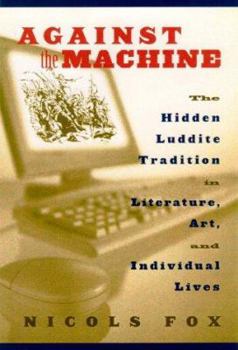

Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite Tradition in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives

Select Format

Select Condition

Book Overview

From the cars we drive to the instant messages we receive, from debate about genetically modified foods to astonishing strides in cloning, robotics, and nanotechnology, it would be hard to deny... This description may be from another edition of this product.

Format:Hardcover

Language:English

ISBN:1559638605

ISBN13:9781559638609

Release Date:October 2002

Publisher:Island Press

Length:240 Pages

Weight:1.72 lbs.

Dimensions:1.3" x 6.3" x 9.3"

Customer Reviews

5 ratings

Thank you Nicols Fox.

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

It can be intimidating to venture into anti-machine literature. If you've been postponing the plunge, this is the book for you. Fox is not trying to scare you. She walks along with you through the odd turns history makes at times. Apparently people never wanted to work in factories. They did not want machines to dominate. They did not even want clocks. Fox's book is a well-researched, readable introduction to an important topic. You won't be sorry.

Against the Machine

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 14 years ago

Near the end of her book, the author writes: "Some anarchists are Luddites, but the original Luddites were not anarchists. They eventually were forced into violent expression of their frustration, but it was not their intention to bring down a system. Rather, it was to protect a system that existed and was working -- if not perfectly, then very much better than what was being introduced to replace it." (333-34) Concerning each person discussed in this book (I do not mention names), the question then needs to be asked: Is this person hoping to protect a system that is under threat by recent changes or to recover a system recently lost, or is he hoping to bring down a system and replace it with something else entirely, either a system new and unprecedented or perhaps one long ago lost; and what role does technology play in this? Additionally, to what does the term 'technology' refer? Do they all agree on the referent of the term? The author's unsystematic approach leaves some of these questions unanswered, and in most cases unasked. Entrances to an anti-technology viewpoint are many. The book introduces some of them. Here are a few. (I've compressed them as much as seemed fair, and offer no lines of reasoning, either fallacious or logical, to support them. The book's presentation is not as abstract or explicit.) Deep within the notion of morality is the undertone that asceticism is the purest form of morality, and that self-sacrifice, self-denial, and abstinence are always morally pure and so always better choices than self-interest, egocentrism, or self-indulgence. In essence, you are never of the first importance. Because this undertone is always present and quietly implicit in the notion of morality, it can become, for some people, loudly explicit when the issue of getting along with less is raised. "Modern conveniences" (including, but necessarily not limited to, devices and machines designed by mechanical or electrical engineers based upon principles discovered by science) start to look to some people like temptations to immorality, or at least to a less moral life. The primitive life seems to them the morally authentic life. This is one entrance into an anti-technology viewpoint. It is also, by expansion, an entrance into an anti-science viewpoint, which shows up in this book quite often. Another issue is the need for money, and the need to work to get that money. The more you want to buy, the more money you need and the more money you need the more you need to work and think about work, and thus the more your life becomes about the work you do to get the money you need to buy the things you want. This used to be called the "rat race". Wanting less, living with less, cutting down your expenses and economic obligations, might free up your life a little so you can live less for your job and more for yourself and for those with whom you live. This is another entrance into an anti-technology viewpoint. It is also, by expansion, an entrance i

A Great Insight Into The Control Modern Life Has Over Us

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 19 years ago

Nicols Fox has pinpointed so many key items as to why modern life can be so frustrating for so many of us, and why it is so difficult for us to understand the reasons why. One main reason is that the history of the 'machine control' goes back way before our own lifetimes, and so we are often unaware of what life might be like without that degree of machine control we all currently live with. The roots go back to the start of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, where over-rationalised 'reason' and 'calculation' started to assume an increasing degree of respectability over moral values. The moral premise that just because you are powerful or 'able' to do something, you should not necessarily actually do it, effectively went out of the window. Children were sent down coal mines and were made to work in factories for 16 hours a day, and so on. It took Acts of Parliament to eventually outlaw such extreme examples of control, but the overwhelming force to treat people simply as calculated units of production continued. We see the machine operating in everyday life today, where so-called "restaurants" (some fast-food joints) are more similar to factories, and where the staff have their hand movements calculated down to the 1/10th of a second and their words exchanged with customers often have to come from a script. Human input is no longer required by so many workers, simply the mechanistic following of prescribed steps to the nth degree, a wholly dehumanising process. This dehumanisation of people can lead to frustration, anger, or even violence, with people really not understanding why. It also leads to a society where people as consumers have become totally dependent or "addicted" to factory-made items which their parents used to produce themselves. Home cooking is a great example, where on Thanksgiving Day in the US Emergency 'Hot Lines' are set up on TV channels for people who still feel the need to cook a turkey and celebrate their tradition, but who have absolutely no idea how to do it any more. Calls come from people who have put a totally frozen 14lb turkey, still in its shrink wrap in the oven at 500 degF, and are wondering if that was the right thing to do. The reason being is that modern TV dinners and junk food have taken away people's need to practice the basic human skill and have the dignity of cooking their own meals. So many have become dependent on "ordering-in" a pizza every night, or microwaving pre-packaged food, never even knowing how a vegetable grows or where chickens come from. In short people have become addicted and dependent on technologies which take their money, in a similar way as with drugs, just less extreme, with little or no knowledge or vison of how to become 'undependent' and have the freedom to choose whether to buy the factory-made product, or not. I think this book 'Against the Machine' by Nicols Fox is a fantastic contribution to a vision of human freedom where people can make better

