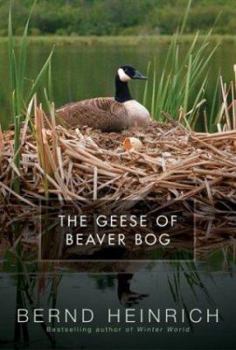

The Geese of Beaver Bog

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In the summer of 1998, award-winning writer and biologist Bernd Heinrich found himself the unwitting -- but doting -- foster parent of an adorable gosling named Peep. Good-natured, spirited Peep drew... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0060197455

ISBN13:9780060197452

Release Date:May 2004

Publisher:Ecco Press

Length:217 Pages

Weight:1.15 lbs.

Dimensions:0.9" x 6.1" x 9.0"

Customer Reviews

6 ratings

Really inappropriate interference with nesting geese

Published by Brittany , 3 years ago

This book was horrible. Canada geese are protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and it is illegal (not to mention really unseemly) to tamper with nests and eggs. This book just chronicles his constant interference with these nesting geese. He even approaches the gander to the point where it tries to attack him, and removes eggs from the nest and dips them in the cold water. I have no idea how he got away with writing something like this without a ton of backlash. As a biologist you would think he would respect wildlife enough to keep a safe distance. Really difficult to read, I couldn't even finish it.

This is a wonderful book!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

The Geese of Beaver Bog is a wonderful book. It's a several-years-in-the-lives account of the title's geese as well as the bog's other inhabitants. The author, Bernd Heinrich, is a professor of biology but this isn't a formal study of goose social lives. It's just a chronicle of the observations he made of the animals living in the ponds around his Vermont home. The main part is science light, though Heinrich appends a few, brief essays and a bibliography that discuss theory and direct readers to more "scientific" literature. And the bog contains quite a collection of individuals. The "Summer of Love" never ended here as Heinrich witnesses mate-swapping and sybaritic promiscuity that would have Focus on the Family howling with dismay. But he also witnesses the adoption of stray goslings and the care parents take to make sure their children survive. Heinrich establishes quite close friendships with four geese in particular: Peep, Pop, Jane and Harry (the wife-swapping pairs mentioned above), and he observes behaviors that aren't in the "geese textbooks" but reveal these birds as intelligent, feeling creatures who are not wholly governed by genetic programming but are independent actors. One of the more interesting behaviors was a migration of parents and young from Heinrich's bog to a smaller pond a couple of miles away (which occurred every year that the author observed the geese). At first glance, it would appear insane to cross two miles of predator-infested woodland (including a manmade road) trailing days-old goslings. Heinrich reasons that, in part, the more open landscape of the second pond afforded a more comfortable environment for the geese, who evolved in tundra-like conditions. The manifest dangers were less of a cost than the benefit of the psychological comfort afforded by a wide open, defensible pond (a good bet on the geese's part since in both migrations observed, the entire families made it intact). It's a human tendency to overgeneralize so that we speak of "the black community" or "evangelicals" or "the American people" as if these were real groups, all of one mind and body. Yet, when one flies closer to the ground, all the peaks and valleys, forests, and rivers come into sharp focus. That's one of the most attractive features of this book. By flying so close to the ground, Heinrich and his readers come to see the geese for the individuals they are. I was planning on giving this book three stars - I "liked it" - but the last few pages actually made me sit up (literally, since I began looking for a piece of paper and a pencil to write down my epiphany). A light went off in my head as Heinrich inadvertently managed to articulate a philosophy of moral ecology that I had been seeking for years in order to justify how I felt about the world around me and how we should treat it. Essentially it comes down to two principles: 1. Every creature has the right to life but that right is circumscribed by the ecosystem's right to surviv

Getting to Know Geese

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This book chronicles the lessons Heinrich learned while observing geese in his back yard. In 1998, Heinrich's son was given a wild gosling, Peep, which the family raised. When Peep grew to maturity, she remained friendly with the Heinrichs, giving Bernd Heinrich an ally into the world of wild geese. In subsequent years, Peep returned from winter migrations to a pond near the Heinrich's back yard, and permitted Heinrich to approach and observe her nesting attempts. Over the next few years, Heinrich observed not only Peep, but several other geese that he got to know through Peep. Through these observations, Heinrich found may be serially monogamous rather than strictly mate for life, and that geese must struggle for survival not only with other creatures, but also with other geese who may be perhaps "jealous" of their success. The book is a fascinating window not only into the social life of geese, but also into the mind of a scientist and observer of the natural world.

