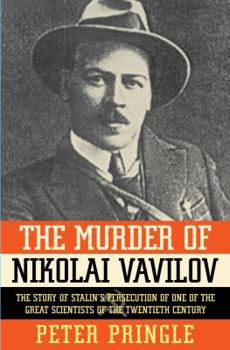

The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov, acclaimed journalist and author Peter Pringle recreates the extraordinary life and tragic end of one of the great scientists of the twentieth century. In a drama of... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0743264983

ISBN13:9780743264983

Release Date:May 2008

Publisher:Simon & Schuster

Length:370 Pages

Weight:1.35 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 6.5" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Founder of the world's first Seed Bank a century ahead of "Doomsday Vault"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

A remarkably relevant account of the cost of putting together the first seed bank collection that the word is just beginning to appreciate as crop varieties' diversity begins to disappear; and the cruel price paid by the most brilliant Russian botanist-geneticist for helping feed his countrymen. Such a clever read.

Great book on a great scientist

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

I really enjoyed this book. It provides a fascinating and even chilling behind the scenes look at the deliberate destruction of Soviet biology from Lysenkoism by following the amazing life and ultimately tragic death of Nicholai Vavilov, perhaps the greatest applied plant biologist, agronomist, and plant collector and explorer of the 20th century. Vavilov was a brilliant and charismatic man who was not only respected for his intellect but who was admired and even loved by almost all who met and came to know him. Many prominent foreign biologists thought the bright and charming and tireless Vavilov represented the best of Soviet science, and he did more to foster international cooperation and communication between biologists and especially agricultural biologists than perhaps any other man of his age. His contagious enthusiasm for the task he had set for himself--to better feed Russia and then the whole world--was contagious itself and he inspired literally hundreds of capable followers. He was blessed with a sunny disposition, perpetually optimistic outlook, and boundless energy. He had a generous nature and rarely had an ill word for anyone, including, amazingly, the Lysenkoist and Stalinist hacks who tried to destroy him. If Vavilov had one fault in his character it was that he tended to see only the good in people and not the evil, which eventually came back to haunt him in the person of Lysenko and his followers, when he finally realized too late that he needed to defend himself. But if there was one bright spot in the otherwise unbroken drab gray of Stalin's dreary and repressive Soviet Union it was the irrepressible Nicholai Vavilov, who almost single-handedly brought Soviet agriculture into the 20th century when before Russian crop yields were still at 19th century levels and only 1/3 of what was being attained in Europe and the U.S. It's especially sad and ironic that he was one of the many who died of starvation in Stalin's prisons, because millions of people in the former Soviet Union are alive today because of the greater yields from Vavilov's research, and the superior varieties he discovered, propagated and tested, and disseminated through the hundreds of agricultural stations that were under him during his tenure. The neglect and persecution of Vavilov by Stalin is even more ironic if one considers that when Germany invaded Russia, Vavilov's enormous seed bank--containing over 250,000 different varieties and samples and the largest in the world--was considered so important that it was on the list of significant cultural and scientific treasures to bring back to Germany. One fascist's bane is another fascist's boon. I enjoyed this book for several other reasons, not the least of which was that I have a small connection to Vavilov's story. In the late 70s when I was a doctoral student in biology, his sad case was still remembered by a few biologists, and I was one of them. At the time, the Cold War was still on, and I used the cas

