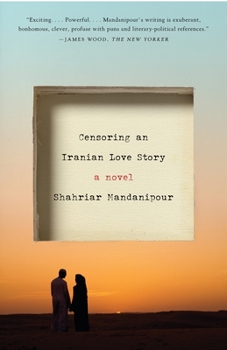

Censoring an Iranian Love Story

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

A NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR - "One of Iran's most important living fiction writers" (The Guardian) shows what it's like to live and love there today. A haunting portrait of life in the Islamic Republic of Iran. --The New York Times In a country where mere proximity between a man and a woman may be the prologue to deadly sin, where illicit passion is punished by imprisonment, or even death, telling that most...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:030739042X

ISBN13:9780307390424

Release Date:June 2010

Publisher:Vintage

Length:304 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 5.2" x 8.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Awesome, endearing, amazing and clever

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Having lived in the Middle-East and worked in a library, blacking out the arms and legs of women in some of the most beautiful art history books.....I can sooooo relate to this book!! So cleverly written and dark humor that stabs you in the heart. I have been to Iran two times and have encountered some amazing generous and hospitable people. I am saddened that they are so suppressed by the regime and therefore depressed but still trying hard to make their life as livable as possible!!! I can't wait for more books to be translated into English by the same author.

So Pleads the Reader . . Read This Right Away!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Lest you read no further than this line, let me say with feeling: read "Censoring an Iranian Love Story." Read it right away! For reasons we know, this country has been ambivalent toward all things Iranian for thirty years. Lately, the streets of Iran have been embroiled with Twitter-driven uprisings while we in the West have looked on in amazement. Aren't these the people that called for the death of the "Great Satan?" Apparently not. "Censoring an Iranian Love Story." is a painfully beautiful book, florid with the author's viable, breathing description of contemporary Iranian life. The author, Shahriar Mandanipour has chosen not to write a love story for the ages, but has instead, written a heartrending story for the moment (eventually, this book will stand as an important history lesson). The "moment" in Iran is harsh yet beautiful, like the lives of Sara and Dara, central characters of the book. As the author reveals his own struggle to rise above the exhaustive, exhausting limitations of state theocracy, readers glimpse (intimately) what precisely has gone wrong with the Revolution and how it threatens the artistic impulse of its citizens. Mr. Mandanipour has managed a difficult feat. He illuminates conditions within a society largely closed to us for 30 years without overt criticism. Which is to say that Iranian reality is infinitely more subtle than we have imagined. The central characters of Sara and Dara are highly sympathetic as intelligent, young adults facing the fierce social restrictions imposed by law. Dara is an ex-film student and ex-political prisoner whose academic records have been expunged, along with his future. Sara is a student of literature with more mettle than those around her suppose. As Mr. Mandanipour explains, the two characters are named after the Iranian counterparts to America's" Dick and Jane" of early reading fame . . . hence they are archetypal. He describes the lives of his young lovers to show what it means to face unrelenting state censorship aimed at regulating social and moral behavior with officious zeal. Often in the book the writer as narrator demonstrates how he filters words and phrases for their indirect meaning . . . with a view to getting his work past the censor, a wringing task. Just as Sara and Dara disguise the appearance of their romance, the author constantly self-censors to avoid the harsher consequence of direct description; imprisonment, professional banishment, or worse. The logistics of pleasing an assigned-for-life-censor or for Sara and Dara, avoiding the Morality Police, are unabashedly Orwellian. Forget what you may already "know" about Iranian society and read "Censoring an Iranian Love Story." Whatever cultural references readers may lack the author graciously explains, often with great charm and humor. "Censoring . . ." has an fairly idiosyncratic style but is more enjoyable for the author's literary device. The author clearly loves his country, his people and their tr

"The good fortune or misfortune of lovers is that they quickly forget their good fortunes or misfort

