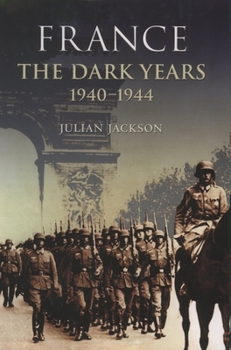

France the Dark Years 1940-1944

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

This is the first comprehensive study of the German occupation of France between 1940 and 1944. The author examines the nature and extent of collaboration and resistance, different experiences of Occupation, the persecution of the Jews, intellectual and cultural life under Occupation, and the purge trials that followed. He concludes by tracing the legacy and memory of the Occupation since 1945. Taking in ordinary peoples' experiences, this volume...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0199254575

ISBN13:9780199254576

Release Date:March 2003

Publisher:Oxford University Press, USA

Length:688 Pages

Weight:0.65 lbs.

Dimensions:1.5" x 6.2" x 9.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Embracing Contradictions and Complexity to Construct a Usable Memory for the Future

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

`The history of France in this period cannot be understood in separate compartments like `the Vichy regime,' `the Resistance', or `collaboration': these existed in dynamic relation to each other, and the history of France in this period must be conceived as a whole. These are strands but they make up one history.' `Vichy contained modernizers as well as conservatives... reinserted Vichy into a longer historical context, drawing out continuities with France's past and future. The future of the history of the Resistance needs to embrace its full diversity - Gaullist and non-Gaullist, Communist and non-Communist, North and South, men and women, French and immigrants - but also to reconnect the history of the Resistance to the society around it, to the French past, and to the Vichy regime.' The social ideology of the governing elite after the fall of France owed its pedigree to the crisis of confidence in parliamentary Republic during the 1930s. `Maurras's movement, Action francaise synthesized royalism, nationalism, and Catholicism into a single doctrine which he called "integral nationalism".' `Nonconformists of the 1930s' whose disillusion with the Republic went deeper,' and their `Order Nouveau' repudiated liberal capitalism as `incapable of developing a rationally organized society.' The political paralysis after the Great Depression (the 1932 elections and their seventeen ministries in eighteen months; radical governments and their efforts to rally conservative support for socialist policies.) opened the way for `direct action by social groups,' where the `illustration of political polarization was less the violence of the extremes than the blurring of the boundaries between the parliamentary right, and the extreme right.' The massive majority that empowered Daladier to revise the constitution `revealed an erosion of faith in the institutions of the Republic across the entire political spectrum.' Vichy was `a testimony to the long-term corrosive effect of Action francaise on French liberalism: all strands of French conservatism were present at Vichy.' Its National Revolution `defined itself first and foremost in opposition to liberal individualism which uprooted people from the `natural' communities of family, workplace, and region.' In its measures against foreigners, like the repeal of the 1939 Marchandeau decree prohibiting the publication of material inciting racial hatred, `Vichy was only extending legislation which had been started under the Republic.' Nonetheless, the National Revolution took a back seat to economic realities (e.g. married women became liable for labor service in Germany, regional constitution reinforcing state control rather than returning to `natural communities.') `The regime, or organizations which developed with its benediction, had up to a point, enjoyed many intellectuals' support, is testimony to the crisis of traditional republican values in France at the end of the 1930s. All these people had shared

Brilliant

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

By all accounts, this is the penultimate history of "the dark years" in France during 1940-44. I agree wholeheartedly. The approach is at once scholarly without being pedantic. Every page is a gem. I have learned so much about not only the years of the occupation, but also about France itself, and why its history (political and social) contributed greatly to the rise of the Vichy government. There are, according to Jackson, proved beyond the shadow of a doubt, many,many strands of influence upon not only Vichy but the Resistance and how both were viewed during and after the war. To those who complain that it is "geared toward specialists", I suggest that you choose your topics a bit more carefully if you want something a bit more simplistic. The subject is not easy, but Jackson does a masterful job of keeping the prose interesting and vibrant. This would get SIX stars if it were possible. Bravo. A tour de force that belongs in every historian's library.

