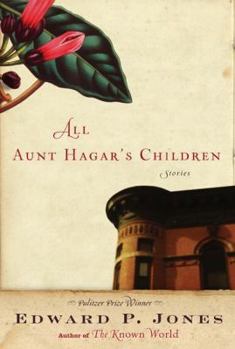

All Aunt Hagar's Children: Stories

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In fourteen sweeping and sublime stories, five of which have been published in The New Yorker, the bestselling and Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Known World shows that his grasp of the human condition is firmer than ever Returning to the city that inspired his first prizewinning book, Lost in the City, Jones has filled this new collection with people who call Washington, D.C., home. Yet it is not the city's power brokers that most...

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0060557567

ISBN13:9780060557560

Release Date:August 2006

Publisher:Amistad Press

Length:416 Pages

Weight:1.55 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.3" x 9.1"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

The Voice of God

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 15 years ago

Jones has such a forgiving, human voice, and these stories are so ever so patient. Never rushed, and never damning.

A unique voice

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

I have read and agree with the other reviews posted thus far and see no need to outline the individual stories (as was well done below). I have a few comments. AN interesting comparison between this collection and Peter Taylor's "The Widows of Thornton" is worth exploring. The latter work, also by a Pulitzer Prize winner of a previous generation (Taylor was a professor at UVA), also deals with family issues that developed as the new South was being created. The widows were the women, left behind by their men of business who ventured forth into the new economy, who wrestled with preserving the values, traditions and social structure of the post-cival war south in the face of a rapidly changing modern world. Like the current work, Taylor's characters often find refuge in the dying home of Thorton TN. Taylor addresses race and socioeconomic issues, but from a white experience. Taylor's prose is very subtle and challenging, like the present work. Relationships change subtly overtime as lives unfold before us in ways that the characters could not forsee. Jones, in addition to dealing with the generations spanning the old home (the deep south) and the new home (Washington, DC), addresses the additional issue of displacement, broken families, crime, drugs, adultery and alienation of an entire race made worse by physical displacement during the great migration. Like Taylor's Tennesee families, Jone's families face new challenges and experience great divides between generations. Whereas Taylor's world is white and well to do, Jones' world is mixed and often delves into the beginings and origins of the underworld that grew in the ghettos of this city that offered hope and bitter dissapointment. Unlike Richard Wright, Jones does not deal mainly in anger. Like Wright, Jones explores alienation in its many forms. The reader is left with little hope for the future as the great strength is rooted in the past and in the south. Many of the stories don't end, per se, but just stop and the characters are left to face an uncertain future. As all good writers, Jones draws the reader in and by identifying with the characters in the stories you experience at a deeper level and beyond words what the author intends to convey. I found many of the stories very dense in that you best not blink or let your mind wander for you can become lost very easily. This is not a simple work of prose. I read and reread many of the stories and was fatigued at times. However, it was a rich and rewarding experience of having been, in some way, part of Jones' world, feeling the complex emotions and living these lives. I must come back to this book some day. Read slowly, and enjoy

clean, aching storytelling from a master...

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

Reviewed by Joanna Pearson for Small Spiral Notebook Since the 2003 publication of his novel The Known World, Edward P. Jones has picked up the occasional award--a MacArthur here, a Pulitzer there--but had there been any doubt about his place in the pantheon, his new book of short stories, All Aunt Hagar's Children, secures it. Taken as a whole, Jones's works (including his 2004 short-story collection Lost in the City) do for 20th-century Washington, D.C., what Joyce's Dubliners did for Dublin: create that city within our literary imaginations. This is not the Washington of bright-faced interns brandishing fresh degrees. Jones's city is a place where African-Americans newly arrived from the rural South grapple with their first experience of urban life in the early 1900's and then continue to make lives for themselves into the mid-twentieth century. Although Jones depicts this time, when certain parts of rural community life still remained intact, with great nostalgia, his characters all struggle within the vast new loneliness of urban life. In the book's the first story, "In the Blink of God's Eye," two newlyweds move to Washington from Virginia: [Aubrey] smiled when he said Ruth's name, and he smiled when he told people he was going to live in Washington, D.C. Ruth had no feeling for Washington. She had generations of family in Virginia, but she was a married woman and had pledged to cling to her husband. And God had the baby in the tree and the story of the wolves in the roads waiting for her. Ruth's fear that wolves roam the D.C. streets seems symptomatic of her new loneliness and vulnerability as a result of her sudden distance from the Virginia family that used to surround her. The baby is a foundling Ruth insists on bringing home, even though the baby's presence threatens her husband, who fears this impenetrable closeness between the woman he married and a child who is not his own. As Ruth's love for this orphaned baby grows and her feelings for her husband weaken, it becomes clear that in this new city, family will come to be defined not as the people you're supposed to love but as the people you actually do love--a change that will affect both Aubrey and Ruth's lives permanently. This story, set as it is in 1901, seems to forecast the new but delicate sort of family life that will evolve as the twentieth century unfolds--the family life of the Washington neighborhood, still steeped in a collective Southernness--that Jones explores in the stories that follow. This is a Washington of old women whom all the neighborhood children call Grandma, and festive Saturdays on H Street; a place where everyone has an aunt in Alabama and Mississippi, and the devil could swim right across the Anacostia River. Even this new urban family, however, will not be completely viable. In the story "A Rich Man," Horace, the seventy-something charmer and flirt of a senior citizens' residence, takes up with a bunch of twenty-something partie

Great

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

The best writers--or at least the most memorable--are the ones who can break the rules of writing and somehow still tell a great story or convince us of something. Jones often changes points of view, shifts time, and fills his stories with a variety of characters. He seems to lack the ability to write a one-dimensional, uninteresting character. Even the one or two stories in the collection that I didn't particularly like left me wanting to read more. And I felt as I read the stories that each was so well wrought and imagined that Jones could easily turn them each into novels. Some readers thought that there were too many characters in Jones' novel _The Known World_, which made it a difficult read. But I found little difficulty reading it. In the short story, however, with its limited space, I think that the large number of characters placed in one story give them little breathing room and make the reading a bit challenging. Sometimes Jones falters, but when he gets the story off the ground right, he soars so high that he can be placed among the best short fiction writers today in the English language. One story, "The Devil Swims Across Anacostia River", despite its provocative title and some amazing passages, I found a little odd and below the quality of the other stories. Stories such as "Old Boys, Old Girls", "A Rich Man", and "Adam Robinson" are truly short masterpieces. I originally read them in the New Yorker. But however many times I read the stories, they continue to amaze me with their elegance. Some characters in this book first appeared in _Lost in the City_, Jones' first collection of short stories. Though some stories in _All Aunt Hagar's Children_ approach perfection, _Lost in the City_ was a far more even work, perhaps because of its consistency of style and genre. _All Aunt Hagar's Children_ contains several stories, such as "The Root Worker" and "A Poor Guatemalan Dreams of a Downtown in Peru" (a very Gabriel Garcia Marquez-esque title), that have magical realist elements. After reading all fourteen stories in this book, I felt a pang of grief, as if I had a finished a good conversation with a friend I knew I would never see again. Read this book. It's simply amazing.

beautiful writing about the real world

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 17 years ago

This collection of stories really has depth and insight. Edward P. Jones writes about the black community in Washington D.C. with great compassion and understanding. There is considerable heartbreak here, but it is presented with such sensitivity and authenticity that it is hard to put down. Jones needs to get some more awards with this one. It is beautifully crafted literary work that deals with the real world.