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

When I picked up this book, written by a popular Iranian author, my only expectation was that it would be an unusual view of the writing life in Iran today. What I never expected was that the book would be so funny! Witty, cleverly constructed, and full of the absurdities that always underlie great satire, this unique metafiction draws in the reader, sits him down in the company of an immensely talented and very charming author, and completely enthralls. Having reached the "threshold of fifty," Mandanipour says he intends to write a love story, and, most importantly, that "I want to publish my love story in my homeland." He then becomes the narrator of two stories---the fictional love story of Sara and Dara, which appears here in boldface, and a metafictional commentary by the author, in regular type. Experimenting with what to include in his love story and what direction to take, the narrator, named "Shariar Mandanipour," writes for the censor, ironically named Porfiry Petrovich, the police investigator in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. "Because I am an experienced writer," he says, "I may be able to write my story in such a way that it survives the blade of censorship." The author is true to his reader, however. Whenever he believes that Petrovich will question something, he either crosses it out himself (leaving it visible so that the reader can read, literally, between the lines), or he changes direction and rewrites the action of the story. He never rants or gets angry, preferring instead to show the excisions as silly. He understands that an Iranian audience has far different cultural expectations from a global audience. In the love story, Dara has worshiped Sara from afar for a year, having seen her briefly at a student demonstration, and he leaves her coded messages hidden in library books. She never sees him, however. Gradually, the two young people begin to have "whispering computer chats," and eventually meet secretly in person, avoiding situations in which anyone from the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance will see them. Though they fall deeply in love, Sara is also being courted by Sinbad, a very wealthy older man, and her family knows that if she marries him, they will all be much better off. As the story progresses, the author comments about censorship in his own life, from the naming of his children, to his defense of scenes in his novels and stories. After one hilarious meeting with the censor, he tells his publisher that "Mr. Petrovich forgave us three breasts and two thighs." Though the Iranian Constitution allows free speech, it does not say that books and publications can "freely leave the print shop." Hence, many books get printed and then never released, unable to get a permit. Throughout the novel, the author maintains an easy-going, conversational style and a wry, self-deprecating sense of humor. A dead midget hunchback becomes an ominous, repeating symbol, and when Dara is followed and

Behind the curtain(s)

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I was sold when I saw that the jacket bore recommendations from Rabih Alameddine, author of The Hakawati (a great recent novel with a quite different story-within-a-story concept), and Diane Abu Jaber, also a great novelist who tackles cross-cultural issues. Another comparison I might make is to The Black Book, by Orhan Pamuk--though this is less gloomy and more personal of a story. The narrator-author and his nemesis Porfiry are the real entertainment here, although the characters within the author's self-censored novel get more spunky as the story progresses. The relationship of the author and censor reminded me of another great minder-citizen relationship, the one in Gunther Grass' "Too Far Afield" (Grass' novel is much more work to read, though). I was surprised by the creative twists in the second half of this novel--I generally avoid magic realism stuff--but these wackier elements of this story are well under the control of the author and do serve to bring forth the author/narrator's struggles as a writer--it does not devolve into silliness. If you like it, try tackling Alameddine, Pamuk and Grass afterwards....

excellent

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

As Shahriar turns fifty, he is tired of his futile attempts at writing a strong novel only to have the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance censor the guts of each one. It is so bad he knows exactly what Pofiry Petrovich, as he calls his official hound, will find objectionable, which usually guts the story line. Shahriar decides to try an upbeat optimistic tale, a love story set in modern day Iran. He begins writing how Sara and Dara meet at the library and fell in love. However, Iranian Campaign Against Social Corruption forbids this couple being alone [...]. This translation will be considered one of the top satires of the year as Shahriar Mandipout uses censorship to tell a story of romance in modern day Iran, but could be in almost any place as for instance the political corporate media complex assaults those with an opposing view. The story line is super as Shahriar the fictional author edits his work by crossing out what he expects deleted, which guts his writing. Fans will relish this excellent use of romance to lampoon censorship. Harriet Klausner