The One Lysenko Deposed - A Scientific Tragedy

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Science is a wonderfully self-checking system. If science has data and explanations, it does not matter what governments think, or religions, or even a majority of people. Science isn't out to please partisans or appease dictators; when governments have insisted that science support particular explanations, the result has not been good for science or for government. The supreme example of this was Josef Stalin's support, on political principle, of the self-taught botanical quack named Trofim Lysenko. The disgrace of the Lysenko affair is well known; less well known is Lysenko's scientific rival, Nikolai Vavilov, whom Stalin and Lysenko arranged to be arrested and purged, and whose ideas were scrubbed from Soviet science until rationality resumed. Just what science and the Soviet Union and the world lost is told in the fascinating _The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov: The Story of Stalin's Persecution of One of the Great Scientists of the Twentieth Century_ (Simon & Schuster) by Peter Pringle, a British journalist and longtime Russia watcher. The story is a human one, however, and deeply tragic; Pringle has produced a clear and sympathetic biography of Vavilov, while also summarizing some complicated history and science. Stalin didn't like genetics, preferring older ideas of inheritance which would support how one generation could suffer but bring forth a stronger generation, bourgeois could produce Bolshevik. Nikolai Vavilov was born in Moscow in 1887, and went on to study in Cambridge where he got a strong education in the newly-rediscovered ideas of Mendel. From 1916 to 1933 he made expeditions to five continents, hunting up lost specimens and seeds. There was danger, natural and man-made, in such exploits, but he was an inspiring figure, a sort of Indiana Jones, delighting in the work and full of infectious enthusiasm. He had Lenin's support, but Lenin died in 1924. Stalin preferred the "barefoot scientist" Lysenko, who was an uneducated peasant with the knack for self-salesmanship, and promises that he could "educate" wheat to make an Eden of Russia's wastelands. Stalin was impressed, and eventually Lysenko was in charge of Vavilov and all of Vavilov's research facilities. Lysenko denounced Vavilov as a purveyor of Mendelism, and under the cover of the start of WWII, Stalin's secret police made their arrest; Vavilov had international contacts and there would have been an uproar during peacetime. He died three years after his arrest, of malnutrition; he had tried to harness real science against famine, and starvation got him in the end. It was a tragic end, a terrible waste of an extraordinary mind. After Stalin's death in 1953, Lysenko managed to gain power under Khrushchev, but after Khrushchev was ousted, Lysenko's skills in self-promotion failed, as science simply passed him by. His damage, however, to the academic discipline of genetics was to wound science in the Soviet Union for decades, and since his own theories were non

A Victim of Stalin's Purges

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Nikolai Vavilov was born in 1887, son of a prominent Moscow merchant. He was educated as a plant breeder, using the recently re-discovered work of Gregory Mendel about how inherited traits were passed from generation to generation - elevating plant breeding to the status of a science. By combining plants with desirable qualities, plant breeders could create superior seeds - seeds that were more resistant to disease, produced higher yields, consumed less water, and required shorter growing seasons. In order to do his work, Vavilov believed he needed easy access to a wide variety of seeds. He devoted his life to creating a seed bank, personally going on expeditions all over the world. In the process, he earned the reputation of being a tireless worker, brilliant organizer, and superb scientist. At a young age, he became the head of a major agency in Moscow, dedicated to improving and overhauling Russian agriculture. Then along came Stalin. Like many other accomplished citizens from Russia, Vavilov became a victim of one of Stalin's purges. He came from a wealthy family, was not a communist, and was friendly with some of Stalin's enemies. He was arrested in 1940, charged with serious crimes that were fabricated; then was tortured, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to death by firing squad. Later, his sentence was commuted to 20 years in prison, but his jailors starved him to death in 1943. This book flows like a novel and documents his story and that of his nemesis, Lysenko, who captured Stalin's fancy but ruined Russian agriculture for a whole generation. Vavilov spent his whole life experimenting with seeds. His innovations brought about huge strides in knowledge that could, at least theoretically, eliminate world hunger. In reading this account, I was struck with the serendipity factor that causes one scientist to be remembered over another. The young Charles Darwin was captivated by the way species changed over time. Newton dealt with gravity, planetary motion, physics, and calculus. Einstein's theories refined and modified Newton's work. Maxwell discovered electromagnetic fields and documented them mathematically. Madame Curie made significant discoveries about radiation. Bohr and Schrodinger developed quantum theory. Each of these scientists has attracted biographers. The story in this book suggests they probably didn't work any harder or more intelligently than Vavilov, yet they are all much better known. What they (perhaps accidentally) spent their lives studying, for whatever reason, was deemed more worthy of renown than the science of improving agriculture through genetics. Also to his credit, Vavilov appears to have had more positive personality attributes than most, if not all, of the above. This is a guy you would like to be around. Anyway, "The Murder of Nikolai Vavilov" is a fascinating read about a remarkable man who stood out as one of the best scientists of his generation - highly recommended.

The world's most famous and important unknown scientist.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Until Peter Pringle's brilliant new book, only a few specialists in the west knew anything about Nikolai Vavilov. Yet every visit to every grocery store, to every farm market, to every harvested plant and animal in the world owed a huge debt to a person who, ironically enough, was starved to death by Stalin in 1943. Pringle uses his own vast experience as a correspondent in Russia to gain access to many of the people who knew about, or worked with Vavilov. He also was given access to a vast collection of personal correspondence and photographs that flesh out the characters involved. The work is written in rich, detailed and at times emotional prose. This book will be enjoyed by anyone who wonders how politics can influence science, scientists, science policy and the rest of us as the consumers of science. The book is about the past but - unfortunately - the content is very relevant to today.