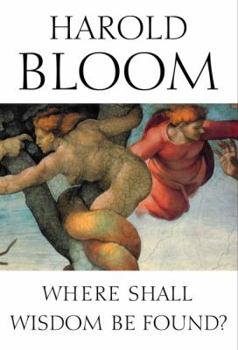

Where Shall Wisdom Be Found?

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Bloom, the renowned literary critic, has launched another masterpiece that poses the age-old question from the Book of Job: Where shall wisdom be found? Arguing that reading itself is a quest for... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1573222844

ISBN13:9781573222846

Release Date:October 2004

Publisher:Riverhead Books

Length:284 Pages

Weight:1.30 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 6.3" x 9.3"

Age Range:18 years and up

Grade Range:Postsecondary and higher

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Wisdom of the great Reader

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Harold Bloom has so far as I know read more of the great Western tradition in Literature than any other person. I am no small reader myself, but beside Bloom my reading, my grasp of what I have read, my retention of what I have read, the connections I make with other works I have read, are small. Bloom is a great Genius of Reading, and in this book he reads Job and Ecclesiastes, Homer and Plato, Cervantes and Shakespeare, Montaigne and Francis Bacon, Samuel Johnson and Goethe, Emerson and Neitzche, Freud and Proust, The Gospel of Thomas, Saint Augustine( on reading). He reads the opposing pairs in his search , for what he regards as a fundamental goal of reading in general, the attainment of Wisdom. Bloom is such a rich mind, so filled with the love of literature, that every page brings new insights and great quotations from classical works. He gives the sense in his writing and reading that the very involvement with these texts is a deep spiritual exercise, an art of self- development and perfection, a probing towards our own better selves. He does this however with a strangely competitive idea, one of his central critical ideas is that of great writers in struggle with their predecessors and contemporaries. In this book the pairs of each chapter are taken as opposing, and involved in an `agon' or struggle for precedence and preeminence. In his chapter on Homer and Plato he repeatedly emphasizes the effort of the Philosopher to displace the Poet. And in his chapter on Shakespeare he even goes so far as to make Shakespeare defeat all Philosophers in his achievement of Wisdom. This `anxiety of influence' and ` agon ` aspect of Bloom I think of as a bit childish, and very American. Shakespeare is `number one' in Bloom's book of life. And Shakespeare and Montaigne in Bloom's conception defeat or stand above all subsequent competitors, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky , Joyce, Proust, etc. But these kinds of comparisons and the pressagentry involved in them are a small part of the great weave of insights Bloom provides. All of the chapters of this work have brilliant insights, but one favorite of mine was Bloom on Montaigne. He cites Montaigne's prescription for being most human," There is nothing so beautiful and legitimate as to play the man well and properly, no knowledge so hard to acquire as to how to live life well and naturally, and the most barbarous of our maladies is to despise our own being". Bloom tells us in this work of his own private crises, the illness which at seventy brought him to greater consideration of his own mortality- the depression he suffered for a year at the age of thirty- five which led him to a year of reading Emerson backwards and forwards. Bloom like another of his great heroes , Samuel Johnson stands as a kind of Ideal Reader in his time. And this when one of Bloom's laments is that the very love of and reading of great Literature has been compromised by an academic world given to rigid misreadings of the great canon,

the realness

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

A typically against-the-current grain tome from Bloom that is both refreshing and an antidote to so much of how literature is treated in academia these days. Having completed a 'Literary Studies' major recently, and retaining my love for literature despite it (thanks to writers like Bloom perhaps...), I would have to say thank God for him (if I wasn't an athiest). Bloom does require some prior knowledge to understand and come to grips with - in particular some experience with being taught literature at a high level. For the benefit of some of the reviewers out there, the comments he makes reagarding 'schools of resentment' etc are backed up by this experience, by the realness of what is happening, as opposed to the usual footnote-the-many-like-minded-academics-I-know methodology in practice. There is a plethora of other titles dealing with culturalism (and every other sort of 'ism') out there that are being rammed down our throats like brick-sixed laxatives, so celebrate this in the name of pluralism at least. If you believe that western thought and art still has validity and power and wisdom contained within it, then this book is well worth examining. If not, there's plenty of other titles out there for you. Plenty.

Reading as a quest for poetic wisdom

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Esteemed literary critic, Harold Bloom (HAMLET, GENIUS, HOW TO READ AND WHY, SHAKESPEARE: THE INVENTION OF THE HUMAN, THE WESTERN CANON, THE BOOK OF J), is also a Professor of Humanities at Yale University and a former professor at Harvard. In his latest book, WHERE SHALL WISDOM BE FOUND? (the title of which he has derived from Job), Professor Bloom leads us on an enthusiastic pilgrimage through the Western canon to the "Canterbury" of poetic wisdom that can be found in reading Job, Ecclesiastes, Plato, Homer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Montaigne, Francis Bacon, Johnson, Goethe, Emerson, Nietzsche, Freud, Proust, the Gospel of Thomas and St. Augustine. "Of wisdom," Bloom writes, "we cannot embody it, yet we can be taught how to know [it]" (p. 284). And Professor Bloom--truly the embodiment of great literature--certainly has the credentials to teach us how to discover wisdom in reading great literature. "We read . . . to repair our solitude, though pragmatically the better we read, the more solitary we become . . . The deepest motive for reading has to be the quest for wisdom," Bloom observes. "Reading alone will not save us or make us wise, but without it we will lapse into the death-in-life of the dumbing down in which America now leads the world" (pp. 101; 278). In an era that celebrates Stephen King and J. K. Rowling, Bloom confeses that he watches reading die with "elegiac sadness" (p. 277), noting that he now has three criteria for literature: "aesthetic splendor, intellectual power, and wisdom." In his book, Bloom addresses the never-ending, "ancient quarrel" between poetry and philosophy (p. 208). In his opinion, we ought not have to choose between Plato and Homer, "though Plato wants us to choose;" we can appreciate both, as long as we recognize that poetry is superior (p. 63). I admire Bloom's infectious passion for reading, and much like his other books, WHERE SHALL WE FIND WISDOM? will inspire readers to discover the poetic wisdom of the Western canon. G. Merritt

