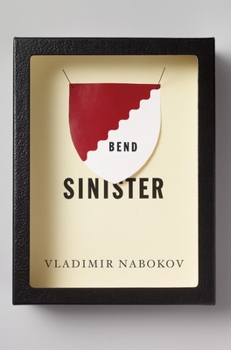

Bend Sinister

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

The first novel Nabokov wrote while living in America and the most overtly political novel he ever wrote, Bend Sinister is a modern classic. While it is filled with veiled puns and characteristically delightful wordplay, it is, first and foremost, a haunting and compelling narrative about a civilized man caught in the tyranny of a police state. Professor Adam Krug, the country's foremost philosopher, offers the only hope of resistance...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0679727272

ISBN13:9780679727279

Release Date:April 1990

Publisher:Vintage

Length:272 Pages

Weight:0.55 lbs.

Dimensions:0.6" x 5.2" x 8.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Just READ THIS

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Of the five books I've read by Nabokov, this is my favorite. I'll spare mentioning that being one of his first America-written, English books, he masters the English language. (Oops. I mentioned it.) As often as people credit him for his inventiveness in his stylistic methods (which is at full experimentation here) you just don't hear enough about his amazing imagination. This book is set in a fictional European country, which is what initially fascinated me. It's quick, funny, sad, nostalgic, and haunting. People always use that word: `hautning'. But what does that really mean? In the case of this book, from beginning to end, we're introduced to a dream. I've read plenty of book descriptions in which people say a book is `haunting' or `dreamlike' in order to convey its surrealism, but this book is a perfect example. The end of the book, without giving too much away, is terrible (in the sense that it's sad/horrifying/abrupt) but in a good way. The book is short, and honestly feels as though it IS trying to convey the feel of an epic dream that goes on all night, only to go from slightly dreary to overwhelmingly awful, and in such a short book, this nightmare manages to progress wonderfully. By the time I finished the last page, I honestly felt like I had awaken from a terrible nightmare. This book is good on many levels. Not only do you have an interesting storyline, but Nabokov never hesitates to free himself with only the best prose experiments and shifts in narrative that I've ever read. While other authors tagged as `post-modern' barrage us with stream-of-consciousness or switching narrators, falling short of even telling a story right, Nabokov uses methods that not only delight us with their originality, but help the story move along better. A good deal of the story is told in third person, but we have occasional lapses...one chapter is told in first person as a memory piece, speaking TO his dead wife. Absolutely beautiful. Another chapter is told in a strange, present tense walk through of events with bits of philosophical dissection thrown in the midst, as though the main character is splicing the narrative up with one of his essays. Even the third-person portions are just pure poetry. It's like a poem disguised as a novel. Read this book now. The only CON I have is that the author is dead.

