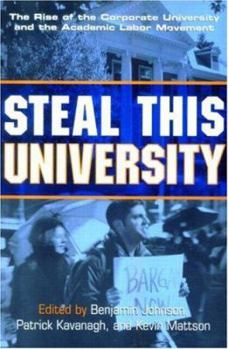

Steal This University: The Rise of the Corporate University and the Academic Labor Movement

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Steal This University explores the paradox of academic labor. Universities do not exist to generate a profit from capital investment, yet contemporary universities are increasingly using corporations as their model for internal organization. While the media, politicians, business leaders and the general public all seem to share a remarkable consensus that higher education is indispensable to the future of nations and individuals alike, within academia...

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0415934842

ISBN13:9780415934848

Release Date:July 2003

Publisher:Routledge

Length:265 Pages

Weight:2.20 lbs.

Dimensions:0.7" x 6.1" x 9.1"

Customer Reviews

4 ratings

a cogent and clear analysis of the university from the academic worker's p.o.v.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Of the books I have read thus far on the corporatization of the university, this is by far the clearest and most direct. Steal this University has some poignant essays in it, in particular the one by the MFA artist who has spent years as a freeway flier in Southern California. Also very enlightening is the essay on the "merit system" for tenure line and tenured profs, and not only, how unfair it is (which I, as a UC employee already know), but actually how expensive and inefficient it is to run. What I think is missing from the book (and from others like it) and what another reviewer has commented upon is the student perspective and the other odd market forces at work, as well as the ongoing mystery as to why higher education gets more and more expensive for the student, while the pay-scale for everyone other than top administrators seems frozen or going down. The final issues seem crucial to get answers to, if we are going to have any chance of improving the status quo.

Who Are the Perpetrators?

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This collection of essays is well organized to outline the key higher education issues of corporatization, organizing, what it's like to be a non-tenured faculty member unsure of their next contract. Casual labor is here to stay, but solutions to current problems are few and far between. Tenure battles, personal stories of anguish, and barriers to unionization provide the reader a thorough and actually entertaining escape from their own problems resulting from the increased use of contingent faculty. Although it appears as that the University of Phoenix is being singled out as the great perpetrator, the fact the students have a choice is overlooked. There are more University of Phoenix style schools out there, some of which are being organized with tremendous entrepreneurial funding sources and will probably eclipse Phoenix. The diverse array of assembled writers and editors adds variety and perspective to this book.

Tenure tracks derailed: the triumph of the "at will"

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

The other two reviews accurately reflect logical perspectives on the clash of the dwindling but nevertheless delighted adepts securely tenured in the guild, the restless hordes of journeymen "freeway flyers" doomed to adjunct/part-time work (or in my case, full-time, non-tenured at a corporate university [not U of Phoenix, thank heaven for small mercies] which grants nobody tenure but everybody must work on an "at will" agreement sans contracts), and the eager if exhausted grad students, the apprentices. Benjamin Johnson's edited this collection of accounts, which range from overviews of the situation to analyses of the corporatization effects on higher education, union efforts, and a critique by David Noble (see his "Digital Diploma Mills" for more of same). Ana Marie Cox, whose essay is not really about Phoenix per se as much as the profit-making universities--disdains the proprietary system and makes the negative observations that are largely accurate, and to be expected. As one from within such ivy-less, for-profit walls that Cox evidently has not entered, what this essay (and book) lacks, however, in my judgment is the first-person testimony of a faculty member from the ranks that Cox and all other contributors shrink away from as if they'd come into contact with lepers. The essayists understandably bewail their fate, lest they end up--desperate and humiliated after graduate matriculation at the Ivies and East Coast elites--at such an institution. I see from the notes appended that all but one of those with PhDs, no matter their earlier travails, are employed full-time now at universities. Nearly all of those with doctorates (reading between the lines of some descriptions?) seem now on tenure-tracks; Cox alone went into journalism on- and then off-line; two more are doctoral candidates, the remaining two are union organizers. One PhD who has not entered the ranks of the blessed, artist Alexis Moore, shares with me an Angeleno experience of commuting and teaching all about this vast gridlocked expanse, and the fact that she continues to do so in such a journeyman fashion. Her account, as with Kevin Mattson's narrative that includes tellingly a stint of one class taught in a shopping mall at a community college branch, should remind those who declaim solidarity and radicalism from their tenured lecterns that they also are in part responsible for perpetuating not even the status quo of tenure even as a hope to the worthy one in a hundred applicants, but as smug contributors to its decline. How many salaries at the top, administrators, full profs with two or three courses a year, football coaches, fundraisers, are paid so generously thanks to the "surplus labor" of many more adjuncts, with six courses to teach, as scattered across three colleges a semester? Johnson notes that one in three tenure-track positions recently opened up by boomer-retirees are filled with tenure-track candidates; the rest are divvied up into cheaper disposable part

a reader too reactionary

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

a reader, you are clearly ignorant of the realities of adjuncting and grad school, and why it is not acceptable for universities to make hefty profits off of their students and then turn around and pay adjuncts and grad students sub-poverty wages. The class I'm teaching right now at a state college pays $2800. I'd have to teach ten classes a year to make $28k! Four and four is the 'normal' load...lets see *you* teach four classes and then come home and read a little critical theory so you can finish your Phd. What a reader sees as 'back to the sixties' and hostility is really a struggle by working people to make a living doing something they believe in, and what they believe in is being gutted of learning content and franchised and commercialized by corporations. Yes it's true, a reader, and you shouldn't make light of the struggle of working people and intellectuals to fight for the power of education. Pendejo.