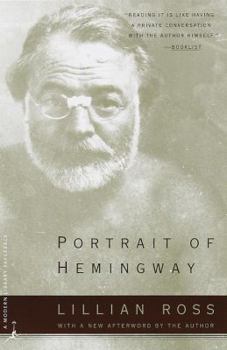

Portrait of Hemingway

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

On May 13, 1950, Lillian Ross's first portrait of Ernest Hemingway was published in The New Yorker. It was an account of two days Hemingway spent in New York in 1949 on his way from Havana to Europe.... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:0375754385

ISBN13:9780375754388

Release Date:July 1999

Publisher:Modern Library

Length:112 Pages

Weight:0.40 lbs.

Dimensions:0.3" x 5.5" x 8.7"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

CUTTING EDGE JOURNALISM AT THE TIME.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

What an interesting bit of writing this work is, in particular when you remember when it was written and the publication for which it was written for. This is a rather short, but in many ways intense account written by Miss Ross recording her meeting with Earnest Hemingway in 1950 and covers a period of two days. Whether you are an admirer of Hemingway or distracter makes little difference when reading this bit of work, and Miss Ross is breaking new ground here in the field of reporting and recording and indeed, in journalism. Quite a number of critics have been rather harsh with Ross, claiming that she rather took advantage of an author at a vulnerable moment in his life, i.e. at the times things were beginning to unravel and the alcohol and mental disorders were in the process of destroying a wonderful mind. It has been claimed by various biographers and family members that the entire piece was geared to enhance Ross and further her career at the expense of the great writer. I actually don't see that here. I sense genuine admiration on Ross's part, even though she, the author, has taken great pains to be non-obtrusive. On the other hand, she was indeed a close friend of both Earnest and his current wife Mary and despite what may have been said later, their relationship appears to have been genuine and close right up to the end of both of the Hemingway's lives. The style and technique of reporting Ross uses is her description of Hemingway, and later uses in her "Picture," which was a narrative of the making of Huston's film "The Red Badge of Courage," was quite fresh at the time. It deviated from the old newshound type of reporting where just the facts were presented and indeed manipulated in a rather formalized presentation. Here we have a sort of chatty, gossipy first person account, not shy of the gossip, recording conversations just as they were and not cleaned-up, so to speak. This deviated considerably from the pretentious and near unreadable sop that was flowing from the pages of The New Yorker, whom she was writing for at the time, and broke new ground. It was probably one of the better features to ever appear in this particular magazine, but then that sort of proves even a blind pig will find an acorn from time to time, if it spends enough time in the woods...I suppose the New Yorker no different in this respect. This technique of course was taken to new heights and refined by Truman Capote with his "The Muses Are Heard," his first hand account of the trip the cast of "Porgy and Bess" took when it visited Russia a few years later. This was a new type of journalism that Lillian Ross was experimenting with and it certainly worked out for her and hoards of others to follow in her footsteps. Did she take liberties here and there? I dare say she did. To counter that though, I suspect that Hemingway took some liberties with her also, and more or less played the part he felt she expected of him. From what I have read of

does what biographies of 'Papa' cannot

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 23 years ago

This slim volume covering a mere two days with Hemingway will take about an hour or two to read. However, it's merit is that it is presents us with a 'bird's eye-view' of Hemingway's later years, the alcholism, his relationship with his wife Mary, his son, and some of his old friends. It also gives us a glimpse of his feelings about his writing in his own words. For those who have enjoyed Hemingway's fiction and read biographies of his life, this book is a must.

A must read for Hemingway fans and fascinating overall.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Portrait is a glimpse into the life of Hemingway over a two-day period. For fans of Hemingway, this is a fascinating snapshot of the famous Hemingway bravado and an offering of the vulnerability and sensitivity flowing immediately under the gruff and overly-confident exterior. Hemingway's passion for art and alcohol is found here, and one can't help but be reminded of his earlier devotion to, and inspiration from, painting rendered in A Moveable Feast. Sadly, one also anticipates the later disability compounded by the excessive drinking that finally extinguished such a brilliant career. This book caused a commotion when it was first published because Hemingway came across as insensitive, but it is only the lazy reader not willing to dig a little deeper, and only the reader who allows the powerful prose of Ross to lull them into mere observation, who fails to recognize the whole of Hemingway's character. If you are a Hemingway fan, or you want to scratch the surface of the life of a great writer who showed no fear in displaying his faults as readily as his virtues, and you don't mind a few character quirks along the way, read this book.

A remarkable combination of objectivity and love.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

It's a remarkable piece of work, both loving and accurate. If you don't like his kind of macho, I guess you could call the Portrait barbed; but she obviously loved it and him enough to win his trust. He opened up for her and, in the welcoming sense, took her in. I'm left full of wonder for the way she got his words, as well as his presence, down. You can see, too, how his early work, with its pared-down clarity, influenced her style. This is biography without conjecture -- biography at its best.

Like having a private conversation with the author

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

This edition of Portrait of Hemingway by Lillian Ross starts with the 1950 Profile of Ernest Hemingway, one of the most famous articles ever to appear in The New Yorker, and ends with an Afterward by Miss Ross which she has now written, almost fifty years later. The profile became a classic, William Shawn wrote of it, "perhaps because, to a degree that has never been equalled in a factual portrait, it contains the very breath of life." Miss Ross does not present us with hints or rumors of Hemingway, or with theories or suppositions about him, or with second or third or fourth hand "information" downloaded and culled over the years from the writings of would-be biographers. Instead, on page after page of "Portrait of Hemingway," Hemingway is simply there. With the Profile, Miss Ross made several litarary innovations, one of which was to compose a portrait entirely in terms of action. For example, as Hemingway walks through the Metropolitan Museum with his son Patrick, he talks --exuberantly, at times reflectively, always brilliantly-- about his work, his pleasures, his plans, his notions. Miss Ross quietly, sensitively, and affectionately, sets it all down, as much of it as is needed to record, on paper, a living man -- and since the man is Hemingway, a great man. William Shawn, who edited the profile for The New Yorker called it a masterpiece. In the Afterword, Miss Ross tells about her friendship with Hemingway and his wife, Mary, that followed the publication of the profile and that continued until his death in 1961 and Mary's death in 1986. And again, Miss Ross gives us, not her own opinions or suppositions, but actual quotes from the letters the Hemingways wrote to her over the years. For instance, she quotes what he wrote to her in the mid 1950's when people continued to talk to him about the Profile: "All are very astonished because I don't hold anything against you who made an effort to destroy me and nearly did, they say. I always tell them how can I be destroyed by a woman when she is a friend of mine and we have never even been to bed and no money has changed hands?" Miss Ross also writes: "He had some succinct advice for me as a writer: `Just call them the way you see them and the hell with it.'" Miss Ross writes that she confided in the Hemingways about her romance with William Shawn ( She wrote that love story in her 1998 book Here But Not Here) and how supportive they were when she went to Hollywood in an effort to disentangle herself from that turn in her life. (She stayed there for a year and a half, doing the reporting for her Hollywood book Picture.) Hemingway told her things. She didn't hunt or fish or shoot or go on safaris to Africa, but she enjoyed hearing Hemingway talk about those things. Both Ernest and Mary wrote to her from Africa, the echoes of which may be found in the new Hemingway book True at First Light. They wrote to Miss Ross from their Finca, or farm, outs