Mediocrity is a cruel tyrant.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Bend Sinister is a story about the rise of the party of the average man and the struggle of the country's foremost philosopher, professor Adam Krug, against the totalitarian regime that comes to power and its leader Paduk. Though one of the most dreadful stories imaginable, Bend Sinister is told masterfully, complete with brilliant descriptions that give the reader everything needed to engage the imagination and make a far-off, vaguely Eastern European country come to life. Always helped to understand Krug's frame of reference, the reader is given description after description of small, everyday things that might remind the protagonist of the kidney that failed in his wife and led to her death at the beginning of the novel. Like the horrific story Nineteen Eighty-Four, the protagonist ultimately succumbs to the totalitarian regime. For my tastes, perhaps typical of the American optimist view, I prefer to see the protagonist ultimately succeed in the face of tyranny. (Ayn Rand, who like Nabokov, fled Soviet Russia and landed in the United States, which was designed specifically to prevent the rise of a tyrant, wrote many stories of the individual vs. totalitarianism.) That said, Nabokov chooses not to show the success of the individual but the failure of a dictator his regime to get the one thing that it prizes not because of the individual's strength but because of the regime's own ineptitude. The novel is both brilliant and deeply disturbing. In its conclusion, the reader finds the author finishing the novel, in a wonderful (and welcome) device that helps the reader to make an easier transition from the intensity and emotion of the story that concludes with the insanity of the protagonist back to the reader's own real world, where one would hope that such dreadful stories are only found in works of fiction. Bend Sinister is widely regarded as the most political of Nabokov's work but I think it correct to consider the book not a political novel but a philosophical one. Perhaps by the time one moves to the real of public policy there can be no real difference between philosophy and politics but Bend Sinister shows a world view clearly -- where a totalitarian regime, no matter how well-intended, no matter how noble its goals are assumed to be, can succeed. This world view, interestingly enough, is not only widely held in literature but also has some basis in history worthy of consideration. Benjamin Franklin, in "the Pit" in London is an example that readily springs to mind. Up until being charged with every bit of nonsense that could be conjured by his enemies in England, the famous and highly-influential "Doctor" Franklin was one of the Crown's best defenders and loyal subjects in the American colonies. If we may safely believe the account offered by our own historians such as H.W. Brands, it is this idiotic and petty act that sets Franklin against Parliament and aligned with the separatists who would become the Founding Fathers of the most p

Nabokov's most political novel, by turns funny and tragic

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

Bend Sinister (1947) was the first novel Vladimir Nabokov wrote in the United States, and his second novel in English. Like one of his later Russian-language novels, Invitation to a Beheading, it is explicitly political, in a way generally foreign to Nabokov. (Indeed, to write a "political" novel was rather against Nabokov's usual artistic philosophy, and in his 1963 Introduction to this novel, he takes pains to point out that the focus of the novel is the main character's relationship with his son, not the repressive political conditions which drive the novel's plot.) Bend Sinister opens with the death of Olga Krug, beloved wife of philosopher Adam Krug. Krug is left with an 8-year old boy, David, in a country torn by a revolution led by an oafish schoolmate of Krug's, Paduk, called the Toad by his fellows at school. The new regime attempts to gain Krug's support, offering both the carrot of a University presidentship and the stick of veiled threats conveyed by the arrest, over time, of many of Krug's friends. The brutal climax comes when the new regime, almost by accident, realizes that the only lever that will work on Krug is threats to his son, then, due, apparently, to grotesque incompetence, manages to fumble away that lever.The novel is (one is tempted to say "of course") beautifully written. Passage after passage is lushly quotable, featuring VN's elegant long sentences, lovely imagery, and complexly constructed metaphors; as well as his love of puns, repeated symbols, and humour. The characters are well-portrayed also -- Krug, of course, and his friends such as Ember and Maximov, as well as villains such as the Widmerpoolish dictator Paduk and the sluttish maid Mariette. The novel, though ultimately quite tragic, is filled with comic scenes, such as the arrest of Ember, and comic set-pieces, such as the refugee hiding in a broken elevator. As VN asserts, the relationship between Adam Krug and his son is the fulcrum on which the novel turns, and it is from that the novel gains its emotional power. But much of the novel is taken up with rather broad satire of totalitarian communism. The version portrayed here is of course an exaggeration of the true horror that so affected Nabokov's life, but it still has bite. The central philosophy of the new regime is not Marxism per se, but something called "Ekwilism", which resembles the philosophy satirized in Kurt Vonnegut's short story "Harrison Bergeron" -- it is the duty of every citizen to be equal to every other, and thus great achievement is unworthy. (It is not to be missed that Paduk was a failure and a pariah at school.) All this is bitterly funny, but almost unfortunate, in that it is so over the top in places that it can be rejected as unfair to the Soviet system which it seems clearly aimed at. That's really beside the point, however -- taken for itself, Bend Sinister is beautifully written, often very funny, and ultimately wrenching and tragic.