Against the Machine by Nicols Fox

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

As I read "Against the Machine: The Hidden Luddite Tradition in Literature, Art and Individual Lives" by Nicols Fox, I was aware of an interesting paradox. In its essence, "Against the Machine" charts the rise of the machine from the Industrial Revolution to the present and explores the resistance of workers (the original Luddites), writers, artists, and thinkers to this development. While attempting to be fair minded (and, for the most part, succeeding), Ms. Fox asks whether we have lost more than we have gained. For years, I have wondered the same thing, and I found myself in complete sympathy with Ms. Fox. Yet without machines, and their father-technology-"Against the Machine" would not exist. From its subject matter to its actual physical state-that is, of being a book-"Against the Machine" is totally dependent on machines.What's a neo-Luddite to do? One option is to buy an island off the coast of Maine, build a small cabin, and live as simply as possible with no electricity, telephone, or central heating. In the first chapter of "Against the Machine," Ms. Fox writes of Nan and Arthur Kellam, who did that very thing. As Nan put it, "[they wanted] to leave behind the battle for non-essentials and the burden of abundance to build in the beauty of this million-masted island a simple home and an uncluttered life." And this they did for forty years. The story ends sadly. Arthur dies, and Nan becomes ill and has to leave their beloved island. Yet, isn't that how all stories inevitably end? No one lasts forever. In the meantime, Nan and Arthur Kellam lived lightly and simply and deliberately.What modern-day commuter, racing between work, home, errands, and children, hasn't longed for at least some measure of the Kellams' peaceful lives? But, alas, there aren't enough islands for everyone, and most of us must resign ourselves to lives that fall short of such romantic tranquility. However, that doesn't mean we have to concede defeat and use machines mindlessly. And more importantly, we can consider the questions that Ms. Fox asks, "what, after all, is technology? Is it a simple screw? Is it the wheel? Is it a printing press? Is it nuclear fission? ...To think seriously about technology, it will be necessary to examine the nature of mechanical innovation..."Ms. Fox does this with a vengeance. After the idyllic first chapter with the Kellams, Ms. Fox plunges us into the heart of manufacturing England in the 1800s and chronicles the struggles between the factory owners and the workers. Almost from the start, the story is ugly, with the owners obsessed with profits and quotas while the workers desperately try to maintain standards and not become obsolete. Downsized was not a term that was used back then, but with each mechanical innovation, the workers felt it keenly, even if they didn't know the word.Ned Ludd, or King Ludd, a figure who was perhaps a blend of myth and reality, became the symbol around which the workers rallied, and in the end, gave them

Against the machine connects the dots

Published by Thriftbooks.com User , 21 years ago

Always harbored some suspicion about the "march of technology?"The author of Against the Machine, The Hidden Luddite Tradition in Literature, Art, and Individual Lives, wants to share with you the reason why.Bass Harbor, Maine author Nicols Fox, who shocked the nation and the world with revelations on bacterial contamination in processed food in her expose, "Spoiled," begins with the social forces that prompted Ned Ludd and his followers to take up arms and traces humanity's love-hate relationship with technology across the next two centuries. Along the way she discovers a deep and broad suspicion about mechanization, industrialization and globalization that permeates art, literature, and politics. As she points out there are many among us who worry, as writer and naturalist Henry David Thoreau said, we are becoming "tools of our tools."While for some people the premise of this book might make an interesting outline for a lengthy magazine piece, such as those in the Economist for which Ms. Fox frequently writes, she has taken it to the next level and beyond. She has conducted exhaustive research and a broad range of reading to weave together an impressive text that carries the thread of Luddism from those first violent clashes in the early 1800s, through the writings and works of famous artists such as William Blake, Rachael Carson, Edward Abbey, E.B. White, Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, David Brower, Edouard Manet, Charlie Chaplin, William Morris and John Muir.Along the way Ms. Fox brilliantly manages to tap into the repressed fears harbored by many modern people who feel disconnected while daily using technology, which we seldom understand and tends to isolate us and remove us further and further from the earth, the weather, each other, and, in the end, our own humanity.And, Ms. Fox, who, in an ironic twist, operates a Luddite bookstore on the Internet, shows us that the push to preserve the natural world is also another manifestation of Luddite philosophy. "Preserving American's wild land against the utilitarian view and its conjoined twin, economic reality, is the same battle the Luddites fought," Ms. Fox writes. She also helps dispel some common stereotypes that those that eschew modernity, such as the Unabomber, tend to live reclusively or hate society. "Some anarchists are Luddites but the original Luddites were not anarchists," she writes. "They eventually were forced into a violent expression of their frustration but it was not their intention to bring down the system."Throughout "Against the Machine," Ms. Fox illustrates her points with vignettes from Maine where, she points out, Luddism is alive and well.She devotes her first chapter to Art and Nan Kellam's cabin on Placentia Island off Tremont, gives considerable space to Scott and Helen Nearing and also peoples her book with other familiar names and faces including Robert and Diane Phipps of Bar Harbor and Bill Coperthwait, "the yurt guy."As technology continues to clog our lives, fr