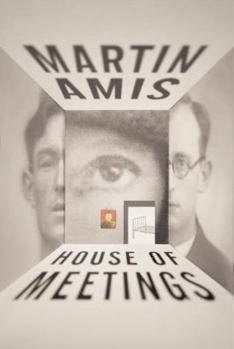

House of Meetings

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

NATIONAL BESTSELLER - An extraordinary, harrowing, endlessly surprising novel set in 1946, starring two brothers and a Jewish girl who fall into alignment in pogrom-poised Moscow--from "one of the... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1400044553

ISBN13:9781400044559

Release Date:January 2007

Publisher:Alfred A. Knopf

Length:241 Pages

Weight:1.00 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.7" x 8.6"

Related Subjects

Contemporary Fiction Genre Fiction Historical Literary Literature & Fiction World LiteratureCustomer Reviews

4 ratings

perhaps his finest work of fiction

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

For years I've been ambivalent about Martin Amis. He is even better than his father at depicting physical and moral decrepitude, and just as talented a humorist. For these and other reasons, I love his previous fiction. However: (1) almost invariably around 4/5ths of the way into his novels he fails to resolve the narrative tension in a convincing or readable manner, and (tied to the first one), (2) when the moral concerns of the author intrude (usually when the novels are being resolved) there is no longer sufficient distance between author and narrator, leading the books to become either muddled or unconvincing. [note: If you are a believer in the anxiety of influence, then there is a compelling explanation for this. Martin Amis is one of the few people that reads his father correctly as being one of the truly great moralists in the Western literary tradition,-and here I refer only to his Kingsley Amis' fiction.] Thus, for years Martin Amis been one of my favorite authors. However, I couldn't point to one of his books and say that it was on my list of favorite books. "House of Meetings" should be on anybody's list of favorite books. I could go on like all of the reviewers and talk up its historical and moral virtues. This worries me though, because lots of books have great historical virtues (e.g. Colleen McCullough's excellent series on the fall of the Roman Republic) without being truly magnificent novels. And Amis' description of Russia is fantastic. . . However, independent of the history, "House of Meetings" is one of the most psychologically and ethically astute novels I've ever read. That is, if Soviet Communism had never happened, and Amis' book was a work of pure counterfactual history, it would still be in the top tier of novels. The narrator's old age reflections on his often morally repugnant life, the narrator's advice to his daughter (reflecting the awful wisdom he has gained from said life), the narrator's presentation of his brother and brother's wife (and the narrator's brother's letter), the narrator's description of the different kinds of prisoners, the narrator's thoughts on what is happening in Russia today. . . not one sentence of it rings psychologically false. Moreover, it's all interesting; both the world presented and the writing style make it an impossible book to put down. Now for the moral aspect of the novel. Yes, communism was horrible, and people need to understand it. However, Martin Amis' non-fiction book on Stalin helped in that task. This novel does that but much more. Bertrand Russell said the main task of philosophy now is to help people to learn to live in a world without certainty without themselves being paralyzed. I think moral literature helps us learn to live in a world of such massive injustice, cruelty, and ignorance without succumbing to it ourselves. Somehow, in creating a fictional world around real monstrous injustices and cruelties, Amis has succeeded in this as we

Blood On The Ice

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

I've been a big fan of Martin Amis' work since I discovered "Money", which forced me to devour all his previous and subsequent books. And I have read with dread fascination a lot of the history of the Soviet Union, including many of the books used by Amis to prepare "House of Meetings" and the great earlier historical essay Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million Amis is a natural with the English language; it's like watching Steve Young throw touchdowns. His earlier, darkly comic novels were a lot of nasty fun, but he went through something of a slump in the last decade. It seemed he was searching for larger tragic themes for his fiction. He may have found them. I think "House of Meetings" is his best book since "London Fields" and may just be his finest book yet. It's like one of those massive Russian novels compacted into a brisk 240 pages; imagine Dostoevsky crossed with Nabokov. In "House of Meetings" he is able to combine a harrowing historical novel about Soviet Russia and serve his own preoccupations with black comedy, human destructiveness, and tragedy. It's a novel about the cruelties of ideology and the annihilating power of twisted sexual obsession. This is a very rare novel by a major Western writer about the Gulag; perhaps it will begin to correct the increasingly embarrassing absence of attention this subject has gotten from Western literary intellectuals. The basic triangular situation of the characters is a familiar Amis situation, but one he has adapted to the tortured history of the times. The nameless narrator is a vital barbarian who grows more sensitive and intelligent with the more and more torment Amis puts him through (although not sensitive enough perhaps to save him in the end.) His brother Lev is not so handsome or assured. He is in fact very passive and inadequate, but because he is a poet he manages to wed Zoya. She is one of Amis' earthly goddesses who becomes the catalyst for the brothers' destruction. During World War II the narrator "rapes his way across eastern Germany" in the Red Army. (That Amis is able to keep us involved with such a morally compromised character is a measure of his great talent.) After the war the brothers end up in Norlag, near the Arctic Circle, "sold into slavery" in the huge concentration camps of Siberia. Amis presents a horrifying but compelling and convincing portrait of those times and places, layered with actual events gleaned from the best histories (like Solzhenitsyn, and Anne Applebaum's definitive Gulag : A History.) After ten years the brothers are set free but discover that freedom is not granted, but struggled after with hideous cost. The epigraph of this novel could be from Shakespeare: "There's a destiny which shapes our ends, rough-hew them as we will." Amis' narrator comes to believe there is a damnation set aside for each of us. But we come to see how unreliable he is. There is an assignation in the so-called "house of meetings" in the ca

