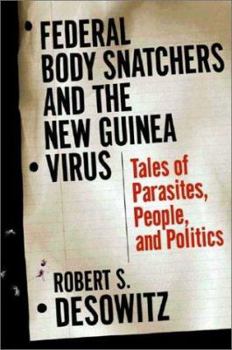

Federal Body Snatchers and the New Guinea Virus: Tales of People, Parasites, and Politics

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Twenty years ago the world slept, confident that biomedical science would protect it from devastating plagues. Our wake-up call sounded at the outbreak of the AIDS epidemic. Then came more unfamiliar... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0393051854

ISBN13:9780393051858

Release Date:October 2002

Publisher:W. W. Norton & Company

Length:224 Pages

Weight:1.05 lbs.

Dimensions:1.1" x 5.8" x 8.4"

Related Subjects

Biological Sciences Biology Biology & Life Sciences Clinical Diseases Diseases & Physical Ailments Education & Reference Epidemiology Health Health, Fitness & Dieting Health, Fitness & Dieting History & Philosophy Infectious Diseases Medical Medical Books Medicine & Health Sciences Politics & Government Politics & Social Sciences Reference Research Science & MathCustomer Reviews

3 ratings

Summary of recent parasitology efforts, worldwide

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Robert Desowitz has been associated with many of the recent efforts to control various diseases which are faciliated by parasites; I found his comments quite interesting.

Desowitz makes another hit!

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 20 years ago

Anything written by Robert Desowitz is always a worthwhile read and his most recent (and sadly, last) book, "Federal Bodysnatchers and the New Guinea Virus: Tales of Parasites, People, and Politics," is no exception. His expertise on human infectious diseases is impressive and thorough. He discusses the little known behind the scenes intrigues involved with the attempts to deal with malaria, West Nile virus, sleeping sickness, and several others. He also discusses the effects of global warming on the spread of infectious diseases and the roll of DDT in suppressing malaria specifically.His earlier book "The Malaria Capers" (1991) should be read to completely understand the political and even criminal problems that developed within the malaria vaccine research program. These problems landed some researchers in jail and certainly have added little or nothing to the development of a real vaccine. The vaccine is tough to produce (over 70 years has so far been spent on the search) because of the fact that Plasmodium falciparum (the main target of vaccines as it is the main, if not sole cause of death from malaria) is a much more complicated organism than the viruses and bacteria that are usually the target. Because of its complex life cycle and ability to avoid antibodies and parasite-killing cells, malaria soon escapes any vaccine so far developed. A Colombian researcher is supposed to have a 100% effective vaccine, but Desowitz is rightly skeptical. As I have not heard of the vaccine being a success, I will have to agree.The problems with DDT discussed by Desowitz demonstrate that there are no easy ways out. DDT was banned for agricultural use pretty much worldwide within a decade or so of the publication of "Silent Spring." It has since been used for malaria control in many tropical countries and has been more than a little effective, even though resistance had built up in mosquitoes in many areas (Desowitz notes that some researchers think that resistance was helped by the huge amounts of DDT used in agriculture). There is little doubt that DDT was an ecological disaster when it was broadcasted throughout the environment. However, there is a movement to ban it even for anti-malarial use and Desowitz thinks that this may be wrong-headed. I am not sure about this, but I have to admit that it is not my children that are at stake (at least for the present time!) However, if global warming continues (and neither Desowitz nor I am under any illusion that it will not) we may be staring at a lot of new and old diseases (including malaria- which has already made some incursions) that we never thought possible in the United States. Then we may sing a different tune!This book should be read by everyone concerned about emerging diseases, whether brought by terrorists or (much more likely) by human movement and trade. It should also open anyone's eyes to the lack of efficiency of many organizations charged with the protection of world and national

An authoritative look at the politics of infectious disease

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Epidemiologist Robert Desowitz gets a few things off his chest in this free-swinging frolic through the world of infectious disease with an emphasis on politics, economics and human stupidity. In particular he is not happy about the fact that Big Pharma doesn't find it cost effective to work on drugs that might save lives in Third World countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa, home of not only Ebola and AIDS, but perennial killers, malaria and sleeping sickness. He also doesn't care for the bad press that DDT has endured since "Saint Rachel" (p. 57) published her manifesto, averring that "Nothing has ever equaled DDT" for controlling "the spineless blood-suckers" (mosquito, fly, and tick vectors) that bring dengue, plague, typhus, malaria, sleeping sickness, etc. to our bodies, and that "no essential public measure [the use of DDT] has been so irrationally denied."He makes a good case. It seems that in saving the ospreys and the eagles and other creatures of the wild we have allowed disease vectors to flourish resulting in countless millions of human lives lost. This surprising point of view, however, made me realize once again the false dilemma that we often put ourselves into, that of "them or us." At some point our rapacious desire to increase our numbers at the expense of our planet home must cease otherwise we will find ourselves alone with our mice and rats, our cows and pigs, our cockroaches and our sheep, our fields of soy and wheat and selected parasites, the rest of nature gone the way of the dodo. Do we need more humans or do we need to save the rainforests? My answer is that we must reduce our numbers and live in concert with nature. Desowitz does not consider this larger point of view in his book. I wish he had.He does however realize that we need more doctors and that medical schools ought to let more people in. He notes that "Innovative teaching methods can now accommodate double the student intake," wryly adding that "This may force some of the doctors in the new, bigger pool to switch from BMWs to Buicks." (p. 56) He also wants the World Health Organization reformed, calling it "a too-politicized body, best at furnishing slogans." (p. 124) Additionally, he would like to see the big pharmaceutical companies rearrange their priorities. He laments how a drug called DFMO is being manufactured for use as a depilatory to rid women of "uglifying facial hair" (with glossy ads in Cosmopolitan, Gourmet and Bon Appetit magazines) when it could better be used to fight sleeping sickness in Uganda and Sudan. (p. 146) One of his pet peeves is the way our patent laws work in respect to genetic material--part of a "patent or perish" syndrome. (See page 203.) He quotes then US secretary of commerce Ronald Brown to the effect that genetic material can be taken from you and patented for the enrichment of someone else and there is nothing you can do about it. (p. 200) Some people call this "biopiracy." (p. 193)In the later chapters