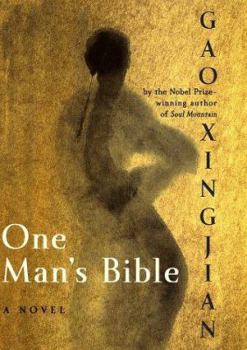

One Man's Bible

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

"Courageous ... One Man's Bible is driven by the sweeping panorama of history and the suffering and reconciliation that underlie it."-- Washington Post Book WorldPublished to impressive critical... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0066211328

ISBN13:9780066211329

Release Date:September 2002

Publisher:Harper

Length:464 Pages

Weight:0.05 lbs.

Dimensions:1.4" x 6.1" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

beautiful, accomplished work

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Gao Xingjian's second novel, "One Man's Bible" contains partially autobiographical life story of a Chinese writer, who tries to find his own place, peace of mind and right to writing and publishing in the Communist China. The writer, living in permanent exile from China, goes to Hong Kong to attend a premiere of one of his theater plays. There, he meets Margarethe, one of the women who had an impact on his life. Margarethe, a German Jew, who stayed in Germant despite many doubts and reservations, is enquiring about the writer's past and this triggers and avalanche of memories. In fact, it is not a novel compositional trick, but because of Gao's dream-like style, similar to "The Soul Mountain", it seems still fresh and original here. The chapters, which describe the Chinese past of the main character during the Cultural Revolution are separated by the ones closer to the present. The difference is stressed by the changes in narration between second and third person. Among enemies and friends, career wolves and people desperately trying to preserve their individuality and self-respect, the young writer tries to figure out his own place, which requires a lot of time and effort, many schemes and being always a step ahead of the others. To write and publish in the capital, one must escape the Party purges, must have a job, a right to lodging in a tiny room in the communal apartment, an impeccable past and a perspective of a career within the Party. Initially, the protagonist manages quite well. He becomes a leader of young rebels in yet another uprising, labeling the former previous party officials as "The Snake Spirits" (name given to all enemies of the system). He is also a lover of one of the Party leader's wife. Thanks to her warning (apparently the proofs of his disloyalty have been found (in the form of the information that in the remote past, just after the war with Japan, his father was in the illegal possession of weapons), the writer finally realizes that he will never be able to find for himself a safe place in the communist structures, allowing him creative freedom. Only then he decides to escape, initially hiding n the far away, mountain village, under the pretenses of rehabilitation through physical labor. After a long period of creative hibernation and waiting, he manages to leave China and stay abroad permanently, getting the status of the political refugee. This seemingly realistic plot is spiked with the descriptions of events from emigrant times, the weird dreams pestering the protagonist and the masterful portraits of people who he met in China (the whole gallery of human types, from small cheaters, through people using their professional positions to the good and bad purpose, to intellectuals broken by the system) and outside (especially interesting are the female characters - already mentioned Margarethe and Sylvie, a person whose personal experience separates her like a chasm from the protagonist; it is interesting to notic

Engrossing

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This is a fantastic autobiographical novel about the author's experiences under Mao's China and how it affected him and others. The subject matter itself is enough to reccomend this book because we rarely get insights into this closed world and must strive to understand it as it emerges as a world economic power. The author uses an interesting techinque of detachment where the main character is also the narrator who speeks most often in the third person. Irme Kertesz in his novel "fatelessness" beautifully dscribes how people can survive even the worst suffering, such as the holocaust, by detachment of soul from body. In "Fatelessness", the protagonist survives the concentration camps by escaping outside himself and comes to not only view his suffering and surroundings in the third person but becomes so detached that the physical pain, wounds, illness and suffering of his own body are described and experienced as a thiid person. This mode of escape was subconcious and persisted after the war, leaving a permanent scar of detachment that leaves the reader wondering how the protagonist will relate in peacetime. Gao has evidently experienced a similar form of coping mechanism that is evident in the sections of the novel that take place in the present, during his expatriat years. It becomes manifest by his casual serial sexual encounters with women who also have similar problems of forming lasting bonds and attachments because of trauma (rape etc). Gao's inability to form a lasting personal bond extends to his lack of attachment to China, his people and his new home, career and friends. Though his insights are [rofound, Gao's emotions and actions are superficial and dream-like. The most brilliant technique is his use of the word "you." The detached narrator (Gao)uses this word to refer to the subject (Gao)as if he is writing for and talking to himself. I have only seen this technique used in Gao's other novel translated into English "Soul Moutain." Later in the novel, when describing the past he uses "him" to describe the subject "Gao" living in Mao's China. The Narrator uses "you" to refer to the Gao in the present, expatriat state. The use of "you" and "him" has a multilevel effect on the text and the reader. "Him" Gao of the past becomes "You" Gao of the present - a different level of detachment. "Him" Gao is the Gao of the present describing the Gao of the past as if from a distance, as if that person no longer exists and is dead or lost. The "You" Gao is more familiar, closer, intimate yet detached, a different, mature Gao of the present who is having these relationships, having his plays performed and struggling with the present novel and his past. If a man is the sum of his experiences we are left still wondering who the real Gao is and if he knows himself. It is as much a discovery of Mao's oppressive China as an effort of self descovery -- both painful. The other effect of the use of "You" used by the narrator to desc