Limited in scope, but excellent in detail

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Buy this book - truly outstanding. I look forward to the other parts in Jackson's three-part series, "France: The Dark Years: before 1940" and "France: The Dark Years: after 1944". I gather there is a special book being brought out called "France: The Very Dark and Frankly Bloody Annoying Months, October 2002 - March 2003"

Definitive World War II History on Nazi-Occupied France

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Julian Jackson's history is the most distinguished account I've read on France during the period from 1940 through 1944. He makes an excellent case noting how the Vichy Regime was indeed part of a longstanding political tradition in France which went as far back as the Ancien Regime; he makes a similar observation of the Resistance, noting how its political philosophy could be traced directly back to the French Revolution. Jackson clearly notes the intense dislike - if not outright hatred - of many French towards their German occupiers, noting that such sentiments may have played a decisive part in ensuring the survival of more French Jews than their counterparts in other Nazi-occupied countries. Much to my surprise, he clearly demonstrates how support for the Vichy Regime came not only from a staunchly conservative elements - but also liberal, and indeed socialist elements - within French society. He also succeeds in noting how figures such as French resistance leader Jean Moulin and future French president Francois Mitterand underwent transformations - some major, but also minor - in their politics, eventually shifting their support from the Vichy regime to DeGaulle's Free French movement. Despite Vichy's reputation for cultural as well as political repression, Jackson shows that cultural activities ranging from the fine arts through film not only survived, but also flourished, at least during the early history of the Vichy Regime.

When Decency pierced the Darkness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Thirty years ago Robert Paxton publishes his classic book on Vichy France which demonstrated both the vigor the Petain/Laval regime sought collaboration as well as the political failure and moral horror of their policies. At the same time Paxton also demonstrated both the widespread support Petain could count on, at least at the beginning, as well as the fact that the regime was not consistently reactionary but also had modernizing elements which the Fourth and Fifth Republics would build upon. Now Julian Jackson has provided his account of the dark years. What has he done to modify Paxton's account?Like Jackson's two previous books on 1930s France, The Dark Years is based largely on secondary literature and memoir literature. Notwithstanding that Jackson's account is unusually thorough. He starts off with a discussion of the interwar years, which looks over such ingredients of Vichy as pacifism, the German threat, Action Francaise, the shock of the first world war and the Depression. He then discusses the Vichy regime, then goes on to discuss popular opinion about the occupation. There is then a large section on the Resistance, followed by one on the Liberation and the postwar Remembrance of the Occupation.Ever since Paxton's book appeared people have commented on how the French have been unwilling to confront the shame of Vichy. Jackson's response to this is a breath of fresh air: "The problem with such comments is not only the unwarranted condescension which underlies them--the assumption that `we', the British, would have faced up to things much better in similar circumstances--but also the fact that they are so patently false....Far from being years which French historians avoid, the Vichy period is probably at present the most intensively researched in French history..." Jackson also points out that the historiography of Vichy was not subsumed in euphemistic darkness before Paxton came along. More important is the emphasis on a fact that Paxton did not sufficiently emphasize. The Germans were never popular under the occupation. The Germans' own reports on public opinion were consistently pessimistic. As one German professor noted in June 1941 "The French rejoice at the fact that British planes are attacking their cities..." The National Revolution under Vichy has some support, and there were powerful quasi-fascist movements in France before the war began, but its popularity too was limited. Petain, by contrast, was popular, at the beginning, though often this was because many people incorrectly believed he was a double game against the Germans (he was not). The fact that Petain did not have a reputation as a Monarchist led many people to believe he was more liberal than he actually was. The remarkable crowds which greated him a few months before liberation were, as Jackson points out, less an endorsement of him than an opportunity to show French flags after their banning under the occupation. At the same time plans for a