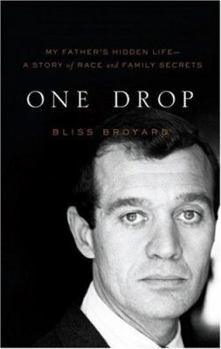

One Drop: My Father's Hidden Life--A Story of Race and Family Secrets

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

In this acclaimed memoir, Bliss Broyard, daughter of the literary critic Anatole Broyard, examines her father's choice to hide his racial identity, and the impact of this revelation on her own life.... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:0316163503

ISBN13:9780316163507

Release Date:September 2007

Publisher:Little Brown and Company

Length:514 Pages

Weight:1.85 lbs.

Dimensions:1.6" x 6.5" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

An awful man

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 6 years ago

This entire book was Bliss trying to make "excuses" for her father, who wabted to be white his entire life, a wife who was in denial of the real race if her children, and a brother who chooses to live as a white man. I've seen this in my own family as I am of the South LA Creole culture! Truly, I wasted my time on this book. I have no sympathy for Anatole Broyard, but I do have empathy with his daughter, Bliss. What he chose to do really threw her for whirlwinds of every kind!!

Bliss Broyard's book on her father

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

This is a wonderful read, especially the first chapter about her father's dying days--very resonant for anyone who has gone through a hospital vigil--with the extra twist of an emerging family secret--her father's true ethnic/racial identity--which leads to much research and this fantastic book. I'm over 150 pages into it--when Etienne Broyard first docks in New Orleans (from Rochelle, France) in the early days of the city. The book is a story of New Orleans, a story of America, a story of a father and daughter relationship, a story of identity, a story of family. Highly recommended.

The Sins of the Father: Race, Identity and Secrets

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

When her mother exposed her father's secret while he was dying in 1990, Bliss Broyard accepted it but was not ready to deal with the complexities of learning her father was of Black heritage. She was not ready when an essay, "The Passing of Anatole Broyard", appeared in Henry Louis Gates' collection, Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man in 1997. When she was finally ready, Broyard wrote a wonderful tribute that is a memoir, a family history, a discourse on race, culture, and identity that is worthy of being a classic. What does a twenty four-year old woman, born and raised in Connecticut with all the trappings of an upper-class WASP environment do when she finds out she is an impostor of sorts? That she is not White...well not according to the one-drop rule that this country imposes. That her father kept a part of him from her, thereby withholding a part of her history? Bliss' reaction and that of her older brother, Todd, was why all the secrecy? Why was it kept from us? Unfortunately, Bliss did not get the answers from her father, Anatole Broyard, the New York Times critic and writer. Thus, she began the journey that would lead her to the truth. That journey took her to meet relatives in New Orleans, Los Angeles and Brooklyn, where she met her aunt Shirley, the sister her father had avoided for most of his adult life. With the help of her newfound family, Bliss began to trace the Broyard family history. But it was the emotional and mental journey about race and identity that would prove to be the most complex. It began with Etienne Broyard of France, Bliss' great-great-great grandfather who came to New Orleans from France in the 1700s. Succeeding generations included mixed-race women of African heritage or mixed-race and Free People of Color also known as Gens de Libre Coleur. The majority of the family had a "white looking appearance" and at different times, passed for White, most often for economic reasons. Economic reasons were the main reason Anatole's parents, Paul and Edna, passé blanc when they moved from New Orleans to Brooklyn, New York in the 1920s when he was six years old. In order to secure employment as a carpenter, Paul became White in the daytime. When Anatole started college he slowly began his journey of subterfuge. To understand Bliss' angst and confusion about where she fit on the color line, one must first understand the dynamics of the Creole of Color culture and the convoluted caste system of Louisiana. The three-tier racial categorization; White, Black, and Creole/mixed race was an accepted practice. But as no race or culture is a monolith, there are different feelings among Creoles about identity today. Some Creoles have assimilated either into the white culture intermarrying/mixing/bleaching until the African blood is obliterated, while others have assimilated into the African American community and identify as Black. Bliss' family fell into both categories as well as those who held themselves separate and v

Personal Observations on Bliss Broyard's One Drop

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

Personal Observations on Bliss Broyard's One Drop: My Father's Hidden Life--A Story of Race and Family Secrets (New York: Little, Brown and Co., 2007) Let me say right off that we at Backintyme Publishing enjoyed the book and recommend it without reservation. But do not be fooled by the misleading marketing blurb (more about this later); One Drop is not a book about a White woman who suddenly discovers that she is "really" Black. It is not about Bliss Broyard's father. It is not even about her search for her father's roots among the Louisiana Creoles. The book introspects Ms. Broyard's feelings about what she found while searching for those roots. Anatole Broyard died in 1990 after an illustrious career as literary critic for the New York Times. He was one of the intellectual beacons of the U.S. twentieth century. Six years after his death, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., head of Black Studies at Harvard, published an essay "outing" the late Broyard as a Black man who had lived a lie by pretending to be White all his professional life. According to Bliss, she and her older brother Todd only learned about their father's Colored Creole ancestry shortly before his death when she was twenty-four. Apparently, it then took her over a decade to assemble the facts to refute Gates's racialist ignorance. I lay my cards on the table. I am not objective about U.S. racialism. I am of a culture that is as proud of its African ancestry as of its European and Native American roots. (By coincidence, I happen to have the same fraction of sub-Saharan genetic admixture as Bliss.) I feel as at home among Creoles, Melungeons, Redbones, and Seminoles as I do among my own Puerto Rican people. I love seeing siblings accepted as routine, whom the newspapers would breathlessly report as "one chance in a million." But, like Anatole Broyard, I am not African-American, and I will dispute anyone who ignores my culture and accuses me of betraying my "race" merely because my genome is typical of New World inhabitants, as Gates did to Broyard after his death. The overt villain of this book is Gates and he is essential to its existence. Had Gates never accused Broyard's corpse of being a race traitor, this book about Bliss's genealogical quest could not have been published. Had Gates never advised Bliss's mother that "the best thing she could do was to help [Bliss] accept her blackness," Bliss might not have resolved to learn the truth. Had Gates not suggested that they petition Connecticut to alter Bliss's birth certificate to show "black" ancestry, he might have seemed rational. As it is, you conclude that Gates is delusional--an honest believer in the false dichotomy of the U.S. color line: if you are not White, then you must be Black, like it or not. He apparently wants to infect others with his foolishness that any African ancestry makes you INVOLUNTARILY Black.* In short, we should all be grateful to Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Without him, this excellent book would probably no

Brilliant, unblinking, and kind -- I couldn't put it down

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 16 years ago

I read this book in three sittings -- plus two middle of the night wakings up where I read for hours more. Not only is it wonderfully written, but Bliss Broyard is willing to turn over all the stones and gems she finds, and look directly at what she sees. Like A.M. Homes, and Tobias Wolff, Broyard has a clear-eyed willingness to review the past and to experience new things while still remaining a thinking, sensitive person. She doesn't compromise or lose herself despite the demands of others. Instead she grows and lets us grow along with her. The creole experience in New Orleans is unique in American race relations. It takes time and an open mind and heart to explore the world of the free people of color in the French colonies. Much of this history doesn't overlap with the experiences of others from the African diaspora. We learn about the horrors of the Middle Passage slave trade in school and through film, but a first introduction to the creole world, especially after learning it is your own ancestral world, can be astonishing. This book is not only a personal journey, but a wonderful introduction to the rich and ongoing history of creoles in the United States. I cannot recommend One Drop more highly.