Stop plucking your nose hairs and read this book

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

"Bend Sinister" is one of Nabokov's supreme masterpieces and like all great works of art it operates on many levels simultaneously. Not the least of these levels is that of the `black comedy,' one of the most savage and sophisticated ever written. Krug is a world famous philosopher who in his youth was schooled alongside an annoying lad named Paduk whom he used to, almost felt compelled to, bully. Through some grotesque trick of fate Paduk has become dictator---of the whole country that is--- and most of the citizens are busy worshipping his calls to `duty.' Krug's wife has just died and he is deeply attached to his 8 year old son David. Paduk and his cronies are trying to get Krug to endorse the new regime--put his prestige behind it and give it more legitimacy. Krug's friends try to warn him to leave the god-forsaken country while he's still able, but he's a conceited and stubborn bastard with way too much faith in his own powers and the `goodness' of humanity. So he acts the wise-guy, sticks around and gets gradually pulled into a nightmare he can't wake up from. By creating the Twilight-Zone-like imaginary land of Padukgrad, Nabokov frees himself from any specific locale and is able to incorporate multiple totalitarian state caricatures of the German, Italian and Russian variety all at once. Bits and pieces of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin all collide and overlap in the Paduk character. Nabakov goes into flashback, and dream and `thinking' states quite often without warning, and without clearly indicating where one state ends and the other begins. It all flows together like reality. This is good because it forces readers to constantly stay on the alert or be baffled. He sets traps for superficial readers left and right and really doesn't want them reading his novel.Through Krug's ruminations, Nabokov makes some of his most poetic observations about philosophical questions of life and death and existence.The recurring motif of the oblong puddle emphasizes the connection between Nabokov's layer of life where it also occurs (revealed in the spectacular ending) and that of his fictional creation Krug. Unlike the willfully ignorant leftist intellectuals of the West who were at the time busy worshiping Stalin, Nabokov in 1945 was fully aware of what was going on in the land of his birth and how it was going on. Nadezda Mandelstam's famous book about the Stalin era persecution of her husband, the poet Osip Mandelstam, "Hope Against Hope," which came out some 25 years later corroborates to a startlingly accurate degree many of the things Nabokov describes in his `fantasy' creation.Bits of Lenin's speeches make appearances here and there. In Chapter 13 Nabokov uses sections of the Soviet constitution, full of non-sequiturs and idiotic declarations of `obvious fact with no further proof required' (which uninitiated readers will think are too absurd to be true), to emphasize just how absurd the `real' world can often be and how much s

Slapstick and sadism - nauseating brilliance

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 25 years ago

Gobsmacked. Speechless. I don't know what to say about this book. I finished reading it last night, and am still reeling in disgust. Bend Sinister is one of the few novels in which you can tangibly feel pain.Ostensibly a dystopian fantasy, the novel couldn't be further from a well-meaning but cold-hopping diatribe like 1984. The problem with Orwell's novel, besides its naive sexual politics, is that its mode is as totalitarian as the events it describes. The 'reality' (i.e. its form, not contents) of the world of the book is total and unquestioned, as are Winston's responses. The reader must submit completely to the illusion. We are either on Winston/Orwell's side, or we are fascists.Bend Sinister is 1984's polar opposite, profoundly distrustful of reality and illusion. Like 1984, the events take place through a single protagonist, Adam Krug, but this viewpoint is never textually stable: constantly ironised, undermined, splintered by other viewpoints, other texts, by the author himself. The tone veers wildly between subjective contemplation, cool pastiche, terrifying farce and unspeakable horrors. Like all Nabokov's works, the most sublime linguistic, figurative and formal beauty is utilised to relate the ugliest terror and pain (I'm not sure about the novel's misogyny, though). This textual unrest is appropriate to a world in which all norms and values are thrown out of kilter, and stamped on by jack-boots. Passages of delicate Proustian lyricism asset the primacy of the individual consciousness and aesthetic sense over the tyrannies that attempt to crush them; but if this consciousness cannot defeat tyranny, it can only go mad.