Another fascinating book...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Where Shall Wisdom be Found? is another fascinating book by Harold Bloom. He (somewhat arbitrarily) chooses the greatest wisdom writers of all time, and his perspective on their work is very illuminating. He goes through the history of the western world and selects two authors from each time period. The couplets are Job and Ecclesiastes (books, not people), Plato and Homer, Cervantes and Shakespeare, Montaigne and Francis Bacon, Samuel Johnson and Goethe, Emerson and Nietzche, Freud and Proust, and Thomas and Saint Augustine. Even though I highly recommend this work, I disagree with much of what Mr. Bloom has to say. What makes it worthwhile is his invaluable commentary of the figures listed above - who they were, and the thoughts they express. However, nowhere in the book does Bloom give us HIS definition of what wisdom is - and everything is judged by his own very personal standards. Literary criticism is, by definition, subjective; and it is Mr. Bloom's own personal prejudices that may put some readers off. In his defense, at least he is honest about his prejudices. "I agree with absolutely nothing in The City of God, but then the book is not addressed to a Jew and a Gnostic." Mr. Bloom constantly reminds us that he is not a philosopher; so, in the battle between literature and philosophy, he continuously asserts that we prefer literature. He considers Plato the greatest philosopher, but casually tosses him aside with preference to Homer, Cervantes, and Shakespeare. In trying to decipher his criteria for wisdom, it seems to center on useful aphorisms. It seems to be the reason he prefers literature rather than carefully constructed philosophical arguments. I had a logic teacher who uses to disparage maxims as "bumper sticker philosophy," and I think he has a point. Also, in this stage in his career, Mr. Bloom has lost sight of who the true enemy is. He continues a pointless and wrongheaded feud with Stephen King and J. K. Rowling as `enemies of literacy.' Nothing could be further off base. He writes that his criteria for reading are "aesthetic splendor, intellectual power, wisdom." These are not the only criteria - sometimes you just want a good story. And, if I may be a philistine for a moment, I do think you can find a bit of wisdom even from Harry Potter, unless you are determined not to find it. At a reading, Mr. Bloom said he should have included Kierkegaard, who keeps popping up in this book. I think Kierkegaard would have illuminated much about wisdom. It is not so much about saying that Plato is wrong and Shakespeare is right, but about one's own commitment to a belief system. Bloom rightly points out that literature holds a mirror, not to nature, but to ourselves. We find the wisdom in books that we are looking for. Mr. Bloom's wisdom may not be yours.

Complex and thought-provoking

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Harold Bloom is unquestionably one of this country's academic literary heavyweights. He has taught at Yale for many years. The listing of his books preceding the title page of this, his latest production, runs to 28 items. His opinions are strongly held, closely argued, often idiosyncratic, and never superficial. He seems to have read, digested and remembered not only all the works he is discussing, but also all the published critical comment on them down through the years. The subject of this book is what Bloom calls "wisdom writing," a term that pretty well explains itself. The unspoken corollary, of course --- one that Bloom never really acknowledges --- is that each reader will have his own list of "wisdom" literature and that no two lists will exactly agree. Bloom's list begins with Plato and gets no closer to our own day than Proust and Joyce. The two major Gods in his pantheon are Shakespeare for poetry and Cervantes for the novel. Others who earn high marks from him include Sir Francis Bacon, Montaigne and Samuel Johnson. There are some surprises on his roster --- the anonymous authors of those parts of the Old Testament known as the Kabbalah or Hebrew Bible, the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas and Sigmund Freud, to name three. Americans who earn places on his team include Emerson and, on a slightly lesser level, Walt Whitman. All of these authors and a number of others (Goethe, Saint Augustine) are discussed in densely packed and allusive prose. Bloom comes across as an academic writing mainly for his fellow academics. He has, however, one gift that many of his fellow academics lack --- he communicates well his own enthusiasm for the works he is discussing. You may not agree with all of Bloom's judgments and you may not understand what he is trying to tell you in his knotted prose --- but you will know that these are books and authors that matter deeply to him. If you go back to those you may not know and reacquaint yourself with them, he will have achieved his purpose. The book often reads like a transcript of graduate-level college lectures or perhaps the gist of a learned literary seminar. But every so often Bloom sets off a colorful aphoristic skyrocket that for a moment lights up not only his subject but also his own mind: Sometimes, while reading THE ILIAD, he says, "you get the impression that the gods are a storytelling convenience" who "live on forever, perfectly cheerful as they contemplate our sufferings." Nicely put. Bloom's admiration for Shakespeare brings him back time and again to two characters, Hamlet and Falstaff, who seem to him to most perfectly embody Shakespeare's world and wisdom. Safe choices, perhaps, but argued with uncommon gusto. His characterization of Goethe centers on the man's "paganism." His chapter on Proust wanders off into a dense literary thicket on the subject of jealousy. There are indeed many spots in this book where even the well-educated and careful reader will have to go back over a sentence o