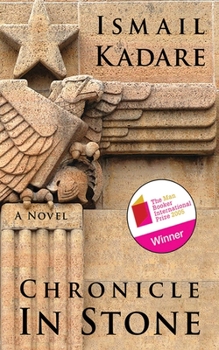

Chronicle in Stone

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

Chronicle in Stone...is epic in its simplicity; the history of a young Albanian and a primitive Albania awakening into the modern world.--Michael Dregni, Minneapolis Star Tribune This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Paperback

Language:English

ISBN:161145039X

ISBN13:9781611450392

Release Date:July 2011

Publisher:Arcade Publishing

Length:320 Pages

Weight:0.75 lbs.

Dimensions:1.2" x 5.5" x 8.2"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

A Darkly Humorous Story of Impending War as Seen through a Child's Eyes

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Throughout the Cold War era, the Albanian People's Republic was ruled with an iron hand for nearly fifty years by Enver Hoxha, a man virtually unknown to the West. Thus, it is certainly by no means accidental that Ismail Kadare sets his wry, satirical novel, CHRONICLE IN STONE, in Hoxha's (and, remarkably, Kadare's) hometown of Gjirokaster, an ancient stone town not far from the Greek border. Hoxha actually appears as a marginal character in the story as a Communist partisan sought by the invading German army. In addition, and presumably biographically, the author at one point mentions in passing that among those lost to a recent aerial bombardment was one L. Kadare. In the early years of World War II, Gjirokaster suffers the travails of an essentially defenseless city, overrun first by the Italian Army, then the Greeks with the assistance of the British Royal Air Force, and eventually the Nazis before finally succumbing to the oppressive thumb of Stalinist Russia. The uneducated townfolk, still heavily prone to superstition and fantastical beliefs, exchange rumors of a red-bearded man, Yusuf Stalin, who will drive out the unwelcome invaders. "Is he a Muslim?" one character asks another. After a moment's hesitation, the other replies confidently, "Yes. A Muslim." "That's a good start," the first answers. Later, it is the infamously sun-glassed Hoxha who is believed to have started a new kind of war, the one that brings the Germans to Gjirokaster. Kadare hilariously personifies the absurd effect of this constant changing of hands. Albanians leks become Greek drachmas, then Italian lire, then back to leks again. At one point, a plane drops leaflets on the town that begin, "Dear citizens of Hamburg." When the Italians first arrive, a lesser resident named Gjergj Pulo changes his name to Giorgio Pulo, then to Yiorgos Poulos when the Greeks take over. He dies under the German occupation just after having applied for another name change, this time to Jurgen Pulen. The townswoman whose business it is to prepare the make-up for brides on their wedding day is given to repeating the phrase, "It's the end of the world," at every news event and new revelation. CHRONICLE IN STONE is narrated through the eyes of an impressionable young boy, perhaps eleven or twelve years old. In the first third of the book, events are seen almost entirely through the boy's impressionable and naïve eyes. After he discovers a book by Jung and reads "Macbeth," however, those eyes seem to take a gradually maturing and more jaundiced look at his surroundings. In fact, Kadare uses multiple references to sight and blindness throughout much of the book. Early on, his boy narrator even likens blindness to a stopped up toilet, where the many sights a person has taken in have somehow formed a blockage that prevents new ones from passing through. Kadare revels in the boy's sense of wonder, his susceptibility to superstition and magical occurrences, and his lack of appreciation (and f

A Boyhood in World War Two Albania

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Ismail Kadare's "Chronicle in Stone" is a window into the world of World War Two Albania. The trials and times of a small Illyrian town as it weathers yet another occupation by foreign soldiers and yet more war are put to paper in this magical recount of the author's own experiences as a child. The extraordinary feature is that the reader sees into this window through the eyes of a young boy, and the descriptions of this town of stone, Gjirokaster, are what make the book so prominent. Kadare gives this ancient city a life all its own both as a whole and among its elements in his tale. When the boy narrator coos into his house's water cistern, it isn't an echo that replies but the cistern itself, and he ponders the feelings of an old and lone(ly) anti-aircraft gun that guards over the city. The author in this work has given the reader several themes in this one novel of a city and its boy. We see post-Ottoman, post-Great War and post-independence Albania as it sits under Italian occupation, which never figures much in the boy's or the other residents' minds much until the city becomes a battleground for Italians and Greek armies. We see the new modern generation taking shape, in the form of two youths--one of whom causes an uproar by donning glasses to correct his vision, glasses being an eternal metaphor for the educated intelligentsia--who speak Latin to each other as a secret code and a rebellious young aunt who runs off to join the partisans. We see the richness and complexity of the simple lives played out in this ancient city, despite the hardships caused by Allied bombing. Finally, we see the convulsion of a world gone mad as the city is emptied of its inhabitants and then overrun by "the men with yellow hair," the Teutons from the north. Throughout it all the boy relays this enormous world as he sees it through his young eyes. "Chronicle in Stone" brings a deeply rich Albania to life.

