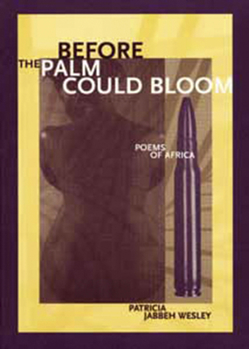

Before the Palm Could Bloom: Poems of Africa

In Before the Palm Could Bloom, Patricia Jabbeh Wesley writes poems of the Liberian civil war and of the devastation it has wrought: 2000,000 dead including 50,000 children and 750,000 citizens forced... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0932826644

ISBN13:9780932826640

Release Date:November 1998

Publisher:New Issues Poetry and Prose

Length:86 Pages

Weight:0.50 lbs.

Dimensions:0.3" x 6.1" x 8.5"

Customer Reviews

2 ratings

a beautiful and powerful collection of poems

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Patricia Jabbeh Wesley was born in Tugbakeh, Liberia. She and her family moved to the USA in 1991, during the early years of Liberia's civil war. In Before the Palm Could Bloom, Wesley writes vividly of those war years, of life in the time before, and of a future full of both uncertainty and hope. Wesley's picturesque poems of village life-and particularly her description of village life (before and after the war) in Tugbakeh: A Song-illustrate how much we have lost because of the chaos in our country. Child Soldier, one of the most powerful poems in the collection-and the one from which the book's title comes-is a moving piece about real children who played chilling roles in the destruction that ultimately left over 200,000 dead. Throughout her book, Wesley writes with the authority and sensitivity of a survivor who is already thinking about the healing that must follow the violence. But not all her poems are full of sorrow and longing. They Say and Monrovia Women are timeless and humorous poems of Liberian women's experiences and perceived behavior. Some, like Big Ma, pay tribute to people Wesley knew. Still others uplift the spirit with plans for repatriation of Liberians from the diaspora. In the upbeat poem One of These Days, Wesley describes the great rejoicing that will take place when all the refugees return to their homeland. Homecoming, one of the last poems, is a bit more poignant in its plea: I don't want to be a stranger / when I come home. / Yes, I'm a wanderer, / a woman. / But I don't want to be a stranger / in my hometown. Before the Palm Could Bloom is a beautiful collection of poems that, together, presents a complex Liberia-a part we may never know again, a part we never want to relive, and much that we yearn to recreate for future generations.

Poems of Liberia's war

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 22 years ago

In Wesley?s poem "Outside Child," a man hands his wife a child wrapped in a blanket; the child is his, he says, and the wife is angry. "Where is this child?s mother?" she asks. This Liberian woman has been a dutiful wife, and she has cared for her own children, and this product of her husband?s philandering should not be her concern. But even as she is furious at the man, the "outside" child at her breast has won her over. She will care for this baby, "This thing that will rob her of heart and mind."So seemed Patricia Jabbeh Wesley?s poetry at first glance: poems from outside my world. There are enough African words peppering these poems to merit a glossary at the back of the book. What is this place in Africa to me? I wondered as I began to read. What is this war to me???it is so far away. But as soon as I looked into the faces of these poems, I cared desperately, and I knew that this war, like all wars, belongs to all of us. Though I am from Wesley?s adopted Michigan, land of maples and hickories and cedars, I hold to my breast these poems of the fertile land where kola nut trees and breadfruit trees and palms grow.As the husband stands before the wife, awaiting the verdict, weeping, she sees him as "a tree after lightning has struck." Throughout this book borne of war-torn Liberia, we read of trees and people felled and uprooted, trees and women offering fruit and crops, trees taking over cities. Children should be running into the woods to play and harvest the fruits, but instead we children march off to war. The Liberian civil war (1989-1996) was famous for its induction of child soldiers, and Wesley brings us the heartbreak of the mothers of those babes with guns and "adjustable ammunition."The war was unbearable, but the women and men and children who have survived did bear it and continue to bear their losses. There was so much death, according to the poem "War Children," that the ground would no longer accept the dead: There is no burial ground anymoreIn their shallow graves the corpsesdance Liberia?s cradles empty.These poems, however, are not tales of despair. The war-torn landscape is brightened by Wesley?s love of village tradition and her joy in remembering the liveliness of Monrovia, as well as her honesty in depicting the more ordinary, ongoing battles of the male-female domestic situation. If the war will just end, these poems seem to say, we will grieve for a long time, but eventually the land will forgive us, the trees will grow and bloom again: the mango, the banana, the breadfruit, the kola nut, and especially the palm, for then the palm wine can flow for the people of Liberia, and all those who left will come home and be welcomed at the doors of their old homes. They will rejoice, as Wesley describes in the first stanza of "One of These Days:"One of these daysthere will be rejoicingall over the place.There will be so much shouting,so much wailing,so much dancing.There?s going to besuch dancingas we?ve never seen before.There