A Gulag survivor mourns his lost country and his lost soul

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Martin Amis's new novel is House of Meetings. Obviously making use of some of the research associated with his previous non-fiction book, Koba the Dread, which was about Stalin (though he also acknowledges his debt to some later books than his own) he has written a novel about a "survivor" of the Gulag. But of course the novel is in great part about the ways in which this man didn't really survive the Gulag. The narrator is a Russian born in 1919. He is telling his story, in what seems to be a long letter, to his stepdaughter, an American girl, sometime in 2004 or so. In the present he is taking a trip back to the location of the slave labor camp in which he spent ten years from about 1946 to 1956. He is also agonizing about the botched hostage situation in North Ossetia, ongooing as he writes. It becomes clear he intends to die soon, and this narrative is a confessional, as well as a lament for his native country. The fulcrum of the story is a love triangle, involving the narrator, his ten years younger brother Lev, and a beautiful young Jewish girl named Zoya. Just after the War (in which the narrator, in his words, raped his way across East Germany -- in company, to be sure, with the rest of the Russian Army), Zoya moved into their neighborhood in Moscow, and immediately established a reputation as a woman of little character. But a very beautiful woman. The narrator, a war hero of sorts, handsome, used to having his way with women, becomes obsessed with her, but is rejected. And ends up being sent away to a labor camp. And he is astonished to learn that his rather ugly younger brother has taken up with Zoya, and indeed married her. But then Lev too is sent to the camps -- the same camp. And the two men spend several years there -- though Lev is a pacifist, and refuses to become involved in fights against the camp bullies, or the administrators. Which leads to something of a rift between the two men -- a rift exacerbated in the narrator's mind by his jealousy. But something changes horrendously when Zoya is allowed to make a conjugal visit -- in the "House of Meetings". And when soon after that, the camp is closed and the inmates freed. The later life of the three is also described. The narrator is fairly successful, in Russian terms, eventually emigrating to the U.S., while Lev's marriage disintegrates, and he marries another woman, and has a son, destined to die in Afghanistan. But all is leading to a final confrontation between the narrator and Zoya, and to a final revelation in a long buried letter from Lev to the narrator. All this incident is skillfully unfolded, if to be honest the final letter isn't quite the explosion we have been led to expect. Much of the interest in the novel is in the quite compelling descriptions of life in the labor camp. Besides being a portrayal of slave camp life, and a portrayal of a ruined man, it is to some extent a pained depiction of a dying country. It is very well written. A bit less "bravura" in p

The Brothers Amis.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

British novelist Martin Amis (Money, London Fields, Yellow Dog) is preoccupied with the mass suffering of the Soviet gulags (Koba the Dread: Laughter and the Twenty Million). His latest novel, HOUSE OF MEETINGS, tells the haunting story of an unnamed former inmate of Stalin's labor camps, born in 1919 and now in his 80s who, much like the vile narrator in Philip Roth's latest novel, EVERYMAN, is in "a terminal panic" about his life (p. 144). He attempts to come to terms with his brutish life by explaining in a letter (a 242-page e-mail) to his beloved American "stepdaughter" Venus why he could never open up (p. 3). His letter becomes a compelling meditation on the atrocities of "the Soviet experiment." A World War II veteran of an "army of rapists" now living as an American exile, Amis's narrator and protagonist admits that in the first three months of 1945, he raped his way across what would soon be East Germany (p. 35) before being incarcerated for political transgressions in an Arctic Soviet gulag (Norlag) with his younger, half-brother Lev, a poet and a pacifist, from 1948 through 1956. Lev's only offense was "praising America," the brothers' nickname for Zoya, the beautiful, free-spirited, Jewish-Russian girl they both loved and the woman Lev married before his arrest. (The book's title refers to a camp building in which Lev is permitted a conjugal visit with Zoya in 1956, a visit which cures him of his stutter.) By the end of the novel, HOUSE OF MEETINGS is not so much a romantic triangle love story (as the narrator believes) as a fraternal love story about the consequences of survival. Carefully researched, Amis has written HOUSE OF MEETINGS with the pen of Russia's greatest historical novelists, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, with the wit and dark humor of Nabokov, and with a voice that is unmistakably his own. Highly recommended. G. Merritt