Lyrical and tragic story of a city - and a boy - caught between two worlds

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 18 years ago

Ismail Kadare's Chronicle in Stone is the tragic story of a city steeped in history and Old World traditions that is forced to change or be destroyed by the madness and brutality of twentieth-century warfare. The story is told through the eyes of a child, and just as the narrator's innocence and sense of wonder are lost forever as he comes to understand the violent nature of all that is happening around him, so it goes with the city as a whole, which also loses something irrevocable as it is wrenched from its sleepy, timeless existence into the chaotic modern world. The choice to use a child narrator heightens the sense of immense change that the city is undergoing, for this child sees the city's buildings, streets, and bridges as living entities which shift and move and change their mood from day to day, one day seeming to offer firm comfort and shelter, and the next seeming menacing and hazardous, depending on the weather, the attitude of the people around him, the relative brutality of the occupying army, and the intensity and closeness of the bombing campaign. In the stone facades, steep winding streets, and rain-streaked rooftops of the city, the narrator personifies the desires and sufferings of his people, but he does so unselfconsciously, for he is merely reporting what he sees and feels, because for him the city really is alive. As a child, he is also able to report what he sees with a peculiar mix of detachment and awe that would not be possible from an adult. When the city is bombed, the emotion he feels above any other is pride in the fact that his house, as one of the biggest and strongest in his neighborhood, is chosen as a bomb shelter. For him, the bombings, as well as the occupation of the city by the Italian army, are simply facts of life - just the way things are and always have been for him - and he doesn't always understand the anger and bitterness of the adults around him. There are many things to admire in this novel, but what I admire most, I think, is the way Kadare unfolds the story and conveys the grand scale of the tragedy but manages to do so in a way that is very personal and easy to connect to. He conveys character very effectively and economically-- with a few sentences of dialog, he gives us a very clear picture of the family and neighbors of the narrator, their individual quirks of personality and beliefs, as well as what the narrator thinks of them. He also disperses throughout the narrative brief fragments of a chronicle of the city, as written by one of its eccentric residents, and this interwoven chronicle lends a greater sense of the historical context of the events as they unfold. As the chronicle gradually becomes less and less coherent, we become aware of the effects of the chaotic violence on the mind of the chronicler, and by extension, the minds and hearts of everyone in the city. By the end of the narrative, the child has seen many horrific things, but has also known

Everybody's got a cistern in their heart somewhere

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 24 years ago

Gjirokaster, Albania. Not a spot that rings a lot of bells for most people. But if you read this brilliant novel, you will never forget the place, even if you never actually get there. Once, four years ago, I did go there. Square gray houses rise from the steepest, most outlandish spots, houses made in the Ottoman merchant style of the mid-19th century, half-fort, half-mansion. The narrow streets wound around the hillsides that looked out over a vast green valley, snow-capped peaks towering into the clear blue sky. Grape arbors and trees poked over walls, quiet passersby disappeared into crooked alleys. A small boy guided me to Kadare's house. I wished to see the cistern underneath, the one that trapped all the raindrops that "recalled with dreary sorrow the great spaces of sky they would never see again". But the house was closed. The descriptions of the house--fictional or actual--made me recall how I imagine the house of my own childhood. Higher up the hill, after twisting through more lanes of stone, I came to former supremo Enver Hoxha's house, recently turned into an "ethnographic museum". A scorpion skittered across the floor and I killed it. I visited the great vaults under the citadel where the citizens escaped the bombings. The whole town was alive for me because I had read CHRONICLE IN STONE. Other great writers bring Paris, London, Moscow, New York, or Tokyo to life. Kadare has put Gjirokaster on the list of immortal towns with this volume. It is a wonderful book of a town and its bad times-from 1939 to after the end of World War II-through the eyes of a boy. In his usual style, the author weaves many thoughts, dreams, scenes, tragedies, and historical events into a seamless whole. It's a tour de force. Read it.

Belongs in any list of the world's great literature

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 27 years ago

A masterpiece to be read on many levels. Told through the eyes of a child, it is a story that gives us a view of how much Albania differs from our Western world, and how much the people there have suffered. At another level it shows Albania not as unique but as an example of the plight of people everywhere