Cultural Drift

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

To this day, the bizarre, cult-like events of the Cultural Revolution remain a prime focal point for Chinese novelists and, especially, memoirists. Writers from Adeline Yen-Mah, Jung Chang, Jan Wong, and Anchee Min to Yu Hua, Mo Yan, Dai Sijie, and Yan Geling have plumbed the depths of political capriciousness, human debasement, and the sheer will to survive in their own lives or in those of their fictional characters. Yet few if any Chinese writers have dared examine the effects of the Cultural Revolution on their later, post-Tiananmen Square massacre (1989) lives. Gao Xingjian's semi-autobiographical novel, ONE MAN'S BIBLE, is the first I have encountered, and the results are hauntingly devastating. The story opens in a Hong Kong hotel in 1996 with the unnamed Chinese narrator (an internationally successful playwright) and his temporary paramour, a white Jewish woman of German descent named Margarethe. Theirs is an affair of mutual convenience and simple animal lust, but it is also a continuation of two largely hopeless searches for human closeness and warmth even as both characters deny that they seek such a thing. Margarethe works insistently to draw out the narrator's past, asking him to tell his life's story and suggesting that he turn it into a book. The narrator for his part insists that such a thing is not possible, that "things in China can not be explained by language alone," yet the book of his life unfolds before us in chapters that alternate (for the first half of the book) between his present-day encounter with Margarethe and his autobiography. What emerges from this approach is a haunting tale of a rational, intelligent man trying desperately to cope with the utter irrationality of the Cultural Revolution. At first a nonpolitical citizen of Beijing, the narrator decides that he can best survive by becoming a faction leader. Having established his revolutionary bona fides, he then lays low and chooses his moves carefully, ultimately realizing that his next move is to the countryside, to keep his head down as a peasant farmer and teacher for perhaps the rest of his life. To maintain his sanity, he secretly writes about his feelings and experiences, keeping his papers well-hidden from nosy neighbors. Over time, he discovers that survival under Mao requires repeated acts of selfishness and disregard for the feelings of others, particularly the women who pass through his life, offering sexual temptation coupled with the threat of personal ruin. Ultimately, Margarethe returns to Europe and disappears from the alternating scenes, leaving Gao to examine ever more intensely his own past, his failings and regrets and lost relationships. He never shares with us the manner in which he "escapes" from China, partly because it doesn't really matter and partly because, in a psychological sense, he will never escape. By using the alternating chapters, the author establishes a clear divide between history and the present while simultaneously i

At least, a Chinese Mark Twain

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Gao's penetrating and honest insights about Chinese people, the Cultural Revolution, and his personal experience and feeling enable him to create a book that is as realistic and beautiful as books created by Mark Twain. It is a great achievement!

Engaging with food for reflection

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

I highly recommend this book. Initially I found it difficult and the sequences with Margarethe were perhaps a little bit tiresome but warming up to the story I got a lot out of it. I don't agree that the horrors of the Cultural Revolution were just like the purges and fascist regimes in other parts of the world. Instead of simple oppression by evil regimes against suffering citizens there was instead millions of little civil wars in every commune, every factory, every office across the country.The style is a little detached at times but this adds to the atmosphere. The writer doesn't try to create victim-heroes but shows what it was like for the compromised majority. A world dominated by fear and compromise, favours furtively delivered and favours frantically called in. Beatings, up-rooting and death are common in a situation where one is not allowed to be neutral, one must take sides to survive. It was corrosive to all human relationships and leaving a generation traumatised. One can only wonder what it really meant to experience it, or what it would be like if social purists or Christian Reconstructionists came to power in ones own country.The description is thorough and uncompromising; the experience of being caught up in the events well communicated but it is neither a confession nor an accusation. It is ultimately the tale of ordinary fearful people put in terrifying circumstances where every thing you ever did or said could betray you. At the end there is a sort of acceptance and personal reconciliation.Read it, its good.