Bernd's "Beaver Bog" boggles!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

After a few chapters, the number of "5:30 AM" entries seem staggering. While i'm struggling to figure out which end is "up" on the coffee-maker, Heinrich is already out in the field. He's watching his subjects, talking to them and offering them handouts, and recording their behaviour in meticulous detail. The rewards, he demonstrates with enthusiasm, are many and fruitful. His descriptions are certainly a rewarding read - even if i have to have a nap before commenting on them. Heinrich chose his home location well. The countryside of Vermont offers rich pickings for a naturalist and this one has taken full advantage of that situation. In this book, he ventures to a set of ponds created by beaver dams. Beaver and muskrat lodges make ideal nesting sites for geese. The two creatures don't disturb each other and the isolation keeps predators away from both. Heinrich expects geese and isn't disappointed. They arrive, take up station, fend off later visitors intent on occupying the same territory, mate and produce eggs. Heinrich dutifully records all the activity - sometimes with unexpected precision: "She slept four minutes". At first, it all seems like another naturalist's jaunt into the woods. Interesting and enviable, but does it mean anything to us? Heinrich, however, is surprised by what he observes. Not the least unexpected is the book's opening - an adult goose pursuing his pick-up along a road at 60 kilometres an hour. There are other, more compelling mysteries. In an engaging account of "Pop" and "Jane" producing a flock of goslings, Heinrich discovers the entire mob has disappeared from the nest. He'd already tested the couple's attitude toward him by reaching under the incubating female to check the condition of her eggs [try it! i'll just watch from over here]. Tracking their likely path, he discovers a colony of geese and goslings some distance from their home ponds. Even more astonishing is the fact that the number of parents and goslings don't properly match. Some of the parents have left their offspring to the care of "gosling-sitters" and flown north. Why would geese abandon their young when other birds spend enormous amounts of time and energy supplying and teaching theirs? Heinrich's answer is an excellent study in evolutionary strategies. He discusses different species and various environments. He unashamedly uses human metaphor to describe various survival strategies among different animals. Why not? That's due to the long history of animals developing methods for survival and reproduction. Many of these techniques will be similar in some conditions, different in others. All can be assessed in terms of success and the likely logic isn't difficult to impart. Heinrich can describe it better than many, carefully and clearly imparting his own reasoning. With a persistence many should envy, he made his observations in every circumstance possible. He recorded dutifully and brings those observations to

Loved it!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

This is an intimate story of Heinrich's relationship with a hatchling Canada goose he raises who later voluntarily goes to the wild. She later returns to him and the marsh and he begins studying her and other pairs of geese. If you like geese or are interested in wild animal behaviour this is a must read. It is written in an emotional style that I just couldn't put down. He is such an expert at understanding animal behaviour. At the back of the book he discusses Conrad Lorenz' book: Year of the Greylag Goose which I had read years before.

A scientist's eye and a writer's eloquence

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

The serendipitous adoption of a gosling sparked several years' close observation of her species as they nested in the bog near biologist Heinrich's Vermont home.The bog itself, with its variety of teeming life, provides a rich background community, illuminated by Heinrich's breadth of knowledge, curiosity and eloquence. Heinrich's ever-present sense of wonder ("Winter World," "Mind of the Raven") animates his keen scientific eye, quickening a corresponding fascination in the reader.His observations of geese, "peripheral to swamp watching," began in 1997 when a pair of Canada geese nested on a hummock in the beaver pond where Heinrich came every dawn, mostly to observe the beavers. Habituating himself to the pair, he expected to be able to enjoy a summer of observing their family life, but the day after the goslings hatched, the whole family disappeared, not to be seen again. The same thing happened the next year, and the next.Meanwhile, in 1998, Heinrich's toddler son acquired a day-old Canada goose, Peep. In just a few short paragraphs Heinrich conveys the manic difficulties of raising goose and toddler together over a summer, and the regret and relief when Peep disappeared one day, presumably to join one of the migrating flocks overhead. It was two years before he saw her again - standing on his gravel driveway with her mate at dawn, after announcing her presence in a raucous flight around his house.As Peep and her mate, dubbed Pop, showed signs of trying to nest (although Peep was a year younger than the usual nesting age) at the bog pond, Heinrich's enthusiasm for goose watching reached new heights. Often arriving before dawn, he observed the interactions between the resident pair and Peep and Pop as well as other geese that came to the bog looking to nest.The fights were noisy, dramatic, and puzzling, since there was plenty of room and food for all. But the resident pair drove off all comers and Peep and Pop finally chose a less desirable area nearby. To Heinrich's delight, Peep laid some eggs and the pair settled in. But Peep was not as attentive as older mothers tend to be and her nest was attacked more than once, its eggs tossed out. Though Heinrich did not catch them in the act, he suspected the resident geese in the adjacent pond, as the eggs were not eaten.While observing Peep and Pop's trials and tribulations as well as feeding and pair bonding behavior, and the dramas enacted between other geese, Heinrich also notes the inexplicable antics of the red-winged blackbirds, the forest-shaping habits of the beavers, and the baby-sitting behaviors of grackles, among many others. He relates the process of habituating the geese to his presence and how Peep's treatment of him differed from that of the wild geese. Though none ever went so far as Peep and her reluctant mate who visited his yard daily whenever possible, Jane (the resident goose in the main pond) allowed him to examine her nest, even after the eggs had hatched.Watching the geese o