separated rock from its roots. This one is a keeper.

Thought-provoking, iconoclastic, debatable

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

"How The Beatles Destroyed Rock'n'Roll: An Alternative History Of American Popular Music" by Elijah Wald ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Author-musician Elijah Wald has written quite a few books, and has a sense of how to pick odd topics, frame them well and make readers pay attention. Hence, the slightly sensationalistic title for what is essentially a rather thoughtful, insightful music history book. This book has a lot to offer, as well as a few aspects that I find debatable and irritating. On the plus side, I like that Wald is standing up for music that members of the pop culture hipoisie consider to be uncool, mainly the Depression-era "sweet band" jazz of artists such as Paul Whiteman. Sweet band is a style that I like a lot. I've written about it on my own music website, and I value its simplicity, catchiness and utter squareness. I like melodic music, and a history that goes back and gives credence to the pure pop music of the 1920s is alright by me. I also like that Wald is willing to take on the received wisdom of the pop music timeline that all rock fans have been taught: that society music and blues begat ragtime, ragtime begat jazz, jazz begat bebop; blues begat R & B, R & B begat rock, etc. etc. As Wald rightly points out, pop culture isn't completely linear and there's a lot of give and take in all directions, and there isn't necessarily an evolutionary progression from point A to points B, C and D. This is all good stuff, especially since the idea of a linear progression from one fad to the other so easily lends itself to the idea that one kind of music is "better" or "more important" than another. Where I have problems with Wald's work is the degree to which he himself remains mired in the same pop-history mythology that he so boldly confronts. Wald readily admits his own cultural and personal biases, clearly stating how he is a product of his own times, a white American kid who came culturally aware in the early 1960s, whose own touchstones were the echoes of the first wave of rock'n'roll, including the wild, energetic bursts of the first few Beatles albums. Like many people of that time, he viewed rock music as revolutionary and cathartic, and invested a big chunk of his psyche in determining what was cool and authentic, etc. While he is honest in laying out his personal frame of reference, he doesn't entirely transcend it. Specifically, Wald is still very much tethered to the whole black-white dichotomy that shrouds the minds of music fans of the 1950s,'60s and '70s (and subsequent decades). In this particular cosmology, the dogma is that "black" music (music made by African Americans) is more vital and authentic than that of whites, and that white musicians are, by genetic definition, more effete and tend to be mere imitators (and appropriators) of the innovations of black music. There is truth to this, of course, but it is hardly an absolute truth, and it sells both whites and b